Súmula do Processo Racional da Descoberta de

Fármacos

Eliezer J. Barreiro* 1

Professor Titular

LASSBio®, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

www.farmacia.ufrj.br/lassbio; www.farmacia.ufrj.br/im-inofar

O

processo racional de descoberta de fármacos se caracteriza pela sua

interdisciplinaridade, exigindo, portanto, competências de diversas disciplinas

que se situam entre as Ciências Biológicas e Químicas, destacando-se a Bioquímica,

Farmacologia, Química Medicinal, entre outras.

Este processo se inicia pela correta escolha do alvo-terapêutico relacionado à

patologia que se pretende tratar, passa por sua posterior validação terapêutica e pela

identificação ou descoberta de novos padrões moleculares de substâncias que representem

autênticas entidades químicas originais, i.e. novas e inovadoras, 2 capazes de serem

reconhecidas de forma eficiente - i.e. com níveis de seletividade adequados - pelos alvosterapêuticos eleitos, promovendo resposta biológica, i.e. efeito terapêutico, de preferência

por administração oral e com o menor índice de toxicidade possível.

A eleição do alvo-terapêutico é etapa crítica no sucesso desta cadeia e depende

estreitamente dos conhecimentos bioquímicos sobre a fisiopatologia da doença em estudo e

seus mecanismos farmacológicos. Desta forma, identifica-se a localização celular e

biológica do alvo-terapêutico, e.g. intra- ou extra-celular. O nível de conhecimento

estrutural que se possa ter sobre este alvo orientará, em parte, a adoção da melhor estratégia

de planejamento ou desenho estrutural dos novos padrões moleculares que serão

investigados visando-se a descoberta de novos candidatos a fármacos para o tratamento

daquela enfermidade. 3

A ABORDAGEM FISIOLÓGICA 4 E O PARADIGMA DO

COMPOSTO-PROTÓTIPO 5 NO PROCESSO RACIONAL DE

DESCOBERTA DE FÁRMACOS

Conforme antecipado, a integração do conhecimento científico próprio de diversas

disciplinas é que contribui à correta identificação do melhor alvo-terapêutico a ser eleito

para o tratamento, prevenção ou cura de uma fisiopatologia determinada o que caracteriza a

1

2

[email protected]

O. Gassmann, G. Reepmeyer, M van Zedtwitz, Leading Pharmaceutical Innovation Trends and Drivers for Growth in

the Pharmaceutical Industry, Springer, 2004.

3

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2008, 2ª edição, p. 15.

4

a) C. R. Ganellin, “General Approaches to Discovering New Drugs: An Historical Perspective” em S. M. Roberts, B. J.

Price, C. R. Ganellin, Eds., Medicinal Chemistry, Academic Press, EUA, 1992, p. 123; b) F. Chast, “A history of drug

discovery” em “The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry” 3ª edição, C-G Wermuth, Editor, Academic Press,

2008, p. 1-62

5

M. A. Lindsay, Drug Discov. Today 2005, 10, 1683.

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

2

abordagem fisiológica,25 que objetiva a identificação de novos compostos-protótipos.26 Esta

etapa da cadeia de inovação em fármacos é crítica ao sucesso neste complexo processo de

descoberta de novos fármacos 6 .

O planejamento e o desenho estrutural de novos padrões moleculares de substâncias

que possuam propriedades farmacoterapêuticas úteis, capazes de representarem novos

compostos-protótipos de fármacos, é uma tarefa complexa pela multiplicidade de fatores

que influenciam resposta terapêutica de uma substância exógena, e.g. fármaco, que precisa

apresentar elevada eficácia, reflexo das propriedades farmacodinâmicas - aquelas que

regem as interações responsáveis pelo reconhecimento molecular do fármaco pelo

biorreceptor e resultam na resposta terapêutica desejada - e farmacocinéticas - aquelas que

governam os fatores de absorção, distribuição, metabolismo e eliminação do fármaco na

biofase, resultando no perfil de biodisponibilidade.

A abordagem fisiológica, baseada no mecanismo de ação farmacológico pretendido

para o novo fármaco, se fundamenta no prévio conhecimento do processo fisiopatológico e

na conseqüente eleição do alvo-terapêutico mais adequado e busca o planejamento de

novos padrões estruturais, originais, ativos in vivo, candidatos a compostos-protótipos de

fármacos. 7

A heurística deste processo determina, portanto, que quando da eleição prévia do

alvo-terapêutico se identifique sua localização celular, e.g. membrânico, transmembrânico

ou intracelular, bem como o tipo de intervenção terapêutica que se pretenda realizar e.g.

inibição enzimática, antagonista ou agonista de biorreceptores 8 . A escolha da estratégia de

planejamento estrutural a ser adotada para o desenho molecular do novo ligante, dependerá

do nível de conhecimento da estrutura do alvo terapêutico eleito.

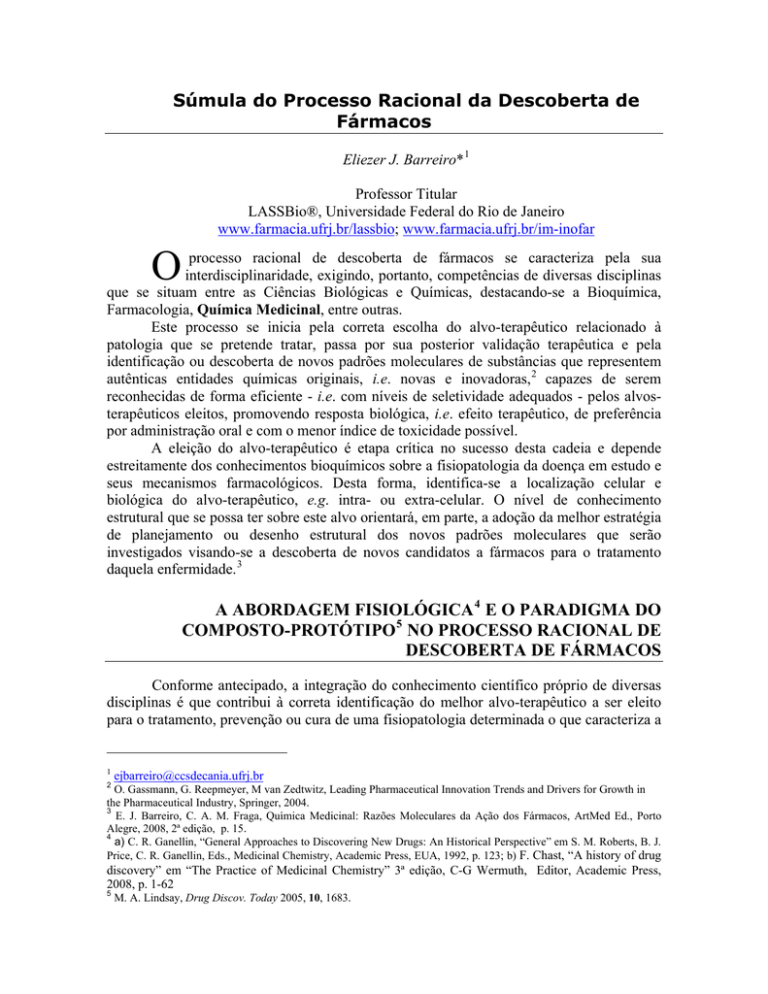

Figura 1 - A abordagem fisiológica no contexto da descoberta de fármacos segundo

a química medicinal clássica

6

R. E. Hubbard (Editor), Structure-Based Drug Discovery, RSC Publishing, Cambridge, 2006.

J. G. Lombardino, J. A. Lowe, III, Nature Rev. Drug Disc. 2004, 3, 853..

8

P. Imming, C. Sinning, A. Meyer, Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2006, 5, 821..

7

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

3

Caso seja conhecida a estrutura tridimensional (3D) do alvo-eleito e,

principalmente, aquela do sítio de reconhecimento molecular, o planejamento molecular de

ligante seletivo pode apelar para estratégias baseadas na química computacional. 9

Identificado o novo padrão estrutural este será sintetizado e avaliado através de bioensaios

in vitro que em caso de sucesso nos fornece.um novo ligante do biorreceptor eleito como

alvo-terapêutico. 10 Uma vez disponível sinteticamente em estado de pureza adequado, o

novo ligante é submetido à etapa de validação do conceito terapêutico à origem da eleição

do alvo, compreendendo o emprego de bioensaios farmacológicos, in vivo. Esta etapa é

crítica no processo pois além de validar experimentalmente o conceito terapêutico do alvo

eleito permite identificar-se as propriedades farmacocinéticas (FK) do ligante candidato a

novo composto-protótipo. Em caso de sucesso nesta etapa, temos a descoberta de novo

composto-protótipo, candidato a fármaco atuando no receptor eleito o que representa

importante resultado na cadeia de inovação em fármacos (Figura 1).

Alternativamente, quando a estrutura do alvo terapêutico não é conhecida 11 , o

desenho molecular de novos padrões estruturais do candidato a composto-protótipo

desejado, pode ser conduzido a partir do emprego de estratégias de planejamento estrutural

da Química Medicinal 12 e.g. identificação de novos análogos ativos do substrato natural do

receptor ou do agonista da enzima eventualmente eleita como alvo-terapêutico. O

planejamento molecular racional destes análogos-ativos pode se dar pelo emprego do

bioisosterismo, 13 da simplificação molecular,14 da hibridação molecular 15 , entre outras

metodologias de planejamento molecular da Química Medicinal. 16 Uma vez definidos e

sintetizados, os novos compostos são ensaiados farmacologicamente, empregando-se

protocolos in vivo, o que permite a identificação de novos compostos-protótipos de novos

fármacos.

Cabe ressaltar, que independente da estratégia adotada para o planejamento

molecular dos novos padrões estruturais dos candidatos a compostos-protótipos, deve-se,

obrigatoriamente, levar em conta todas as possíveis contribuições toxicofóricas das subunidades estruturais presentes estrutura química da série congênere de compostos

9

A pesquisa de novos candidatos a protótipos nos laboratórios de empresas farmacêuticas que descobrem fármacos ou em

spin-offs, sob contrato, pode empregar técnicas de avaliação de quimiotecas de compostos naturais ou sintéticos, obtidos

combinatoriamente, ou não, acoplados aos bioensaios robotizados que propiciam a análise de milhares de amostras de

substâncias puras ou em misturas combinatórias. A identificação de novos compostos ativos por estas técnicas, geralmente

na escala nM, representa a descoberta de um hit, que por ser um mero ligante tem que ser validado em ensaios com

animais.

10

Para um recente artigo discutindo as conceituações e distinções entre hit, ligante e composto-protótipo, veja: b) T. I.

Oprea, A. M. Davis, S. J. Teague, P. D. Leeson, J. Chem. Inf. Comp. Sci. 2001, 41, 1308.

11

C. R. Ganellin em Chronicles of Drug Discovery, D Lednicer, Ed., Wiley, 1990,

12

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2ª edição, 2008.

13

a) E.J. Barreiro Current Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 12, 23 b) G.A. Patani & E.J. LaVoie, Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 3147.

14 Para

exemplo da utilização desta estratégia no desenho de novos candidatos a protótipos de fármacos no LASSBio, veja:

E. J. Barreiro, Quim. Nova 2002, 25, 1172.

15 Para

exemplo da utilização desta estratégia no desenho de novos candidatos a protótipos de fármacos no LASSBio, veja:

A. G. M. Fraga, A. L. P. Miranda, C. A. M. Fraga, E. J. Barreiro, Eur. J. Pharm. Sc. 2000, 11, 285; Para exemplo da

utilização desta estratégia no desenho de novos candidatos a protótipos de fármacos no LASSBio-UFRJ, veja: E. J.

Barreiro,Química Nova 2002, 25, 1172.

16

D. Flower (Editor), Drug Design: Cutting Edge Approaches (Special Publication), Royal Society of Chemistry, 256 p.,

Londres, 2002; b) A. Burger, Prog. Drug Res.,1991, 36, 287; Drug Design: Cutting Edge Approaches (Special

Publication), RSC, 256 p., 2002

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

4

planejados, especialmente quanto ao potencial tóxico relacionado ao sistema microssomal

do retículo endotelial hepático, responsável por oxidações dependentes do CYP450,

essenciais à bioformação de substâncias endógenas, essenciais ao correto funcionamento de

funções fisiológicas vitais e.g. hormônios esteróidais . 17 A presença de grupos funcionais

eletrofílicos (e.g. grupos funcionais aceptores de Michael, epóxidos, i.e. intermediáriosreativos) e sub-unidades estruturais extensamente coplanares, devem ser consideradas

como atributo de potencial hepato- e citotoxicidade, respectivamente, devendo ser,

portanto, evitadas. Ademais, assim procedendo reduz-se o risco de identificarem-se,

posteriormente, propriedades tóxicas indesejáveis que condenem o composto-protótipo

descoberto.

A ETAPA DE OTIMIZAÇÃO DO COMPOSTO-PROTÓTIPO 18

Uma vez descoberto o novo composto-protótipo, a etapa seguinte na cadeia de

inovação em fármacos é sua otimização. Para tanto, nesta etapa, devem ser identificadas as

distintas contribuições farmacofóricas de todas suas sub-unidades estruturais, de maneira a

orientar as modificações moleculares a serem introduzidas na estrutura do compostoprotótipo ampliando a diversidade estrutural deste padrão molecular, o que é

significativamente relevante para a elaboração de pedidos de proteção intelectual desta

descoberta.

Na etapa de otimização do composto-protótipo, o emprego de técnicas de química

computacional aplicadas aos desenho de fármacos são particularmente úteis, e.g. QSAR,

CoMFA, CoNSIA, 19 entre outras. 20, 21 Ademais, a construção de modelos topográficos 3D

do sítio de reconhecimento molecular do biorreceptor 22 orienta, ao menos teoricamente, as

modificações moleculares necessárias à otimização das propriedades farmacodinâmias (FD)

do protótipo.

A etapa de otimização do composto-protótipo deve ser realizada simultaneamente

àquela da investigação das propriedades de biodisponibilidade do protótipo-eleito, 23 de

maneira a instruir sobre a necessidade de se introduzirem novas modificações moleculares

na sua estrutura, visando otimizar, também, suas propriedades farmacocinéticas (FK).

Ademais, este procedimento antecipa, por sua vez, preciosas informações para a futura

etapa de desenvolvimento galênico do composto-protótipo descoberto.

A realização dos ensaios de toxidez sub-aguda, compreendendo a determinação da

dose letal média e sua relação com a dose efetiva média, i.e. LD50 e ED50, respectivamente,

devem ser realizados, simultaneamente nesta etapa, de maneira a se estabelecer o provável

índice terapêutico do novo candidato a fármaco. Ensaios subseqüentes de toxidez aguda,

determinando-se histologicamente eventuais efeitos sobre a morfologia dos principais

17

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2008, 2ª edição, p 35.

18

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2008, 2ª edição, p. 108.

36

P. Gund, G. Maggiora, J. P. Snyder, “Guidebook on Molecular Modeling in Drug Design”, N. C. Cohen, Ed., Academic

Press, 1996, NY, p. 219.

37

H-D. Höltje, The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry, C-G. Wermuth, Ed., 2a edição, Academic Press, NY, 2003, p. 387.

38

A. Itai, Y. Mizutani, Y. Nishibata, N. Tomioka, Guidebook on Molecular Modeling in Drug Design, N. C. Cohen, Ed.,

Academic Press, 1996, NY, p. 93.

39

E. J. Barreiro, M. G. Albuquerque, C. M. R. Sant’Anna, R. B. Alencastro, Quim. Nova 1997, 29, 300.

23

Cf. B. M. Bolten, T. DeGregorio, Nature Rev, Drug Disc. 2002, 1, 335.

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

5

órgãos, i.e. fígado, pulmão e sistema nervoso central, além dos efeitos sobre a concentração

plasmática dos principais agentes bioquímicos, e.g. uréia, glicose, atividade transaminase,

entre outros, devem ser realizados anteriormente aos estudos pré-clínicos, em mais de uma

espécie de animais de laboratório 24 .

Neste estágio do processo, caso o composto-protótipo descoberto tenha superado

todas as etapas relatadas, consecutivamente, temos a descoberta de nova entidade molecular

(NME’s) 25 que representa, na prática, a etapa imediatamente anterior àquela dos ensaios

pré-clínicos, essenciais para que se observe o potencial de uso seguro do candidato a novo

fármaco, propriamente dito. Em caso de sucesso na descoberta de NME se deve iniciar as

negociações com os setores empresariais farmacêuticos interessados, pois representa uma

descoberta de grande valor agregado, sendo, efetivamente, um candidato a fármaco.

SÍNTESE DO COMPOSTO-PROTÓTIPO EM ESCALA

COMPATÍVEL COM O ESTADO DE DESENVOLVIMENTO NA

CADEIA DE INOVAÇÂO

A síntese multi-etapas de uma substância orgânica exige cuidadoso planejamento

preliminar, onde os diferentes estágios, envolvendo a construção de diferentes ligações CC, C-N, C-S e C-H, entre outras, traduzam uma seqüência viável, onde, por exemplo, a

compatibilidade dos diferentes grupos funcionais presentes seja previamente considerada

objetivando transformações quimiosseletivas. 26 Em sua ampla maioria os fármacos são

substâncias orgânicas de peso molecular compreendido entre 200-500 unidades de massa

atômica, contendo de cinco a sete elementos da Tabela Periódica (e.g. C, N, H. S, O, F, Cl)

e predominantemente de natureza heterocíclica e, sempre que possível, aquirais. As

distintas estratégias disponíveis na Química Orgânica Sintética se aplicam na síntese de

fármacos, em particular a retrossíntese, que permite o planejamento de maior número de

rotas sintéticas, alternativas, para um mesmo composto, identificando, inclusive,

intermediários comuns.

Os blocos estruturais a serem empregados como matéria-prima de partida definem a

facilidade e os custos da rota sintética. Há de ser salientado que a síntese de fármacos tem

características próprias, relacionadas à acessibilidade de matérias-primas, metodologias de

elevada reprodutibilidade e de bons rendimentos químicos. Nesta etapa a expertise do

químico medicinal sintético é essencial.27 Cabe menção a regra empírica definida pelo

Professor Camille Georges Wermuth (Université Louis Pasteur, Estrasburgo, Fr.), como a

Regra da Síntese Simples 28 . É necessário destacar, ainda, que não raramente a rota sintética

24

A definição do melhor momento para realizar-se a proteção intelectual desta descoberta pode ser iniciada quando o

potencial de emprego terapêutico do novo protótipo se confirme ou quando se identifique parceria no setor empresarial

farmacêutico que assegure os custos desta etapa, ou integralmente ou em parte.

25

Um excelente glossário dos principais termos de Química Medicinal, está disponível em

http://www.chem.qmw.ac.uk/iupac/medchem/ix.html

26

D. Lednicer, L. A. Mitscher, The Organic Chemistry of Drug Synthesis, Wiley, 1977, 496 pp.

27

a) W. Cabri, R. Di Fabio, From Bench to Market: The Evolution of Chemical Synthesis, Oxford University Press, 2000;

b) Fulvio Gualtieri (Editor), New Trends in Synthetic Medicinal Chemistry (Methods & Principles in Medicinal

Chemistry), Wiley-VCH, 2000, 376p.

28

C-G. Wermuth formulou sua quinta regra empírica: the easy organic synthesis (EOS) rule. O autor cita dados

estatísticos que indicam que entre os fármacos sintéticos, maioria no arsenal terapêutico contemporâneo, 62% possui um

anel heterocíclico, no mínimo, que, em geral, são de fácil acesso sintético. (The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry, C-G.

Wermuth, Ed., 3a edição, Academic Press, 2008, p. 289-300).

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

6

empregada em bancada (escala de gramas) não se presta à preparação do candidato a

fármaco em escala de quilogramas, exigindo uma interação eficaz entre o pesquisador da

síntese de bancada e este responsável pelo scale-up, preferencialmente realizado em

laboratórios localizados fora da Universidade onde se desenvolveu a etapa de bancada. 29, 30

ENGLISH VERSION

Summary of the Rational Process of Discovery of

Pharmaceuticals

Eliezer J. Barreiro* 31

Professor of Medicinal Chemistry

LASSBio®, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

www.farmacia.ufrj.br/lassbio; www.farmacia.ufrj.br/im-inofar

T

he rational process of discovery of pharmaceuticals is characterized by its

interdisplicinarity, demanding, therefore, knowledge of several subject areas

that are part of Biology and Chemistry, with an emphasis on Biochemistry, Pharmacology,

and Medicinal Chemistry, among others.

This process starts by correctly choosing the therapeutic-target related to the

pathology that one intends to treat, moves on to the later therapeutic validation and to the

identification or discovery of new molecular patterns of substances that represent authentic

original chemical entities, i.e. new and innovative, 32 capable of being recognized efficiently

- i.e. with adequate levels of selectiveness – by the therapeutic-targets chosen, promoting a

biological response, i.e. a therapeutic effect, preferably when taken orally and with the

smallest level of toxicity possible.

The choice of therapeutic-target is a critical stage in the success of this chain and

depends strictly on the biochemical knowledge of the physiopathology of the disease

studied, and its pharmacological mechanisms. As such, the cellular and biological location

of the therapeutic-target, e.g. intra- or extra-cellular, is located. The level of structural

knowledge that one can have about this target will guide, partly, the adoption of the best

29

S. Lee, G. Robinson, Process Development: Fine Chemicals from Grams to Kilograms (Oxford Chemistry Primers),

Oxford University Press, 1995, 96p

30

A. Abdel-Magid, J. A. Ragan, Chemical Process Research: The Art of Practical Organic Synthesis (ACS Symposium

S.), American Chemical Society, 2004, 323p.

31

32

[email protected]

O. Gassmann, G. Reepmeyer, M van Zedtwitz, Leading Pharmaceutical Innovation Trends and Drivers for Growth in

the Pharmaceutical Industry, Springer, 2004.

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

7

strategy for planning or structural design of the new molecular patterns that will be

investigated, aiming to discover new potential pharmaceuticals for the treatment of that

disease. 33

THE PHYSIOLOGICAL APPROACH 34 AND THE PROTOTYPECOMPOUND PARADIGM 35 IN THE RATIONAL PROCESS OF

DISCOVERY OF PHARMACEUTICALS

As anticipated, the integration of scientific knowledge specific to several subject

areas is what contributes to the correct identification of the best therapeutic-target to be

chosen for treatment, prevention, or cure of a specific physiopathology, and this is what

characterizes the physiological approach,25 which aims to identify new prototypecompounds.26 This stage of the chain of innovation in pharmaceuticals is critical to the

success of this complex process of discovery of new pharmaceuticals 36 .

The planning and structural design of new molecular patterns of substances that

have useful pharmacotherapeutic properties, capable of representing new prototypecompounds of pharmaceuticals, is a complex task due to the multiple factors that influence

therapeutic response to an exogenous substance, e.g. a pharmaceutical, which needs to have

a high efficacy, a reflex of its pharmacodynamic properties – those that react to the

interactions responsible for the molecular recognition of the pharmaceutical by the

bioreceptor and that result in the therapeutic response desired – and pharmacokinetic –

those that govern the factors of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of the

pharmaceutical in the biophase, resulting in the bioavailability profile.

The physiological approach, based on the pharmacological action mechanism

intended for the new pharmaceutical, is based on previous knowledge of the

physiopathological process and in the resulting choice of the most adequate therapeutictarget, and it aims to plan new original structural patterns, active in vivo, which are

potential prototype-compounds of pharmaceuticals. 37

The heuristics of this process determines, therefore, that at the time of the previous

choice of therapeutic-target its cellular location is identified, e.g. membranic,

transmembranic or intracellular, as well as the type of therapeutic intervention that is

intended e.g. enzymatic inhibition, bioreceptor antagonist or agonist 38 . The choice of the

structural planning strategy to be adopted for the molecular design of the new ligand will

depend on the level of knowledge of the structure of the chosen therapeutic-target.

33

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2008, 2ª edição, p. 15.

34

C. R. Ganellin, “General Approaches to Discovering New Drugs: An Historical Perspective” em S. M. Roberts, B. J.

Price, C. R. Ganellin, Eds., Medicinal Chemistry, Academic Press, EUA, 1992, p. 123

35

M. A. Lindsay, Drug Discov. Today 2005, 10, 1683.

36

R. E. Hubbard (Editor), Structure-Based Drug Discovery, RSC Publishing, Cambridge, 2006.

37

J. G. Lombardino, J. A. Lowe, III, Nature Rev. Drug Disc. 2004, 3, 853..

38

P. Imming, C. Sinning, A. Meyer, Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2006, 5, 821..

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

8

Figure 1 – The physiological approach in the context of the discovery of pharmaceuticals according

to classic medicinal chemistry

If the tridimensional (3D) structure of the chosen-target is known, and most of all,

that of the molecular recognition site, the molecular planning of the selective ligand may

appeal to strategies based on Chemoinformatics. 39 Once the new structural pattern is

identified, it will be synthesized and assessed through in vitro bioassays, which if

successful will provide us with a new ligand of the bioreceptor chosen as the therapeutictarget. 40 Once available synthetically at an adequate purity state, the new ligand is

submitted to the stage of validation of the therapeutic concept to the source of the target

choice, involving the use of in vivo pharmacological bioassays. This stage is critical to the

process because aside from experimentally validating the therapeutic concept of the chosen

target, it allows us to identify the pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of the ligand that is a

potential prototype-compound. If this stage is successful, we have discovered a new

prototype-compound, a potential pharmaceutical acting on the chosen receptor, which

represents an important result in the chain of innovation in pharmaceuticals. (Figure 1).

Alternatively, when the structure of the therapeutic-target is not known 41 , the

molecular design of new structural patterns for the desired potential prototype-compound

can be done through the use of Medicinal Chemistry structural planning strategies 42 e.g.

identification of new active analogs to the natural substract of the receptor or of the enzyme

agonist finally chosen as therapeutic-target. The rational molecular planning of these

39

The research of new potential prototypes in the laboratories of pharmaceutical industries that discover pharmaceuticals

or in spin-offs, under contract, may use evaluation techniques of chemical libraries of natural or synthetic compounds,

obtained combinatorially or not, coupled with the robotic bioassays that allow for the analysis of millions of samples of

pure substances or in combinatorial mixtures. The identification of new active compounds by these techniques, in the nM

scale, represents the discovery of a hit, which by being a mere ligand has to be validated through animal assays.

40

For a recent article discussing concepts and distinctions between hit, ligand, and prototype-compound see: b) T. I.

Oprea, A. M. Davis, S. J. Teague, P. D. Leeson, J. Chem. Inf. Comp. Sci. 2001, 41, 1308.

41

C. R. Ganellin em Chronicles of Drug Discovery, D Lednicer, Ed., Wiley, 1990,

42

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2ª edição, 2008.

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

9

active-analogs may be done through bioisosterism, 43 molecular simplification, 44 molecular

hybridization 45 , among other molecular planning methodologies used in Medicinal

Chemistry. 46 Once defined and synthesized, the new compounds are pharmacologically

essayed, using in vivo protocols, which allows for the identification of new prototypecompounds of new pharmaceuticals.

It is worth noting that regardless of the strategy adopted for the molecular planning

of the new structural standards for the potential prototype-compounds, one should

necessarily consider all the possible toxicophoric contributions of the structural subunits

present in the chemical structure of the congeneric series of planned compounds,

particularly in regard to the toxic potential of the hepatic reticulo-endothelial microsomal

system, responsible for CYP450-dependent oxidations, essential to the correct functioning

of vital physiological e.g. steroid hormones. 47 The presence of electrophilic functional

groups (e.g. Michel acceptor functional groups, epoxides, i.e. reactive-intermediates) and

extensively coplanar structural subunits, should be considered as an attribute of potential

hepatotoxicity and cytotoxicity, respectively, and should be therefore avoided.

Furthermore, with this procedure the risk to later identify undesirable toxic properties that

condemn the discovered prototype-compound is reduced.

THE STAGE OF OPTIMIZATION OF THE PROTOTYPECOMPOUND 48

Once the new prototype-compound is discovered, the next stage in the chain of

innovation in pharmaceuticals is its optimization. To do so, in this stage it is necessary to

identify the distinct pharmacophoric contributions of all of its structural sub-units, to guide

the molecular changes to be introduced in the structure of the prototype-compound,

increasing the structural diversity of this molecular standard, which is significantly relevant

for writing a petition to guarantee the intellectual property of this discovery.

During the stage of optimization of the prototype-compound, the use of

Chemoinformatics techniques applied to the design of pharmaceuticals is particularly

useful, e.g. QSAR, CoMFA, CoNSIA, among others. Furthermore, the construction of 3D

topographical models of the molecular recognition site for the bioreceptor guides, at least

theoretically, the molecular changes necessary to the optimization of the pharmacodynamic

properties (PD) of the prototype.

43

a) E.J. Barreiro Current Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 12, 23 b) G.A. Patani & E.J. LaVoie, Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 3147.

exemplo da utilização desta estratégia no desenho de novos candidatos a protótipos de fármacos no LASSBio, veja:

E. J. Barreiro, Quim. Nova 2002, 25, 1172.

45 Para

exemplo da utilização desta estratégia no desenho de novos candidatos a protótipos de fármacos no LASSBio, veja:

A. G. M. Fraga, A. L. P. Miranda, C. A. M. Fraga, E. J. Barreiro, Eur. J. Pharm. Sc. 2000, 11, 285; Para exemplo da

utilização desta estratégia no desenho de novos candidatos a protótipos de fármacos no LASSBio-UFRJ, veja: E. J.

Barreiro,Química Nova 2002, 25, 1172.

46

D. Flower (Editor), Drug Design: Cutting Edge Approaches (Special Publication), Royal Society of Chemistry, 256 p.,

Londres, 2002; b) A. Burger, Prog. Drug Res.,1991, 36, 287; Drug Design: Cutting Edge Approaches (Special

Publication), RSC, 256 p., 2002

47

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2008, 2ª edição, p 35.

48

E. J. Barreiro, C. A. M. Fraga, Química Medicinal: Razões Moleculares da Ação dos Fármacos, ArtMed Ed., Porto

Alegre, 2008, 2ª edição, 108.

44 Para

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

10

The optimization stage of the prototype-compound should be carried out

simultaneously to that of the investigation of the bioavailability properties of the chosenprototype, so as to inform the need to introduce new molecular changes to its structure, to

optimize, also, its pharmacokinetic (PK). Furthermore, this procedure anticipates, as it is,

precious information for the future stage of galenic development of the prototypecompound discovered.

Conducting the sub acute toxicity assays, to establish the average lethal dosage and

its relation to average effective dosage, i.e. LD50 and ED50, respectively, should be done

simultaneously at this stage, so as to establish the probable therapeutic index of the new

prospective pharmaceutical. Further acute toxicity assays, to establish histologically any

possible effects on the morphology of the main, i.e. liver, lungs, and central nervous

system, as well as the effects on the plasmatic concentration of the main biochemical

agents, e.g. urea, glucose, aminotransferase activity, among others, should be carried out

prior to the pre-clinical trials, on more than one species of laboratory animals.

At this stage of the process, if the prototype-compound discovered has overcome all

the described stages, consecutively, we will have the discovery a new molecular (NMEs)

which represents in actuality the stage immediately before that of pre-clinical trials,

essential for the observation of the safe use of the new potential pharmaceutical itself. If

the discovery of the NME is successful, negotiation with interested parties from

pharmaceutical industries should begin, because it is a discovery that has great earned

value, as it is effectively a potential pharmaceutical.

SYNTHESIS OF THE PROTOTYPE-COMPOUND IN A SCALE

COMPATIBLE WITH THE STATE OF DEVELOPMENT IN THE

CHAIN OF INNOVATION

The multi-stage synthesis of an organic substance requires careful preliminary

planning, where the different stages involving the construction of different C-C, C-N, C-S,

and C-H links, among others, translate a viable sequence, where, for example, the

compatibility of different functional groups is previously considered with the goal of

chemoselective changes. 49 The vast majority of pharmaceuticals are organic substances of a

molecular weight between 200 and 500 units of atomic mass, containing between five and

seven elements of the Periodic Table (e.g. C, N, H. S, O, F, Cl), and predominantly of a

heterocyclic nature, and whenever possible, achiral. The distinct strategies available in

Synthetic Organic Chemistry apply to the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, particularly

retrosynthesis, which allows the planning of the largest number of alternative, synthetic

routes for the same compound, also identifying common intermediaries.

The structural blocks that will be used as raw materials to start with define the ease

and the costs of the synthetic route. It should be highlighted that the synthesis of

pharmaceuticals has its own characteristics, related to the accessibility of raw materials,

methodologies that have high reproducibility, and good chemical yield. At this stage, the

49

D. Lednicer, L. A. Mitscher, The Organic Chemistry of Drug Synthesis, Wiley, 1977, 496 pp.

Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia Inovação e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos e Medicamentos – INCT-INOFAR

11

expertise of the synthetic medicinal chemist is essential.50 It is worth noting the empirical

rule established by Professor Camille Georges Wermuth (Université Louis Pasteur,

Strasbourg, Fr.), as the Rule of Simple Synthesis 51 . It is necessary to highlight, also, that

often the synthetic route used on bench-scale (gram scale) is not useful for the preparation

of the potential pharmaceutical at a scale of kilograms, and this demands an efficient

interaction between the research of the synthesis in the laboratory and the person

responsible for the scale-up, which should ideally take place in laboratories outside of the

University where the bench-scale was developed. 52, 53

50

a) W. Cabri, R. Di Fabio, From Bench to Market: The Evolution of Chemical Synthesis, Oxford University Press, 2000;

b) Fulvio Gualtieri (Editor), New Trends in Synthetic Medicinal Chemistry (Methods & Principles in Medicinal

Chemistry), Wiley-VCH, 2000, 376p.

51

C-G. Wermuth formulated his fifth empirical rule: the easy organic synthesis (EOS) rule. The author quotes statistical

data that indicate that among synthetic pharmaceuticals, which are the majority in our current therapeutic choices, 62%

have a heterocyclic ring, at least that, in general, are of easy synthetic access. (The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry, C-G.

Wermuth, Ed., 3rd edition, Academic Press, 2008, p. 289-300).

52

S. Lee, G. Robinson, Process Development: Fine Chemicals from Grams to Kilograms (Oxford Chemistry Primers),

Oxford University Press, 1995, 96p

53

A. Abdel-Magid, J. A. Ragan, Chemical Process Research: The Art of Practical Organic Synthesis (ACS Symposium

S.), American Chemical Society, 2004, 323p.