Introdução

Homeostase e

termorregulação

Daniel Oliveira Mesquita

Introdução

O que é homeostase?

Em qualquer ser vivo, milhares de reações

ocorrem a cada segundo

Essas reações necessitam de um meio

aquoso

1

3

PART | III Physiological Ecology

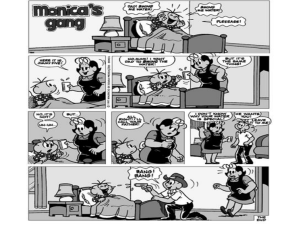

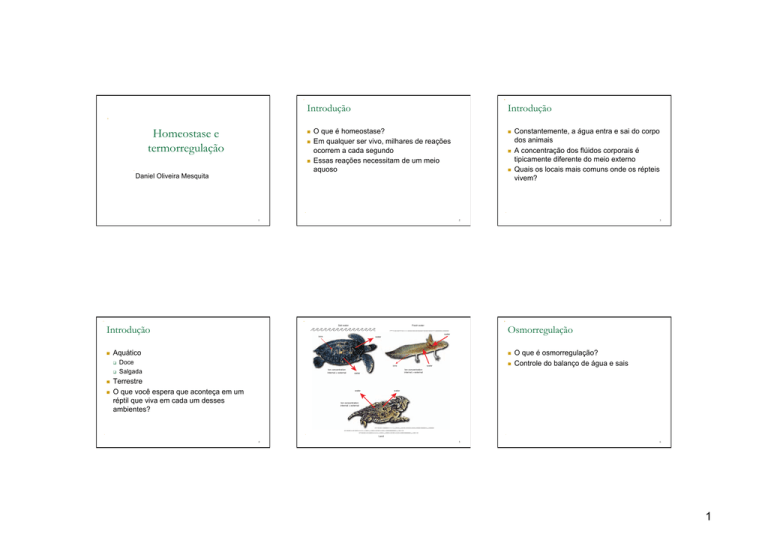

Salt water

Osmorregulação

Fresh water

water

ions

water

Aquático

Doce

Salgada

ions

Ion concentration

Internal < external

Terrestre

O que você espera que aconteça em um

réptil que viva em cada um desses

ambientes?

Constantemente, a água entra e sai do corpo

dos animais

A concentração dos flúidos corporais é

tipicamente diferente do meio externo

Quais os locais mais comuns onde os répteis

vivem?

2

170

Introdução

water

O que é osmorregulação?

Controle do balanço de água e sais

Ion concentration

internal > external

water

water

water

Ion concentration

internal > external

Land

4

FIGURE 6.1 Osmotic challenges of amphibians and reptiles in saltwater, freshwater, and on land. In saltwater,

the animal is hyposmotic compared to its environment, and because its internal ion concentration is less than that

of the surrounding environment (internal < external), water moves outward. In freshwater, the animal is hyperosmotic to its environment, and the greater internal ion concentration (internal > external) causes water to move

inward. On land, the animal is a container of water and ions, but because the animal is not in an aqueous environment, internal fluctuations in ionic balance result from water loss to the relatively drier environment. The animal actually has much higher ion concentrations (internal > external) than surrounding air, and if ionic

concentrations reach high levels, as they do in some desert reptiles, ion transfer can occur via salt glands, usually

in the nasal or lacrimal region.

Metabolic by-products and water diffuse into the kidney

tubules from the circulatory system via the glomeruli,

where capillaries interdigitate with the kidney tubules. In

the proximal tubules, glucose, amino acids, Na+, Cl-, and

water are resorbed. Nitrogenous waste products and other

ions are retained in the urine, and additional water and

Na+ are removed in the distal tubules. In amphibians,

due to a high filtration rate, about one-half of the primary

filtrate enters the bladder even though more than 99% of

filtered ions have been resorbed. As a consequence, urine

produced by most amphibians is dilute. Some striking

exceptions include African reedfrogs (Hyperolius), which

exhibit increased levels of urea in plasma during dry

periods, and the frogs Phyllomedusa and Chiromantis,

which are uricotelic.

In reptiles, the filtration rate is lower than that of

amphibians, and resorption of solutes and water is

greater. Between 30 and 50% of water that enters the

glomeruli of reptiles is resorbed in the proximal tubules

alone. Urine generally empties into the large intestine

in reptiles, but some have urinary bladders. In all cases,

whether amphibian or reptile, urine flows from the urinary ducts into the cloaca and then into the bladder or

the large intestine. Additional absorption of Na+ by

active transport can occur in some freshwater reptiles

from water in the bladder. Most reptiles produce

5

6

1

Osmorregulação

Osmorregulação

Muitas estruturas estão envolvidas com a

osmorregulação

Pele

Trato digestivo

Rins

Bexiga

Osmorregulação

Em água doce, os répteis são hiperosmóticos

Em água salgada, hiposmóticos

Qual é a tendência natural?

Hidratação excessiva

Íons tornam-se muito diluídos

A permeabilidade da pele deve diminuir

Eliminação de água deve aumentar

8

9

Balanço de água e sais

Em água salgada, a água tende a sair do

organismo desses animais

Osmorregulação

Em água doce, a água tende a entrar no

organismo desses animais

7

Desidratação excessiva

Íons tornan-se muito concentrados

Eles perdem água principalmente pela

evaporação

Controlam esse problema de maneira

semelhante às espécies marinhas

A permeabilidade da pele deve diminuir

Eliminação de água deve diminuir

Como deve acontecer em animais terrestres?

10

70 - 80% de água em seus corpos

Como esses animais vivem em uma grande

variedade de ambientes

11

Vários íons estão dissolvidos

Na, Mg, Ca, K são essenciais

Uma série de mecanismos são necessários para

a manutenção do balanço osmótico

12

2

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Ganho

Comida

Bebida

Tegumento

Metabolismo

Perda

Excreção

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Fezes

Urina

Glândulas de sal

Respiração

Tegumento

Os répteis trocam pouca água pela pele

A ato de beber água é uma importante fonte

deste produto

Alguns lagartos do deserto (e.g., Xantusia

vigilis e Coleonyx variegatus) bebem água

que condensa sobre sua pele

Xantusia vigilis

13

14

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Tartarugas (África do Sul) coletam água em

suas carapaças

Coleonyx variegatus

16

15

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Elevam a parte posterior e a água escorre para a

região da cabeça

Lagartos de deserto são capazes de coletar

água de suas escamas

17

O corpo é molhado durante a chuva, e a

água se move por canais entre as escamas

das costas para a boca

Moloch horridus, Phrynocephalus

helioscopus e Phrynosoma cornutum

18

3

Phrynocephalus guttatus

Moloch horridus

19

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

12% do total da água utilizada por Dipsosaurus

dorsalis

Répteis não conseguem produzir água em

uma taxa maior que a perda evaporativa

22

21

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Produção de água metabólica é reduzida,

mas pode contribuir para a osmorregulação

de algumas espécies

Phrynosoma cornutum

20

Dipsosaurus dorsalis

23

Muito da água consumida pelos répteis vem

de sua comida

A água disponível em suas presas pode ser

a única fonte disponível por prolongados

períodos secos

24

4

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Urosaurus graciosus

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Forrageia na copa de

árvores pequenas e

arbustos durante a

manhã e no final da

tarde

Permanece inativo

durante as horas mais

quentes

Perda de água: 38,5

ml/kgdia

Urosaurus ornatus

Vive em árvores

próximas a rios

Perda de água: 27,7

ml/kgdia

25

Urosaurus graciosus

Urosaurus ornatus

Come 7,7 presas por

dia

Volume do estômago:

0,066 cm2

27

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Muitas espécies têm atividade sazonal para

minimizar a perda de água

Buscam refúgios em abrigos mais úmidos

quando estão inativos

A água é perdida durante a evaporação,

respiração e excreção

Tropidurus torquatus

28

Come 11,5 presas por

dia

Volume do estômago:

0,129 cm2

26

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

29

Nos répteis ela é perdida principalmente pelas

fezes e pela urina (apesar de concentrada)

A pele da maioria dos répteis tem baixa

permeabilidade mas, apesar disso, em

tartarugas marinhas, a maioria da água é

perdida pela pele

30

5

A água entra e sai do corpo de várias maneiras

Armazenamento de água

Crocodylus johnsoni

Passa 3 - 4 meses enterrado sem acesso a água

Com o passar do tempo, sua Tc aumenta

A perda de água é 23% menor se comparado à

perda anterior à estivação

Não desidratam e não tem mecanismo fisiológico

ligado a estivação

Refúgio deve ser local adequado para a

homeostase

Como os répteis armazenam água?

Bexiga urinária é um local comum de

armazenamento de água

Em Gopherus agassizii, elas ocupam mais da

metade da cavidade peritoneal

Meroles anchietae (estômago)

Pregas de pele ao redor da perna em Malaclemys

terrapin

Crocodylus johnsoni

32

31

33

Função dos rins

Malaclemys terrapin

Gopherus agassizii

34

Meroles anchietae

35

Produtos metabólicos e água difusa vem da

corrente sanguínea para os rins via

glomérulos

Nos tubos proximais, a glicose, aminoácidos,

Na, Cl, e a água são absorvidos

Os excretas nitrogenados são retidos

36

6

Água adicional e Na são removidos nos

tubos distais

A urina flui para os ductos urinários, para a

cloaca e então para a bexiga ou para o

intestino

Sauromalus obesus do Deserto de Mojave

mantém concentrações semelhantes de

soluto, mesmo que a disponibilidade de água

seja sazonal

37

38

Excreção do nitrogênio

40

Amônia, uréia e ácido úrico

Desidratação prolongada leva a acumulação

desses rejeitos

39

Excreção do nitrogênio

Digestão resulta na produção de rejeitos

Sauromalus obesus

Quando a vegetação (seu alimento) é abundante

eles obtém bastante água e o excesso é

eliminado

Quando não é, eles não comem e ficam inativos

onde as temperaturas são baixas

Sua perda de água é baixa nessa situação

Padrão de tipo de rejeito está mais

relacionado ao hábito que à filogenia

Animais aquáticos excretam amônia

Pode causar a morte caso não sejam eliminados

ou diluídos

41

Rapidamente sai pela pele e pelas brânquias e se

dilui na água

Muito tóxica

42

7

181

Chapter | 6 Water Balance and Gas Exchange

Excreção do nitrogênio

Problemas em ambientes marinhos

TABLE 6.2 Amphibians Known to Inhabit

or Tolerate Brackish Water

Na evolução da terrestrealidade, a evolução

favoreceu a excreção de um rejeito menos

tóxico

Uréia ou ácido úrico

Ácido úrico tem baixa solubilidade, e requer

pouca água para sua excreção

Ambystomatidae

Ambystoma subsalsum

Dicamptodon ensatus

Tartarugas marinhas, serpentes marinhas e

algumas espécies de Crocodylus vivem emPlethodontidae

Batrochoseps major

água com concentração elevada de

Plethodon dunni

salinidade

Salamandridae

Taricha granulosa

Lissotriton (¼ Triturus) vulgaris

Glândulas de sal

Sirenidae

Quase todos os lagartos e serpentes excretam

ácido úrico

Economia de água

TABLE 6.3 Occurrence of Salt Glands in Reptiles

Brachycephalidae

Eleutherodactylus martinicensis

Lineage

Leiuperidae

Pleurodema tucumanum

Chelonids, dermochelids,

and Malaclemys terrapin

Microhylidae

Gastrophyrne carolinensis

Lizards

Agamids, iguanids,

lacertids, scincids, teiids,

varanids, xantusiids

Siren lacertina

Pelodytidae

Pelodytes punctatus

Pelobatidae

Pelobates cultripes

Alytidae

Discoglossus sardus

Scaphiopodidae

Spea hammondii

Bombinatoridae

Bombina variegata

Pipidae

Xenopus laevis

Bufonidae

Anaxyrus (¼ Bufo) boreas

Pseudepidalea (¼ Bufo) viridis

Dicroglossidae

Fejervarya (¼ Rana) cancrivora

Euphlyctis (¼ Rana) cyanophlyctis

44

Hylidae

Acris gryllus

Pseudacris regilla

Ranidae

Lithobates (¼ Rana) clamitans

Homologies

Lacrymal gland

Lacrymal

salt gland

of birds

Nasal gland

None

Posterior

sublingual gland

Premaxillary

gland

None

Lingual glands

None

Snakes

Hydrophines, Acrochordus

granulatus,

Cerberus rhynchops

None

Crocodylians

Crocodylus porosus

43

Salt-secreting

gland

Turtles

Note: List includes only selected species.

Source: Adapted from Balinsky, 1981. Scientific names and families updated.

45

their eventual death. In contrast, estuarine species in the

same genus are not triggered to drink saltwater, presumably

because their skin is not permeable to saltwater and they do

not become dehydrated.

Xeric Environments

Trocas gasosas

Poucas espécies podem fazer respiração

cutânea

46

in water of varying degrees of salinity. The ionic concentration of body fluids in these species is maintained

at higher levels than in freshwater species. Much of the

increase in solutes is due to higher levels of sodium,

chloride, and urea. This response also typically occurs

when freshwater species are experimentally placed in

saltwater.

Reptiles in saline habitats tend to accumulate solutes as

the salinity level increases. Numerous species have independently evolved salt glands that aid in the removal of salt

(Table 6.3). Other species survive in saltwater because of

behavioral adjustments. The mud turtle, Kinosternon baurii,

inhabits freshwater sites that are often flooded by saltwater,

but when salinities reach 50% of saltwater, the turtle leaves

water and remains on land. One important key to the survival of reptiles in marine environments is that they do

not drink saltwater. Experiments with freshwater and estuarine species of Nerodia revealed that drinking is triggered

in freshwater species experimentally placed in saltwater,

presumably because of dehydration and sodium influx.

These snakes continue to drink saltwater,

which leads to

Some reptiles living in extreme environments can withstand

extreme fluctuations in body water and solute concentrations.

Desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) inhabit a range of environments in deserts of southwestern North America. By storing wastes in their large urinary bladder and reabsorbing

water, they minimize water loss during droughts. Nevertheless, during extended droughts, they can lose as much as

40% of their initial body mass, and the mean volume of total

body water can decrease to less than 60% of body mass.

Rather than maintaining homeostasis in the normal sense,

concentrations of solutes in the body increase with increasing

dehydration (anhomeostasis), often to the highest levels

known in vertebrates, but the most dramatic increase occurs

in plasma urea concentrations. When rainfall occurs,

increases in solute concentrations are reversed when tortoises

drink water from depressions that serve as water basins

(Fig. 6.15). Following the ingestion of water, they void the

bladder contents, and plasma levels of solutes and urea return

to levels normally seen in reptiles in general. They then store

large amounts of water in the bladder, and as conditions dry

out, the dilute urine remains hyposmotic to plasma for long

periods, during which homeostasis is maintained. When the

Buco-faringe

Baixa permeabilidade

Cloaca

Buco-faringe

Pulmões

As membranas da boca e da garganta são

permeáveis ao O2 e CO2

Espécies que ficam submersas por períodos

prolongados (e.g., hibernação)

47

Apalone, Sternotherus

48

8

Cloaca

Respiração acessória aos pulmões

Apalone

Apalone

Sternotherus

49

50

185

Chapter | 6 Water Balance and Gas Exchange

Pele

51

Chuckwalla

(Sauromalus obesus)

Boa constrictor

(Boa constrictor )

Elephant trunk snake

(Acrochordus javanicus)

Não é muito desenvolvida em répteis

Existem espécies onde as trocas de gases

pela pele podem representar de 20-30% do

total

Red-eared slider

(Trachemys scripta)

Emerald lizard

(Lacerta viridis)

Loggerhead musk turtle

(Sternotherus minor )

Tiger salamander

(Ambystoma tigrinum)

Pelagic seasnake

(Pelamis platurus)

Acrochordus, Stenotherus e Pelamis

Lacerta e Boa

Acrochordus

Bullfrog (larva)

(Lithobates catesbeianus)

Bullfrog (adult)

(Lithobates catesbeianus)

Hellbender

(Cryptobranchus alleganiensis)

Lungless salamander

(Ensatina escholtzii )

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Percent of gas exchange

52

FIGURE 6.20 Cutaneous exchange of gases in amphibians and reptiles. Open bars indicate uptake of oxygen;

shaded bars indicate excretion of carbon dioxide. Values represent the percent of total gas exchange occurring

through the skin. Adapted from Kardong, 1995.

epidermal layer of skin. This modification is carried to an

extreme in Trichobatrachus robustus, the “hairy frog,”

which has dense epidermal projections on its thighs and

flanks. These projections increase the surface area for gaseous exchange. Hellbenders, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, live in mountain streams in the eastern United States.

These large salamanders have extensive highly vascularized folds of skin on the sides of the body, through which

90% of oxygen uptake and 97% of carbon dioxide release

occurs. Lungs are used for buoyancy rather than gas

exchange. The Titicaca frog, Telmatobius culeus, which

53

54

inhabits deep waters in the high-elevation Lake Titicaca

in the southern Andes, has reduced lungs and does not surface from the depths of the lake to breathe. The highly

vascularized skin hangs in great folds from its body and

legs (Fig. 6.22). If the oxygen content is very low, the frog

ventilates its skin by bobbing. Other genera of frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (typhlonectines) have epidermal

capillaries that facilitate gas exchange.

Gas exchange in tadpoles occurs across the skin to

some degree in all species. Tadpole skin is highly permeable, similar to that of adults. Gas exchange across the

9

Stenotherus

55

Pulmões

Lacerta bilineata

56

57

59

60

Termorregulação

Principal superfície respiratória nos répteis

A troca de calor com o meio ocorre via

radiação, convecção e condução

Nenhum objeto natural absorve ou reflete

todo calor que ele recebe

Muitos répteis podem mudar o grau de

absorção mudando de cor

58

Quanto mais escuro, mais calor absorve

10

Temperatura e performance

61

A maioria dos répteis controlam suas

temperaturas corporais porque a maioria dos

processos vitais variam com a temperatura

Esses processos foram ajustados pela

seleção natural para funcionar em uma faixa

ótima dentro da atividade de cada espécie

62

Trapelus savignii

63

Altera sua tática de escape de acordo com sua

temperatura

Temperaturas mais altas ele corre (flight)

Temperaturas mais baixas ele exibe

comportamento defensivo

64

65

Tropidurus oreadicus

também é mais

“esperto” quando ele

está mais quente

Permite que o perigo

se aproxime mais

66

11

O que esperar de um lagarto noturno?

Seu ótimo deve ser em temperaturas mais

baixas?

Testes em laboratório indicam que não

Nas maiores altitudes a Tc é de 25,4°C e em

menores é de 30,2°C

68

Menor velocidade em maiores altitudes

Lagartos em maiores altitudes não estão

sobre os mesmos riscos que em menores

altitudes

70

Atividade noturna resulta em performance abaixo

do ótimo

67

Duas populações de Podarcis tiliguerta são

separadas por um gradiente vertical de 1450

m

Testes de atividade em laboratório mostram

resultados idênticos

69

As temperaturas também

podem influenciar na

performance das ninhadas

Ovos de Bassiana

duperreyi produzem

ninhadas de tamanho e

com performance diferente

dependendo do regime de

incubação

71

Ovos incubados a 20°C eclodem tardiamente

com filhotes menores que aqueles de ovos

incubados a 27°C

Ainda, os filhotes de ovos incubados a 27°C

tem melhor performance em testes de

velocidades

72

12

Controle da temperatura

Os répteis controlam sua temperatura dentro

de uma relativamente estreita faixa ótima

Muito desse controle é comportamental

Tropidurus hispidus

73

cloud interference

50

Air (sun)

Rock (shade)

Crevice (shade)

Rock (sun)

Lizard

46

42

38

34

30

26

22

0700

1100

1300

1500

1700

1900

Time of day (hr)

75

Forma do corpo

Acrochordus arafurae consegue manter sua

temperatura entre 24-35°C só escolhendo o

melhor sítio para termorregular

Muitas espécies de sangue frio se tornam

endotérmicas ou parcialmente endotérmicas

por certos períodos - homeostase parcial

As Pítons mantém uma alta temperatura

corporal quando encubam seus ovos

76

0900

FIGURE 7.11 Many lizards regulate their body temperatures within a relatively narrow range by behavioral adjustments. During morning, when rock

surfaces are relatively cool, Tropidurus hispidus basks in sun to gain heat.

As rock temperatures increase during the day, the lizards spend more time

on shaded rock surfaces or in crevices using cool portions of their habitat

as heat sinks. Late in the day, when exposed rock surfaces cool, lizards shift

most activity to open rock surfaces that remain warm and allow the lizards to

maintain high body temperatures longer. Adapted from Vitt et al., 1996.

74

Serpentes tendem a termorregular mais por

condução

Vive em afloramentos isolados na Amazônia, eles

não entram na floresta

Recebe luz por radiação

Durante o dia o substrato atinge 50°C (acima da

temperatura crítica)

De manhã, os lagartos forrageiam em rochas

mais quentes; e durante a tarde em rochas mais

frias

isolated granitic rock outcrops that receive direct sunlight.

The rain forest acts as a distribution barrier; the lizards do

not enter the shaded forest. During the day direct sunlight

causes the rock surfaces to heat up to nearly 50! C, which

is above the critical thermal maximum for most animals.

The lizards forage and interact socially on the rock surfaces, maintaining relatively constant body temperatures

throughout the day by moving between rock patches

exposed to sun and shady areas (Fig. 7.11). During morning, lizards bask on relatively cool rocks to gain heat. During afternoon, lizards use relatively cool rocks in shade as

heat sinks to maintain activity temperatures.

Even though many laboratory and field studies of

reptilian thermal ecology and physiology maintain that the

species under study thermoregulate with some degree of

accuracy, comparisons of environmental temperatures and

set temperatures are necessary to reach that conclusion.

The high-elevation Puerto Rican lizard Anolis cristatellus

lives in open habitats and basks in sun to gain heat. During

summer and winter, body temperatures of the lizards are

higher than environmental temperatures, which indicates

that they thermoregulate (Fig. 7.12). However, in summer,

environmental temperatures are higher than in winter, and

as a result, the lizards are able to achieve higher body

Temperature (!C)

Controle da temperatura

their microhabitats most of the time. Ambystomatid salamanders, for example, spend most of their lives underground. When they migrate to ponds to breed, migrations

take place during rainy nights that offer no opportunities

for behavioral thermoregulation.

Some frogs regulate body temperatures by basking in

sun (e.g., Fig. 7.2). Bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus)

vary in body temperatures from 26–33! C while active, even

though environmental temperatures vary more widely. During the day, they gain heat by basking in sun and lose heat

by a combination of postural adjustments and use of the

cold pond water as a heat sink. At night when water temperatures are low, bullfrogs move from shallow areas to

the center of the pond where water is relatively warmer.

In the morning, they return to the pond edge to bask and

gain heat. Although bullfrogs clearly cannot maintain high

body temperatures at night, they behaviorally select the

warmest patches in a relatively cool mosaic of the nighttime thermal landscape, thereby exercising some control

over their body temperatures. Similar observations have

been made on other frog species.

An alternative to moving between microsites to gain

and lose heat is to use water absorption and evaporative

water loss to moderate body temperatures. By having part

of the body against moist substrate, a frog can absorb

water to replace water lost by evaporative cooling, thereby

maintaining thermal stability even though environmental temperatures may be relatively high (see

Fig. 6.6). Likewise, by regulating evaporative water loss,

some frogs are capable of maintaining body temperatures

in cooling environments by reducing evaporative water

loss.

Control of evaporative cooling to stabilize body temperatures during periods of high ambient temperatures

occurs in other ways as well. The best-known examples

are the waterproof frogs Phyllomedusa and Chiromantis,

which allow body temperatures to track environmental

temperatures until body temperatures reach 38–40! C.

Skin glands then begin secretion and evaporative cooling

allows the frog to maintain a stable body temperature even

if environmental temperature reaches 44–45! C. Some

Australian hylid frogs in the genus Litoria are able to

abruptly decrease water loss across the skin in response

to high body temperatures and thus avoid desiccation.

Other species of Litoria with low skin resistance to water

loss are able to reduce their body temperature by evaporative water loss and thus avoid reaching potentially lethal

body temperatures. Several Litoria species have independently evolved high resistance to water loss, and it is usually associated with an increase in their critical thermal

maximum temperatures.

77

Contraindo os músculos do seu corpo

78

13

Dermochelys coriacea

Mantém sua temperatura entre 25-28°C

(ambiente: 8°C)

Metabolismo elevado

Tamanho do corpo

Eficiência na regulação térmica (fluxo sangüíneo)

Sua pele escura permite ganho de calor por

radiação

Suas taxas metabólicas são altas

Muito mais altas que outras espécies de mesmo

tamanho

O calor é mantido por uma espessa camada

de gordura na pele

79

80

81

82

83

84

14