NÚMEROS COMPLEXOS

1. Definições

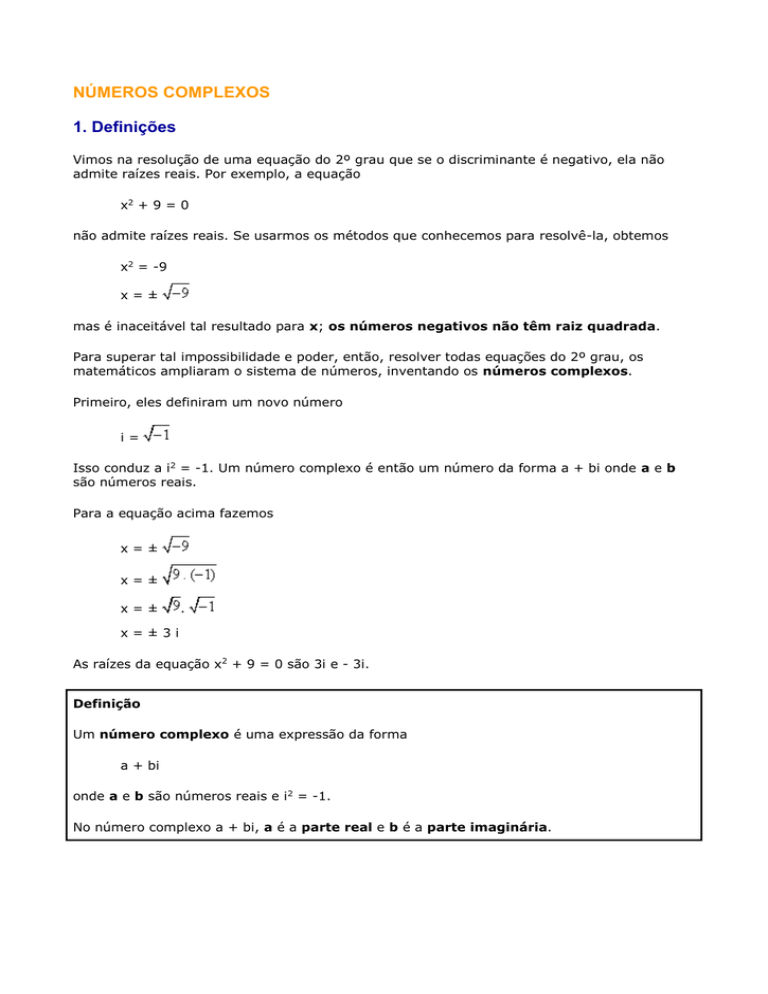

Vimos na resolução de uma equação do 2º grau que se o discriminante é negativo, ela não

admite raízes reais. Por exemplo, a equação

x2 + 9 = 0

não admite raízes reais. Se usarmos os métodos que conhecemos para resolvê-la, obtemos

x2 = -9

x=±

mas é inaceitável tal resultado para x; os números negativos não têm raiz quadrada.

Para superar tal impossibilidade e poder, então, resolver todas equações do 2º grau, os

matemáticos ampliaram o sistema de números, inventando os números complexos.

Primeiro, eles definiram um novo número

i=

Isso conduz a i2 = -1. Um número complexo é então um número da forma a + bi onde a e b

são números reais.

Para a equação acima fazemos

x=±

x=±

x=±

.

x=±3i

As raízes da equação x2 + 9 = 0 são 3i e - 3i.

Definição

Um número complexo é uma expressão da forma

a + bi

onde a e b são números reais e i2 = -1.

No número complexo a + bi, a é a parte real e b é a parte imaginária.

Exemplos

2 + 5i

i

parte real 2

parte imaginária 5

parte real

parte imaginária

12i

parte real 0

parte imaginária 12

-9

parte real -9

parte imaginária 0

Um número como 12i, com parte real 0, chama-se número imaginário puro. Um número

real como -9, pode ser considerado como um número complexo com parte imaginária 0.

Igualdade de números complexos

Os números complexos a + bi e c + di são iguais se suas partes reais são iguais e suas partes

imaginárias são iguais, isto é:

a + bi = c + di se

Exemplos

2 + 5i =

Se x e y são números reais e x + yi = 7 - 4i, então x = 7 e y = - 4.

Fonte: http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_1.html

2. Aritmética dos números complexos

Adição e Subtração

Adição

(a + bi) + (c + di) = (a + c) + (b + d)i Para adicionarmos dois números

complexos, adicionamos as partes

reais e as partes imaginárias

Subtração

(a + bi) - (c + di) = (a – c) + (b – d)i Para subtrairmos dois números

complexos, subtraímos as partes

reais e as partes imaginárias

Exemplos

(3 + 4i) + (- 7 + 8i) = (3 - 7) + (4 + 8) i

= - 4 + 12i

Na prática, fazemos

(3 + 4i) + (-7 + 8i) =

(- 5 + 6i) - (4 - 2i) = (- 5 - 4) + [6 - (- 2)] i

= - 9 + 8i

Na prática fazemos

(-5 + 6i)

Multiplicação

(a + bi) . (c + di) = (ac – bd) + (ad + bc)i Multiplicamos números

complexos como multiplicamos

binômios, usando i2 = - 1

Exemplos

Distributiva

= 6 – 8i + 9i – 12i

2

= 6 + i – 12 . (-1) -8i + 9i = i e i2 = - 1

= 6 + i + 12

= 18 + i

Distributiva

= – 8 – 4i + 4i + 2i

2

= – 8 + 2 . (-1) -4i + 4i = 0 e i2 = - 1

= –8–2

= – 10

= – 3i . (4) – 3i . (-2i)

= - 12i + 6i2

= - 12i + 6 . (-1)

= - 6 - 12i

Fonte:

http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_2.html

3. O conjugado e a divisão

Divisão de números complexos é semelhante à racionalização do denominador de uma fração

com radicais. Assim, se temos o quociente

nosso objetivo é escrevê-lo na forma a + bi.

Para isso, introduziremos inicialmente o conceito de conjugado de um número complexo.

Complexos conjugados

O conjugado de um número complexo a + bi é a - bi, e o conjugado de a - bi é a + bi.

Os números complexos a + bi e a - bi são chamados complexos conjugados.

Para um número complexo z, seu conjugado é representado com ; então, se z = a + bi

escrevemos = a - bi.

Exemplos

O conjugado de z = 2 + 3i é = 2 - 3i

O conjugado de z = 2 - i é = 2 + 3i

O conjugado de z = 5i é = - 5i

O conjugado de z = 10 é = 10

Quando multiplicamos um número complexo z = a + bi pelo seu conjugado = a - bi, o

resultado que se obtém é um número real não negativo:

z.

= (a + bi) . (a – bi)

= a2 – abi + abi – b2i2

= a2 – b2 . (-1)

= a2 + b2

A soma dos quadrados

de dois números reais

nunca é negativa

Usamos essa propriedade para expressar o quociente de dois números complexos na forma a

+ bi.

Dividindo dois números complexos

Para escrevermos o quociente

na forma A + Bi, multiplicamos o numerador e o

denominador pelo conjugado do denominador.

Exemplo

Vamos escrever o quociente

na forma a + bi.

Multiplicamos o numerador e o denominador pelo conjugado do denominador, para

obter um número real no denominador.

=

=

=

=

i

=1–i

Fonte:

http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_3.html

4. Potências de i

Temos:

i0 = 1

i4 = i2 . i2 = (-1) . (-1) = 1

i1 = i

i5 = i4 . i = 1 . i = i

i2 = -1

i6 = i4 . i2 = 1 . (-1) = -1

i3 = i2 . i = -1 . i = -i

i7 = i4 . i3 = 1 (-i) = -i

Observe que as quatro potências de i na coluna da esquerda, repetem-se nos quatro casos

seguintes na coluna da direita. Este ciclo

1, i, -1, -i

repete-se indefinidamente.

Então, para simplificar ix para x > 4, buscamos o maior múltiplo de 4 contido em x; por

exemplo

i26 = i24 . i2 = (i4)6 . i2

= 16 . (-1)

= -1

i43 = i40 . i3 = (i4)10 . i3

= i10 . (-i)

= -i

Fonte:

http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_4.html

5. O caso da raiz quadrada

Sabemos que um número real positivo r tem duas raízes quadradas

e-

,

Os números reais negativos também tem duas raízes quadradas. Por exemplo, 2i e - 2i são as

raízes quadradas de - 4 porque

(2i)2 = 22 . i2 = 4 . (-1) = - 4

(- 2i)2 = (- 2)2 . i2 = (- 2)2 . i2 = 4 . (- 1) = - 4

De um modo mais geral, se r > 0 é um número real, o número real negativo - r, tem duas

raízes quadradas, porque

(i

(-i

)2 = i 2 . (

)2 = -1 . r = -r

) = (-1) 2 . i2 . (

2

Chamamos i

)2 = 1 . (-1) . r = -r

de raiz quadrada principal de - r, e usamos o desenho

para representá-

la; a outra raiz quadrada - i

é representada com . Note que as duas raízes quadradas

são números complexos imaginários puros, e que são conjugados.

Raízes quadradas de números negativos

Se - r < 0, então as raízes quadradas de - r são

i

e-i

A raiz quadrada principal de - r é i

=i

Exemplos

:

=i

=i

=i

= 5i

=i

Observação

Devemos ter especial cuidado quando efetuamos operações envolvendo raízes

quadradas de números negativos. Quando a e b são positivos vale a propriedade

.

=

. Mas, quando ambos são negativos a propriedade não é verdadeira. Por

exemplo, a definição dada permite-nos escrever

.

= i2 .

=i

.i

.

=

Entretanto, se usarmos a propriedade temos

.

=

Quando multiplicamos radicais de números negativos, devemos em primeiro lugar,

escrevê-los na forma i

, com r > 0.

Fonte:

http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_5.html

6. Representação dos números complexos

Um número complexo é constituído por duas componentes: a parte real e a parte

imaginária. Isso sugere a utilização de dois eixos para representá-lo: um para a parte real e

o outro para a parte imaginária. Esses dois eixos chamam-se eixo real e eixo imaginário,

respectivamente. O plano determinado por esses dois eixos chama-se plano complexo.

Para desenharmos o gráfico do número complexo a + bi, marcamos o ponto (a; b) no plano.

Exemplo

Fonte:

http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_6.html

7. Módulo de número complexo

O módulo (ou valor absoluto) do número complexo a + bi é distância de a + bi à origem do

plano complexo. Usando o Teorema de Pitágoras, concluímos que a distância de (a; b) a (0;

0) é

.

Definição

O módulo (ou valor absoluto) do complexo z = a + bi é

|z|=

Exemplos

O módulo do número complexo - 3 + 4i é

|-3 + 4i| =

=

=5

O módulo do número complexo 7 + 4i é

|7 + 4i| =

=

Fonte: http://www.10emtudo.com.br/demo/matematica/numeros_complexos/index_7.html

---------------------------

Complex Numbers: Introduction (page 1 of 3)

Sections: Introduction, Operations with complexes, The Quadratic Formula

Up until now, you've been told that you can't take the square root of a negative number. That's because you

had no numbers that, when squared, were negative. Every number was positive after you squared it. So you

couldn't very well square-root a negative and expect to come up with anything sensible.

Now, however, you can take the square root of a negative number, but it involves using a new number to do

it. This new number was invented (discovered?) around the time of the Reformation. At this time, nobody

believed that any "real world" use would be found for this new number, other than easing the computations

involved in solving certain equations, so the new number was viewed as being a pretend number invented

for convenience sake.

(But then, when you think about it, aren't all numbers inventions? It's not like numbers grow on trees! They

live in our heads. We made them all up! Why not invent a new one, as long as it works okay with what we

already have?)

Anyway, this new number is called "i", standing for "imaginary", because "everybody knew" that i wasn't

"real". (That's why you couldn't take the square root of a negative number before: you only had "real"

numbers; that is, numbers without the "i" in them.) The imaginary is defined to be:

Then:

Copyright © Elizabeth Stapel 2006-2008 All Rights Reserved

Now, you may think you can do this:

But this doesn't make any sense! You already have two numbers that square to 1; namely –1 and +1. And i

already squares to –1. So it's not reasonable that i would also square to 1. This points out an important

detail: When dealing with imaginaries, you gain something (the ability to deal with negatives inside square

roots), but you also lose something (some of the flexibility and convenient rules you used to have when

dealing with square roots). In particular, YOU MUST ALWAYS DO THE i-PART FIRST!

Simplify sqrt(–9).

(Note: This is "

", not "

Simplify sqrt(–25).

Simplify sqrt(–18).

Simplify –sqrt(–6).

". The i is outside the radical!)

In computations, you deal with i just as you would with x, except for the fact that x2 is just x2, but

i2 is –1:

Simplify 2i

+ 3i.

2i + 3i = (2 + 3)i = 5i

Simplify 16i

– 5i.

16i – 5i = (16 – 5)i = 11i

Multiply and simplify (3i)(4i).

(3i)(4i) = (3·4)(i·i) = (12)(i2) = (12)(–1) = –12

Multiply and simplify (i)(2i)(–3i).

(i)(2i)(–3i) = (2 · –3)(i · i · i) = (–6)(i2 · i)

=(–6)(–1 · i) = (–6)(–i) = 6i

Note this last problem. Within it, you can see that

, because i2 = –1. Continuing, you get:

This is a cycle:

In other words, to calculate any high power of i, you can convert it to a lower power by taking the closest

multiple of 4 that's no bigger than the exponent and subtracting this multiple from the exponent. For example,

a common trick question on tests is something along the lines of "Simplify i99", the idea being that you'll try to

multiply i ninety-nine times and you'll run out of time, and the teachers will get a good giggle at your expense

in the faculty lounge. Here's how the shortcut works:

i99 = i96+3 = i(4×24)+3 = i3 = –i

That is, i99 = i3, because you can just lop off the i96. (Ninety-six is a multiple of four, so i96 is just 1, which you

can ignore.) In other words, you can divide the exponent by 4 (using long division), discard the answer, and

use only the remainder. This will give you the part of the exponent that you care above. Here are a few more

examples:

Simplify i17.

i17 = i16 + 1 = i4 · 4 + 1 = i1 = i

Simplify i120.

i120 = i4 · 30 = i4· 30 + 0 = i0 = 1

Simplify i64,002.

i64,002 = i64,000 + 2 = i4 · 16,000 + 2 = i2 = –1

Now you've seen how imaginaries work; it's time to move on to complex numbers. "Complex" numbers have

two parts, a "real" part (being any "real" number that you're used to dealing with) and an "imaginary" part

(being any number with an "i" in it). The "standard" format for complex numbers is "a + bi"; that is, real-part

first and i-part last.

Fonte: http://www.purplemath.com/modules/complex.htm

Operations on Complex Numbers (page 2 of 3)

Sections: Introduction, Operations with complexes, The Quadratic Formula

Complex numbers are "binomials" of a sort, and are added, subtracted, and multiplied in a similar way.

(Division, which is further down the page, is a bit different.)

Simplify (2

+ 3i) + (1 – 6i).

(2 + 3i) + (1 – 6i) = (2 + 1) + (3i – 6i) = 3 + (–3i) = 3 – 3i

Simplify (5 –

2i) – (–4 – i).

(5 – 2i) – (–4 – i)

= (5 – (–4)) + (–2i – (–i)) = (5 + 4) + (–2i + i)

= (9) + (–1i) = 9 – i

Simplify (2 –

i)(3 + 4i).

(2 – i)(3 + 4i) = (2)(3) + (2)(4i) + (–i)(3) + (–i)(4i)

= 6 + 8i – 3i – 4i2 = 6 + 5i – 4(–1)

= 6 + 5i + 4 = 10 + 5i

For this last example, if you learned "FOIL", FOILing works for this kind of multiplication. But whatever

method you use, remember that multiplying and adding with complexes works just like multiplying and

adding polynomials, except that, while x2 is just x2, i2 is –1. That is, you can use the exact same techniques

for simplifying complex-number expressions, but you can simplify even further with complexes than with

polynomials, because i2 reduces to the number –1.

Adding and multiplying complexes isn't too bad. It's when you start on fractions (that is, division) that things

turn ugly. Most of the reason for this ugliness is actually arbitrary. Remember back in elementary school,

when you first learned fractions? Your teacher would get her panties in a wad if you used "improper"

fractions. For instance, you couldn't say " 3/2 "; you had to convert it to "1 1/2". But now that you're in

algebra, nobody cares, and you've probably noticed that "improper" fractions are often more useful than

"mixed" fractions. The problem in the case of complexes is that your professor will get his boxers in a bunch

if you leave imaginaries in the denominator. So how do you handle this?

Suppose you have the following problem:

Simplify

The point here is that they want you to get rid of the i underneath. The 2 is fine, but the i has got to

go. To do this, you use the fact that i2 = –1. If you multiply top and bottom by i, then the i underneath

will vanish in a puff of negativity:

So the answer is –( 3/2 )i.

This was simple enough, but what if you have something more complicated?

Simplify

If you multiply top and bottom by i, you get:

Since you still have an i underneath, this didn't help much. So how do you handle this simplification?

You use something called "conjugates". The conjugate of a complex number a + bi is the same

number, but with the opposite sign in the middle: a – bi. When you multiply conjugates, you are, in

effect, multiplying to a difference of squares:

Note that the i's disappeared. This is what the conjugate, difference-of-squares thing is for. Here's

how it is used: Copyright © Elizabeth Stapel 2006-2008 All Rights Reserved

So the answer is 6/5 – ( 3/5)i.

In the last step, note how the fraction was split into two pieces. This is because, technically speaking, a

complex number is in two parts, the real part and the i part. They aren't supposed to "share" the

denominator.

Fonte: http://www.purplemath.com/modules/complex2.htm

Complex Numbers & The Quadratic Formula (page 3 of 3)

Sections: Introduction, Operations with complexes, The Quadratic Formula

You'll probably only use complexes in the context of solving quadratics for their zeroes. (There are many other practical uses

for complexes, but you'll have to wait for more interesting classes like "Engineering 201" to get to the "good stuff".)

Remember that the Quadratic Formula solves "ax2 + bx + c = 0" for the values of x. Also remember that this means that

you are trying to find the x-intercepts of the graph. When the Formula gives you a negative inside the square root, you can now

simplify the zero by using complex numbers. The answer you come up with is a valid "zero" or "root" or "solution" for "ax2 + bx

+ c = 0", because, if you plug it back into the quadratic, you'll get zero after you simplify. but you cannot graph a complex

number on the x,y-plane. So this "solution to the equation" is not an x-intercept. In other words, you can make this connection

between the Quadratic Formula, complex numbers, and graphing:

x2 – 2x – 3

a positive number inside

the square root

two real solutions

two distinct x-intercepts

x2 – 6x + 9

zero inside the square

root

one (repeated) real

solution

one (repeated) xintercept

x2 + 3x + 3

a negative number

inside the square root

two complex solutions

no x-intercepts

As an aside, you can graph complexes, but not in the x,y-plane. You need the "complex" plane. For the complex plane, the xaxis is where you plot the real part, and the y-axis is where you graph the imaginary part. For instance, for the complex number

3 – 2i, you would graph it like this:

This leads to an interesting fact: When you learned about regular ("real") numbers, you also learned about their order (this is

what you show on the number line). But x,y-points don't come in any particular order. You can't say that one point "comes

after" another point in the same way that you can say that one number comes after another number. For instance, you can't

say that (4, 5) "comes after" (4, 3)" in the way that you can say that 5 comes after 3. Pretty much all you can do is compare

"size", and, for complex numbers, "size" means "how far from the origin". To do this, you use the Distance Formula, and

compare which complexes are closer to or further from the origin. This "size" concept is called "the modulus". For instance,

looking at our complex number plotted above, its modulus is computed by using the Distance Formula: Copyright © Elizabeth Stapel

2006-2008 All Rights Reserved

Note that all points at this distance from the origin have the same modulus. All the points on the circle with radius sqrt(13) are

viewed as being complex numbers having the same "size" as 3 – 2i.

Fonte: http://www.purplemath.com/modules/complex3.htm