CENTRO UNIVERSITÁRIO DO MARANHÃO

PRÓ-REITORIA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO, PESQUISA E EXTENSÃO

PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA PARASITÁRIA

Padrão de Virulência da Escherichia coli

enteroagregativa e enteropatogênica atípica

SÃO LUÍS

2010

THIAGO AZEVEDO FEITOSA FERRO

PADRÃO DE VIRULÊNCIA DA ESCHERICHIA COLI ENTEROAGREGATIVA E

ENTEROPATOGÊNICA

Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de PósGraduação em Biologia Parasitária como parte

dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de

Mestre em Biologia Parasitária.

Orientador: Profa. Dra. – Patrícia Figueiredo

Co-orientador: Prof. Dr – Valério Monteiro Neto

SÃO LUÍS

2010

Ficha Catalográfica

Ferro, Thiago Azevedo Feitosa

Padrão

de

Virulência

da

Escherichia

coli

enteroagregativa

e

enteropatogênica atípica: / Thiago Azevedo Feitosa Ferro. São Luís:

UNICEUMA, 2010.

94p.:il.

Dissertação (Mestrado) - Mestrado em Biologia Parasitária. Centro

Universitário do Maranhão, 2010.

1. Escherichia coli. 2. Biologia Parasitária I. Figueredo, Patrícia Maria

S. (Orientador) II. Título.

CDU:573:576.8

AGRADECIMENTOS

À Deus, que me protegeu durante a realização deste trabalho.

À minha esposa Carla Danielle e ao meu filho Iago, pelo carinho,

compreensão e constante incentivo.

À Profa. Dra Patrícia Figueredo, que conduziu esse projeto com muito

interesse e competência.

Aos Profs Dr Valério Monteiro e Dra Cristina Monteiro, pelo auxílio e

prontidão.

Aos colegas de laboratório pela colaboração direta ou indireta para com este

trabalho.

Ao meu pai Aderson e minha mãe Solange, pelo sempre e incondicional

carinho e estímulo.

Ao Centro Universitário do Maranhão, em especial ao departamento de

Pesquisa de Biologia Parasitária, e ao Fundo de Apoio a Pesquisa do Estado do

Maranhão.

SUMÁRIO

LISTA DE FIGURAS ................................................................................................... i

LISTA DE TABELAS .................................................................................................. ii

LISTA DE ABREVIATURAS ..................................................................................... iii

RESUMO ................................................................................................................... v

ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................... vi

1.

INTRODUÇÃO .................................................................................................. 14

2. REVISÃO BIBLIOGRÁFICA ................................................................................. 16

2.1.Hemolisinas ................................................................................................. 18

2.2.Adesão ........................................................................................................ 19

2.3 Resistência à antibióticos ............................................................................ 20

3. OBJETIVOS ......................................................................................................... 22

3.1. Objetivo Geral ............................................................................................. 22

3.2. Objetivos Específicos ................................................................................. 22

4. METODOLOGIA .................................................................................................. 23

4.1. Identificação do patógeno ........................................................................... 23

4.2. Identificação molecular das categorias patogênicas de Escherichia coli e

seus marcadores de virulência ................................................................................. 23

4.2.1. Eletroforese de DNA em gel de agarose .................................................. 24

4.3. Detecção da atividade hemolítica .............................................................. 28

4.3.1. Pesquisa da atividade hemolítica em meio sólido .................................... 28

4.3.2 Pesquisa da atividade hemolítica no sobrenadante da cultura .................. 28

4.3.3. Pesquisa de hemólise de contato ............................................................ 29

4.4. Infulência da presença de íons, quelantes, protetores osmóticos e soro na

atividade da hemolisina ........................................................................................... 29

4.4.1 Cultivo na presença de agentes quelantes e íons ..................................... 29

4.4.2. Teste de hemólise com protetores osmóticos .......................................... 30

4.4.2. Inibição da atividade hemolítica por soro ................................................. 30

4.5.Produção de biofilme ................................................................................... 30

4.5.1. Produção de biofilme em Ágar Vermelho Congo ..................................... 30

4.5.2. Produção de biofilme em microplaca ....................................................... 31

4.6. Identificação de fímbrias ............................................................................. 32

4.6.1. Identificação de fímbria curli .................................................................... 32

4.6.2. Identificação de fímbria tipo I ................................................................... 32

4.7. Resistência ao soro .................................................................................... 32

4.8. Teste de resistência aos antimicrobianos ................................................... 34

4.9. Análise estatística ....................................................................................... 34

5. RESULTADOS ..................................................................................................... 36

5.1.1.Pesquisa de hemolisina ............................................................................ 36

5.1.2.Influência de diferentes condições de cultivo na atividade hemolítica ....... 37

5.2.Produção de biofilme ................................................................................... 40

5.3. Identificação de isolados produtores de fímbrias: curli e fímbria tipo I ........ 41

5.4. Categorizçaão dos marcadores de virulência entre os isolados .................. 42

5.5. Resistência aos antimicrobianos................................................................. 44

5.6. Resistência aos ao soro ............................................................................. 47

5.7. Prevalência entre marcadores e fatores de virulência dos isolados de EAEC

e EPEC .................................................................................................................... 48

6. DISCUSSÃO ........................................................................................................ 51

7.CONCLUSÃO ....................................................................................................... 57

8.REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ...................................................................... 58

APÊNDICE A – American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Instructions for

Authors .................................................................................................................... 64

8.APÊNDICE B - SUBMISSÃO ................................................................................ 75

8.APÊNDICE C - ARTIGO ....................................................................................... 76

i

LISTA DE FIGURAS

Fig 1. Hemólise de eritrócito de carneiro, dos quatro isolados com atividade

hemolítica, na presença de íons de cálcio, férrico, níquel e magnésio; dos quelantes

EDDA e EDTA; meio puro; e Soro normal humano. Está descrito a média, as suiças

representamo desvio padrão. ● representa o valor máximo ou mínimo da atividade

hemolítica ................................................................................................................ 40

Fig 2. Categorização da produção de biofilme entre isolados de EAEC e EPEC

atípica por análise realizado por espectrofotometria. D.O.i/D.O.c - razão entre a

absorbância do isolado e do controle negativo.

X

- valor da razão da absorbância

igual a 2. .................................................................................................................. 41

Fig. 3. Sobrevivência de isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica, por tempo de

incubação, em soro humano normal (A), soro tratado com EDTA (B) e soro inativado

por aquecimento a 56ºC por 30 minutos. Os resultados estão representados como a

média dos isolados distribuídos nas três categorias (sensível, resistência

intermediária e resistente) realizados em experimentos individuais. A sobrevivência

relativa, no tempo inicial foi considerada como 100%. * - apenas um isolado foi

categorizado para cada uma das linhas assinaladas ............................................... 48

ii

LISTA DE TABELAS

Tabela 1. Linhagens bacterianas estudadas neste trabalho ..................................... 24

Tabela 2. Relação de marcadores de virulência utilizados neste estudo .................. 26

Tabela 3 . Expressão de hemolisina de Escherichia coli em placas de Muller-Hintonsangue, com diferentes hemácias, observada em diferentes tempos (horas) de

cultivo....................................................................................................................... 37

Tabela 4. Atividade hemolítica de isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica em sangue de

carneiro com diferentes constituintes de cultivo EAEC e EPEC atípica em sangue de

carneiro com diferentes constituintes de cultivo. ...................................................... 39

Tabela 5. Presença de curli, Fímbria tipo I e Produção de Biofilme entre os isolados

de EAEC e EPEC atípica. ........................................................................................ 42

Tabela 6.Distribuição de beta-lactamases de espectro estendido (ESBL) entre os

isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica. .......................................................................... 43

Tabela 7. Distribuição de marcadores de virulência entre Escherichia coli

enteroagregativa e enteropatogênica atípica............................................................ 44

Tabela 8. Perfil de sensibilidade a antimicrobianos dos isolados de EAEC e EPEC

atípica.,. ................................................................................................................... 46

Tabela 9. Frequência relativa e absoluta dos fatores de virulência, marcadores e

genes responsáveis pela produção de beta-lactamases de espectro estendido

(ESBL).,. .................................................................................................................. 50

iii

LISTA DE ABREIATURAS

AVC – Ágar Vermelho Congo

bfp – pilus em forma de cacho

BHI – Infusão de cérebro e coração

cdt – Toxina citoletal distensora

DAEC – Escherichia coli difusamente aderente

D.O.c. – Densidade óptica do controle

D.O.i. – Densidade óptica do isolado

EAF – plasmídio de fator de aderência da Escherichia coli enteropatogênica

EAEC – Escherichia coli enteroagregativa

EAST - Enterotoxina termoestável de E. coli enteroagregativa

EDDA - Etileno-di (o-hidroxifenol) ácido acético

EDTA - Etilenodiamina-tetra ácido acético

efa1 – EHEC fator de aderência

EHEC – Escherichia coli enterohemorrágica

ehx - enterohemolisina

EIEC – Escherichia coli enteroinvasora

EPEC – Escherichia coli enteropatogênica

ESP – Espectofotometria

iv

ESBL – beta-lactamase de espectro estendido

ETEC - Escherichia coli enterotoxigênica

HEp-2 - Células de carcinoma de laringe humana

HMR – Hemaglutinação Manose Resistente

HMS – Hemglutinação Manose Sensível

iha – adesina homóloga a irgA

irp – Sideróforo yersiniabactina

LEE – locus de apagamento do enterócito

LB – meio Luria Bertani

LT – toxina termolábil

pAA – plasmídio de aderência agregativa

PBS - Tampão fosfato salina

PCR – Reação em cadeia da Polimerase

RTX – Toxina de estrutura repetida

ST – toxina termoestável

TBE – Tris borato Etilenodiamina-tetra ácido acético

UNICEUMA – Centro Universitário do Maranhão

v

RESUMO

Escherichia coli é um microorganismo Gram-negativo pertencente ao grupo dos

coliformes, e um importante agente de diarreia infantil. Ela pode possuir diferentes

fatores de virulência e esses são definidos como estruturas, produtos ou estratégias

que contribuem para o microorganismo aumentar sua capacidade em causar a

infecção. O presente estudo tem como objetivo investigar presença destes fatores

em isolados obtidos de casos clínicos de diarreia infantil e interrelacioná-los.

Dezenove isolados de Escherichia coli, entre linhagens de enteropatogênico e

enteroagregativo, foram caracterizados quanto aos diferentes fatores de virulência

por análises fenotípicas e genotípicas. Cerca de 94% dos isolados apresentaram

resistência ao soro, 78% fímbria curli, 73% produção de biofilme em diferentes

níveis, 68% algum gene para produção de beta-lactamases, 21% produção de

hemolisina, 15% fímbria tipo I e 10% o sideróforo yersiniabactina. Os isolados com

atividade hemolítica apresentaram maior número de fatores de virulência. Em

relação hemólise, foi visto que e que esta atividade foi mais forte nos meio que

continham EDDA; diminuída nos que continham ferro e EDTA; e similares nos que

continham cálcio e soro humano. Esses resultados sugerem que os isolados de

Escherichia coli enteropatogênico atípico e enteroagregativo, caracterizados neste

estudo, são heterogêneos quanto à presença dos fatores de virulência,não sendo

possível associar quaisquer destas propriedades ou combinação.

vi

ABSTRACT

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative microorganism belong to the coliforms group,

and a important diarrheal childhood agent. Its can presents different virulence factors

and theses is defined like structures, products or strategies which to contribute the

microorganism increase your capacity in cause infection. The present study aims at

investigating the presence theses factors in isolates of Escherichia coli from clinical

diarrheal cases and interrelating them. Twenty nine isolates of Escherichia coli,

between enteropathogenic and enteroaggregative strains, were characterized due to

the different virulence factors for phenotypic and genotypic analysis. About 94% the

isolates presented resistance to the serum, 78% curli fimbriae, 73% biofilms

production in different levels, 68% some gene to the beta-lactamases production,

21% hemolysin production, 15% fimbriae type I and 10% yersiniabactin siderophore.

The isolates with hemolytic activities presented more virulence factors. About

hemolysis; this activity was stronger at medium with EDDA; decreased at medium

with iron and EDTA; and similar in medium with calcium and human serum. Theses

results suggest that the isolates of atypical enteropathogenic and anteroaggregative

Escherichia coli, characterized in this study, are heterogeneous as to the presence

his virulence factors, without correlation among these proprieties or combination

them.

14

1. INTRODUÇÃO

Um levantamento realizado pela Organização Mundial de Saúde, de 2000 a

2003, constatou que 73% dos 10,6 milhões de mortes anuais de crianças menores

de cinco anos estavam relacionados a cinco causas, sendo a doença diarréica a

segunda mais comum com 18%, depois da pneumonia com 19%, o que demonstra a

importância da enfermidade para a saúde pública, uma vez que causa profundos

impactos sobre as taxas de morbidade e mortalidade infantil, principalmente nas

regiões menos desenvolvidas do mundo (BRYCE et al., 2005).

Apesar dos estudos mais recentes demonstrarem que houve uma redução

significativa nos índices de mortalidade infantil por diarréia de 4,6 milhões por ano

para aproximadamente 2,5 milhões por ano em todo o mundo, tais valores ainda são

considerados altos e os índices de morbidade permanecem tão elevados quanto os

observados há 30 anos (KOSEK, BERN, GUERRANT, 2003). Altas taxas de

morbidade por doença diarréica são preocupantes porque a diarréia infantil pode

deixar seqüelas que se manifestarão em longo prazo sobre o desenvolvimento físico

e cognitivo da criança (BLACK, BROWN, BECKER, 1984).

Vários patógenos estão relacionados com a diarreia no ser humano. Entre

os agentes que são classicamente reconhecidos, destacam-se alguns vírus

(Adenovírus, Astrovírus, Rotavírus), parasitos intestinais (Entamoeba hystolitica,

Giardia lamblia, Strongyloides stercoralis) e bactérias (Aeromonas, Campylobacter,

Clostridium dificille, Plesiomonas shigelloides, Salmonella enterica, Shigella, Vibrio

Escherichia coli enteropatogênica, E. coli enterotoxigênica, E. coli enteroinvasora,

E. coli enterohemorrágica, E. coli enteroagregativa). Apesar dessa ampla variedade

de agentes etiológicos, linhagens de Escherichia coli são os mais prevalentes na

15

infância e representam o maior problema de saúde pública em países em

desenvolvimento (DENNEHY, 2005; MOYO et al., 2007).

Deste modo, as cepas diarreiogênicas da E. coli são categorizadas segundo

suas propriedades de virulência. Estas características são definidas como

estruturas, produtos ou estratégias que contribuem para a bactéria aumentar sua

capacidade em causar infecção (BUERIS et al., 2007).

Entre estas propriedades, destacam-se aquelas que permitam à bactéria

reconhecer e colonizar a superfície das células do hospedeiro (adesinas fimbriais e

não-fimbriais); a produção de toxinas e hemolisinas; expressão de sistemas de

captação de ferro (sideróforos); e resistência a antibióticos e ao sistema

imunológico.

Contudo, apesar da sua elevada prevalência, a enteropatogenicidade de

algumas

dessas

linhagens

ainda

não

está

completamente

estabelecida,

principalmente para E. coli enteropatogênica (EPEC) e E. coli enteroagregativa

(EAEC) (NATARO, KAPER, 1998; TRABULSI, KELLER, TARDELLI GOMES, 2002;

BOISEN et al., 2008). Isto se deve há poucos estudos sistemáticos sobre suas

propriedades de virulência e a heterogeneidade destas características (MULLER et

al., 2006; FLORES, OKHUYSEN, 2009; REGUA-MANGIA et al., 2009; TENNANT et

al., 2009).

Desta forma, a presente proposta visa abordar algumas das lacunas de

conhecimentos existentes com relação aos aspectos de virulência da EAEC e EPEC

em casos de diarreia infantil presentes na cidade de São Luís e em áreas de

“ressaca”, na cidade de Macapá. Isto se torna relevante devido à falta de estudos

que abordem esta temática nas regiões mencionadas.

16

2. REVISÃO BIBLIOGRÁFICA

E. coli

apresenta-se como um bacilo Gram-negativo,

não esporulado,

usualmente móvel, devido a presença de flagelos peritríquios, que frequentemente

apresenta fímbrias e cápsula. É um anaeróbio facultativo, capaz de se desenvolver

por metabolismo fermentativo (KAPER, NATARO, MOBELY, 2004).

Algumas

linhagens

podem

proporcionar

benefícios

ao

organismo

hospedeiro. Estas linhagens fazem parte da microbiota normal do trato intestinal e

ajudam a prevenir possíveis infecções por bactérias patogênicas, além de

sintetizarem vitaminas úteis ao bom funcionamento do organismo. Entretanto

algumas cepas patogênicas podem provocar diversos cenários clínicos, como:

meningites, infecção do trato urinário, diarreia e sepse (FERRIERES, HANCOCK,

KLEMM, 2007b; SHARMA, YADAV, CHAUDHARY, 2009).

Escherichia coli patogênica é agrupada em categorias baseadas pela

produção de fatores de virulência. Virulência é definido como a habilidade de um

organismo provocar doença em um hospedeiro particular, devido ao impacto

cumulativo de um ou vários fatores de virulência (NAVEEN, MATHAI, 2005).

Dentre as E. coli diarreiogênicas duas linhagens se destacam na prevalência

da diarreia infantil, a enteropatogênica (EPEC) e a enteroagregativa (EAEC). A

EPEC é o principal agente em crianças menores de seis meses de idade. Este

patógeno causa lesão histopatológica conhecida como “adesão e apagamento”

(attaching and effacement). Todas as linhagens apresentam uma ilha de

patogenicidade cromossomial denominada locus de apagamento do enterócito

(LEE) (BUERIS et al., 2007)

Contudo, devido ao seu perfil genético, esta linhagem pode ser subdividida

em típica e atípica. A ausência do plasmídio denominado fator de aderência da

17

EPEC (EAF), responsável pela produção do pilus em forma de cachos (bfp), é o que

caracteriza a linhagem de EPEC atípica. De forma geral, EPEC atípica é mais

heterogênea nas suas características de virulência do que a EPEC típica, pois

apresenta outros marcadores de virulência dispersos em ilhas de patogenicidade

além das regiões LEE e EAF. Por outro lado, atualmente, apresenta uma maior

prevalência quando comparado com a EPEC típica (TRABULSI et al., 2002; BUERIS

et al., 2007).

Já a EAEC tem emergido como um importante patógeno em vários cenários

clínicos, incluindo diarreia do viajante e diarreia persistente entre pacientes

pediátricos e HIV positivos. É definido como a linhagem que não secreta as toxinas

termoestável (ST) e termolábel (LT) da E. coli

enterotoxigênica (ETEC) e

caracterizada pelo padrão de aderência agregativa a culturas de células HEp-2. Os

genes específicos da EAEC são controlados pelo regulador global denominado

AggR. Este é codificado pelo plasmídio de aderência agregativa (pAA) (BOISEN et

al., 2008).

Devido ao seu padrão de virulência heterogêneo, a EAEC pode causar uma

ampla variedade de danos ao hospedeiro: encurtamento das vilosidades; necrose

hemorrágica das pontas das vilosidades; resposta inflamatória média com edema e

infiltração mononuclear da submucosa (NATARO, STEINER, GUERRANT, 1998).

Estas características de patogenicidade habilitam as amostras portadoras a

realizarem uma gama variada de funções, como: processos de adesão; invasão e/ou

destruição de tecidos; produção de toxinas; ou captação de produtos essenciais ao

hospedeiro. A combinação destes fatores é determinante para a instalação da

doença e sua severidade.

18

2.1 Adesão

O primeiro estágio para que as linhagens de E. coli iniciem um processo

infeccioso é a adesão. Isto invoca uma estratégia das bactérias fixarem nas células

do hospedeiro e expressarem outras propriedades da sua patogenicidade. A

capacidade de aderir de maneira firme é mediada por organelas de superfície

bacteriana denominada adesinas ou fatores de colonização, que podem ser

classificadas, de maneira geral, em estruturas protéicas ou exopolissacarídeos, nas

quais permitem a liberação de toxinas para o interior da célula do hospedeiro e/ou a

invasão desta, sendo o passo inicial na patogenicidade de E. coli diarreiogênica

(SHERLOCK et al., 2004; SHERLOCK, VEJBORG, KLEMM, 2005).

As

adesinas

de

natureza

polissacarídica

compreendem

cápsulas

bacterianas, capazes de promover adesão inespecífica as células e outras

superfícies. Há também estruturas fimbriais, que são estruturas protéicas

filamentosas que podem apresentar ligação específica e inespecífica. Deste modo a

E. coli diarreiogênica pode apresentar dois tipos principais de fímbrias: fímbria tipo 1

e a curli. A fímbria tipo 1 tem a capacidade de aglutinar eritrócitos e aderir a uma

grande variedade de células (OTTO et al., 2001).

Curli é uma adesina produzida por algumas linhagens do gênero da

Escherichia e Salmonella, que se liga a proteínas do hospedeiro e ativa mediadores

inflamatórios. Ela tem o papel na autoagregação bacteriana e na formação de

biofilme. Estudos argumentam que as linhagens portadoras desta estrutura são,

geralmente, mais invasoras, o que contribuiria para sepse bacteriana (UHLICH,

KEEN, ELDER, 2002; UHLICH, COOKE, SOLOMON, 2006; DYER et al., 2007)

19

2.2 Hemolisinas

Após a colonização dos tecidos do hospedeiro a E. coli pode apresentar a

capacidade de expressar toxinas com distintas finalidades. Dentre estas a

hemolisina demonstra um importante papel na virulência pois promove atividade

citolítica, preferencialmente, de eritrócitos. Esta proteína é importante para obtenção

de ferro e assim favorecer o crescimento bacteriano. Alguns isolados de E. coli são

capazes de produzir simultaneamente vários tipos de hemolisinas (FIGUEIREDO,

CATANI, YANO, 2003; HUNT et al., 2008).

O isolamento de cepas hemolíticas de E. coli estimulou o interesse na

importância da hemolisina na doença diarréica. Há três tipos principais desta

proteína: α-hemolisina, β-hemolisina e enterohemolisina (WYBORN et al., 2004;

HUNT et al., 2008; ALDICK et al., 2009).

Dentre estas toxinas mencionadas anteriormente, a α-hemolisina é a mais

prevalentes nas cepas diarreiogências e pertence a um grupo de toxinas formadoras

de poros, liberada no meio extracelular, agrupada na família das toxinas de estrutura

repetida (RTX). RTX são toxinas que foram primeiramente caracterizadas como

hemolisinas e leucotoxinas, mas também afetam células endoteliais e renais Esta

hemolisina pode ser sintetizada, também, por Proteus e Morganella spp., Pasteurella

hemolytica, e Actinobacillus spp. (VALEVA et al., 2005; SKALS et al., 2009).

Como a α-hemolisina, a enterohemolisina é uma RTX, contudo ela não é

liberado no meio extracelular. Os primeiros relatos de linhagens de E. coli produtoras

de enterohemolisina se deu em casos de epidemia de diarreia infantil na Alemanha e

Estados Unidos (ALDICK et al., 2009; SASAKI et al., 2009)

Ainda não se sabe ao certo o papel destas toxinas no processo diarréico,

mas se tem estabelecido que alguns isolados produtores de hemolisinas tendem a

20

aumentar os níveis de citocinas proinflamatórias, e que isto contribui para o quadro

clínico do hospedeiro (COOKSON et al., 2007).

. 2.3 Resistência à antibióticos

Além dos fatores supracitados, outra importante estratégia para a

sobrevivência encontrada entre Enterobacteriaceae

e que vem aumentando no

mundo, é denominada fator de resistência à antimicrobianos (fator R). O principal

mecanismo de resistência é a produção de β-lactamases de espectro estendido

(ESBL). O tratamento de

infecções

causadas por

cepas produtoras de ESBL

oferece um substancial desafio à terapia antimicrobiana, pois as ESBLs são

capazes

de hidrolisar

monobactâmicos,

penicilinas,

minimizando

cefalosporinas

as

opções

de

todas as

terapêuticas

gerações

e

(CHAUDHARY,

AGGARWAL, 2004).

As ESBLs são um grupo heterogêneo de enzimas que são codificadas por

genes plasmidiais. Estas enzimas atualmente são compostas por cerca de 890

enzimas distintas, cujo o grau de resistência varia para cefalosporinas, penicilinas e

inibidores de β-lactâmicos (SLAMA, 2008; HAWSER et al., 2009; BUSH, JACOBY,

2010).

A primeira enzima bacteriana responsável pela destruição da penicilina foi a

β-lactamase Amp-C produzida pela E.coli em 1940 (JACOBY, 2009). Pacientes com

infecções devido a enterobactérias produtoras de β-lactamases de espectro

estendido (ESBL) apresentam um resultado menos satisfatório, pois está associado

com alta taxa de falha no tratamento (>80%) e mortalidade (>35%) (PEREZ et al.,

2008).

21

Uma recente mudança da distribuição de ESBLs têm ocorrido em várias

partes do mundo, com aumento das enzimas CTX-M em relação as variantes TEM e

SHV. Embora ESBLs continuam sendo a primeira causa constitutiva de betalactâmicos entre Enterobacteriacea, outros tipos recentes destas enzimas estão

conferindo resistência a carbapenens, como as metalo-beta-lactamases ou

cefamicinas, como a enzima CMY (COQUE, BAQUERO, CANTON, 2008)

22

3 OBJETIVOS

3.1 OBJETIVO GERAL

Detectar a presença de fatores de virulência em amostras de

Escherichia coli enteropatogênica atípica e Escherichia coli enteroagregativa

isoladas de fezes de crianças entre 0-5 anos das cidades de São Luís e Macapá.

3.2. OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS

Identificar os possíveis marcadores de virulência nos isolados;

Caracterizar a atividade hemolítica;

Avaliar o tipo de fímbrias e a produção de biofilme;

Determinar o perfil de resistência antimicrobianos;

Detectar a presença de ESBL

23

4. METODOLOGIA

4.1. População estudada

De abril de 2009 a março de 2010 amostras de fezes de 204 crianças (até

cinco anos de idade) foram coletadas como parte de um estudo de caso e controle

realizado nas cidades de São Luís e Macapá, Brasil. Casos foram caracterizados

como crianças que apresentaram 3 ou mais evacuações em período de 24 horas de

fezes pastosas ou líquidas. O grupo controle foi caracterizado como crianças que

não apresentavam qualquer sintoma gastrointestinal de pelo menos 30 dias anterior

a inclusão nesta pesquisa. O estudo global de caso-controle consistia de 102 casos

e 102 controles.

4.2. Identificação do patógeno

Amostras de fezes coletadas em meio transporte Cary-Blair foram cultivadas

em meio agar MacConkey para selecionar isolados de E. coli. Colônias com

morfologia presumidamente de E. coli foram selecionadas e submetidas a testes

bioquímicos. Isolados de E. coli foram estocados a -80ºC em infusão de cérebro e

coração (BHI) com 20% de glycerol para posterior procedimentos.

Os isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica são apresentados, segundo sua região

de origem (São Luís ou Macapá), na tabela abaixo.

24

Tabela 1. Linhagens bacterianas estudadas neste trabalho

Linhagem

Identificação Laboratorial

Origem

A2

Macapá

A 17

São Luís

A3

Macapá

A 16

São Luís

A7

São Luís

EAEC

A 10

São Luís

A5

São Luís

A 19

São Luís

A 15

Macapá

A 14

São Luís

A9

Macapá

EPEC Atípica

A 12

A1

A4

A6

A 18

A 11

A8

A 13

Macapá

Macapá

Macapá

São Luís

São Luís

Macapá

Macapá

Macapá

4.3. Identificação molecular das categorias patogênicas de Escherichia

coli e seus marcadores de virulência

Foram analisadas,

em média,

4 isolados bacterianos identificados

bioquimicamente como E. coli em cada amostra de fezes. As bactérias foram

submetidas, inicialmente, à técnica de reação em cadeia da polimerase (PCR). A

pesquisa incluiu a detecção dos seguintes genes ou regiões conservadas de DNA,

para análise do tipo de linhagem de E. coli diarreiogênica: eae (para EPEC e EHEC),

stx1 e stx2 (para EHEC), elt e est (para ETEC), ipaH (para EIEC) e aggR (para

EAEC) (TOMA et al., 2003). Para tanto utilizou-se como cepas diarreiogênicas

padrões os seguintes isolados: EPEC 2348/69; EHEC EDL933; ETEC H1 0407;

25

EIEC 223-83; e EAEC 042. No entanto só foi utilizado neste estudo as linhagens

EAEC e EPEC.

As colônias eae+ e stx- foram pesquisadas para a presença do gene bfpA

(que codifica a pilina da fímbria Bundle Forming Pilus) para a discriminação dos

subgrupos de EPEC (típicas, portadoras de bfpA e atípicas, desprovidas desse

gene).

Também foi empregada neste estudo a pesquisa de outros marcadores de

virulência, que codificam: beta-lactamases de espectro estendido (ESBL), Toxina

citoletal distensora (cdt) e o sideróforo yersiniabactina (irp). Os primers utilizados

estão relacionados na tabela 2.

Para tanto, a extração de DNA foi realizada após crescimento bacteriano em

Agar nutriente por 24 horas a 37ºC, na qual os isolados crescidos foram colocados

em tubos de Eppendorff com água destilada estéril e deixados por 5 a 10 minutos

em água em ebulição.

O DNA foi verificado através do sistema de eletroforese horizontal submerso.

A concentração do gel utilizado variou entre 1% a 2,5%. A agarose foi infundida em

tampão Tris-borato EDTA (TBE) 0,5X, resfriada e vertida em uma cuba contendo

sobre a mesma um pente de acrílico para a formação das canaletas.

Após o endurecimento, o gel foi transferido para a cuba de eletroforese

horizontal submarina contendo tampão TBE 0,5X e as amostras de DNA aplicadas

nas canaletas. A voltagem utilizada foi de 70V.

Após o término da corrida, o gel foi transferido para cuba contendo solução

de brometo de etídio (2,5µg/ml) e o DNA foi visualizado sob luz violeta.

26

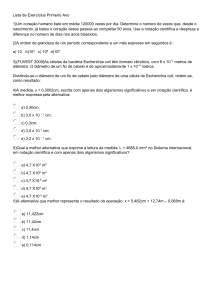

Tabela 2. Primers usados para identificar deiferentes fatores de virulência de Escherichia coli enteroagregativa e

enteropatogênica.

Gene

Fator de virulência

aggR

Fator de transcripção

cdt

toxina distensora citoletal

bfpA

Bundle-forming pili

eae

Intimina

elt

toxina termo lábil

est

Toxina termo estável

set1A

Shigella enterotoxin-1

stx

Verotoxina

irp2

yersinabactina

bla

TEM

bla

CTX-M

Beta-lactamses de espectro

estendido

Tamanho de Referência

amplificação

GTATACACAAAAGAAGGAAGC

ACAGAATCGTCAGCATCAGC

GAAARTAAATGGAAYAYAMATGTCCG

AATCWCCWRSAATCATCCAGTTA

ATTGAATCTGCAATGGTGC

ATAGCAGTCGATTTAGCAGCC

CCCGAATTCGGCACAAGCATAAGC

CCCGGATCCGTCTCGCCAGTATTCG

TCTCTATGTGCATACGGAGC

CCATACTGATTGCCGCAAT

TTAATAGCACCCGGTACAAGCAGG

CCTGACTCTTCAAAAGAGAAAATTAC

TCACGCTACCATCAAAGA

TATCCCCCTTTGGTGGTA

GAGCGAAATAATTTATATGTG

TGATGATGGCAATTCAGTAT

AAGGATTCGCTGTTACCGGAC

254

466

461

881

322

147

309

518

264

TCGTCGGGCAGCGTTTCTTCT

TCGCCGCATCACACTATTCTCAGAATGA

445

ACGCTCACCGGCTCCAGATTTAT

ATGTGCAGYACCAGTAARGTKATGGC

593

TGGGTRAARTARGTSACCAGAAYCAGCGG

(TOMA et

al., 2003)

(TOTH et

al., 2003)

(ROBINSBROWNE

et al., 2004)

(TOMA et

al., 2003)

(TOMA et

al., 2003)

(TOMA et

al., 2003)

(VILA et al.,

2000)

(TOMA et

al., 2003)

(CZECZULI

N et al.,

1999)

(MONSTEI

N et al.,

2007)

(MONSTEI

N et al.,

2007)

27

bla

SHV

ATGCGTTATATTCGCCTGTG

747

TGCTTTGTTATTCGGGCAAA

AAGGTGTTACAGAGATTA

268

efa1

Fator de aderência da EHEC

hlyEHEC

Enterohemolisina

GCATCATCAAGCGTACGTTCC

534

iha

Adesina homóloga a irgA

AATGAGCCAAGCTGGTTAAGCT

CAGTTCAGTTTCGCATTCACC

GTATGGCTCTGATGCGATG

1305

TGAGGCGGCAGGATAGTT

(MONSTEI

N et al.,

2007)

(NICHOLL

S, GRANT,

ROBINSBROWNE,

2000)

(PATON,

PATON,

1998)

(TOMA et

al., 2004)

28

4.3. Detecção da atividade hemolítica

4.3.1. Pesquisa da atividade hemolítica em meio sólido

Para a pesquisa de hemolisina em ágar sangue as linhagens de

Escherichia coli foram cultivadas em infusão de cérebro e coração (BHI) a 37°C

por 24 h em cultivo estacionário. Após o crescimento bacteriano,as linhagens

foram semeadas sobre e em profundidade em ágar Muller Hinton contento 5%

de hemácias: humana (A,B e O), carneiro e cavalo lavadas com tampão fosfato

salina (PBS) com ph de 7,4 (BEUTIN et al., 1988). A título de comparação foi

utilizado estes tipos sanguíneos sem a utilização de PBS. A presença de halos

de hemólise ao redor ou sob as colônias foi observada após 3, 6 e 24 h. Como

controle positivo foi utilizada a linhagem de Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

4.3.2. Pesquisa da atividade hemolítica no sobrenadante da cultura

Alíquotas de 500µL de sobrenadante das culturas de Escherichia coli

em BHI a 37°C foram centrifugadas três vezes (3000 Xg,15 min), sendo

diluídas na razão 2, em PBS com ph 7,4. Uma alíquota de 500 µL de

suspensão a 1% de hemácias de carneiro, previamente lavadas três vezes em

PBS com ph 7,4, foi adicionada a cada orifício contendo os sobrenadantes dos

cultivos bacterianos. Foi incubado à 37°C por uma hora para posterior análise

por espectrofotometria com densidade óptica de 540nm (BHAKDI et al., 1986).

29

4.3.3. Pesquisa de hemólise de contato

As bactérias foram lavadas duas vezes e suspendidas em PBS com ph

7,4 para uma concentração de 2 X 1010 CFU/ml. O contato íntimo entre a

bactéria (50μl) e solução de eritrócitos a 1% (50μl) foi realizado por

centrifugação a 3000 Xg por 20 minutos. Então incubou-se a 37ºC por 3 horas.

Após este período adicionou-se 120μl de PBS frio e centrifugou-se a 2200 Xg

por 20 minutos. 100μl de cada sobrenadante foram transferidos para

microplaca. Densidade óptica a 540nm foi medida por espectrofotometria

(SANSONETTI et al., 1986).

4.4. Infulência da presença de íons, quelantes, protetores osmósticos e

soro na atividade da hemolisina

4.4.1. Cultivo na presença de agentes quelantes e íons

Para verificar a influência de agentes quelantes as linhagens de

Escherichia coli foram cultivadas em BHI contendo separadamente os

quelantes etilenodiamina-tetra ácido acético (EDTA) a 10mM e etileno-di (ohidroxifenol) ácido acético (EDDA) na concentração de 12,5 µg/ml (BHUIYAN,

RAHMAN, HAIDER, 1995).

As amostras também foram crescidas na presença de cloreto de ferro,

cloreto de níquel, cloreto de magnésio, cloreto de cálcio nas concentrações de

10mM. Estes testes foram realizados tanto em placa como em meio líquido,

vistos em 4.3.1. e 4.3.2. respectivamente.

30

4.4.2. Teste de hemólise com protetores osmóticos

Este experimento foi realizado segundo a metodologia descrita por

Bhakdi et al (1986) com algumas modificações. A atividade da hemolisina foi

testada com suspensão de carneiro (1%) em PBS contendo 30mM dos

seguinte carboidratos: frutose, galactose, sacarose e rafinose.

4.4.3. Inibição da atividade hemolítica por soro

A hemolisina foi incubada a 37°C por 30 min na presença de soro

humano normal na razão 2 em PBS. A atividade hemolítica foi testada em

microplaca (item 4.3.2) imediatamente após este tratamento.

4.5. Produção de biofilme

4.5.1. Produção de biofilme em Ágar Vermelho Congo

Meio de cultura constituído de caldo infusão cérebro-coração 37g/L,

sacarose 50g/L, ágar 10g/L e corante Vermelho Congo 0,8g/L. O corante

vermelho

Congo

foi

preparado

como

solução

aquosa

concentrada,

autoclavado separadamente a 121°C por 15 minutos, sendo adicionado ao

ágar quando

este atingiu

a temperatura de 55ºC. Os isolados foram

semeados sobre o meio por esgotamento com alça bacteriológica, incubados

em aerobiose a 35-37°C por 24 horas e após, deixados em temperatura

ambiente por mais 18 horas. As amostras que apresentaram colônias quase

enegrecidas foram consideradas como produtores moderados de biofilme e

colônias negras foram considerados como fortes produtores de biofilme

(FREEMAN, FALKINER, KEANE, 1989).

31

4.5.2. Produção de biofilme em microplaca

Realizado através dos cultivos em BHI, 24 horas após a inoculação a

37ºC. Logo após, uma porção de cada cultivo foi diluída à 1:40 em meio BHI

estéril. Cada amostra, já padronizada, foi adicionada em placas de cultura de

tecido com 96 cavidades com fundo em “U”, em triplicata, junto com controles,

no volume de 200 µL/cavidade. Após preenchidas, as placas foram incubadas

à 37°C por 24h em estufa microbiológica. Passado o tempo de incubação, as

placas foram lavadas por três vezes com tampão PBS com ph 7,4, e deixadas

secar à temperatura ambiente. Nas placas secas adicionou-se Cristal Violeta

200 µL /cavidade por 15 min à temperatura ambiente. Após, cada cavidade foi

lavada com água destilada estéril por três vezes, e deixadas secar à

temperatura ambiente. As placas coradas com cristal violeta foram submetidas

a espectrofotometria

com filtro de 470ηm para aferir as respectivas

absorbâncias de cada cavidade. Baseando-se nas densidades ópticas (D.O.i)

produzidas pelos isolados, e tomando-se por base o controle negativo (D.O.c)

os isolados foram classificados nas seguintes categorias (STEPANOVIC et al.,

2004):

•

Não produtor: D.O.i < D.O.c

•

Produtor Fraco: D.O.c < D.O.i ≤ (2X D.O.c)

•

Produtor Moderado: (2X D.O.c) < D.O.i ≤ (4X D.O.c)

•

Produtor Forte: (4X D.O.c) < D.O.i

32

4.6. Identificação de fímbrias

4.6.1. Identificação da fímbria curli

A cultura foi crescida a 37ºC no meio Luria Bertani (LB), com ph 8,

durante 24 horas. Depois de crescido a cultura foi semeada em placas de LB

(sem sal) contendo 0.004% de Vermelho Congo e 0.002% de Azul Brilhante. As

placas foram incubadas por 24 a 48 horas em temperatura ambiente. Colônias

vermelhas ou rosas são indicativas de bactérias produtoras de curli (DA RE,

GHIGO, 2006).

4.6.2. Identificação da fímbria tipo I

Realizado através dos cultivos em BHI por 24 horas a 37ºC. Logo após,

uma porção de cada cultivo foi centrifugada três vezes (3000xg por 15

minutos), sempre descartando o sobrenadante e colocando PBS com ph 7,4.

Cerca de 500µl dos isolados foram misturados, em lamínulas de vidro, com

500µl de sangue lavado três vezes com PBS, com e sem adição de manose.

As amostras que produziram hemaglutinação, somente, na ausência de

manose foram consideradas positivas para fímbria tipo I (CLEGG, OLD, 1979).

4.7. Resistência ao soro

Para identificar os isolados de E. coli resistentes ao soro foi seguida a

seguinte metodologia (PELKONEN, FINNE, 1987), com algumas modificações.

Foi obtido soro humano na coleta de sangue de 10 adultos imunocompetentes.

O soro foi congelado a -86ºC até o uso.

Foram obtidas três formas de soro a serem desafiados contra os

isolados em análise: 1) soro inativado, considerando sem atividade do sistema

33

complemento, obtido por incubação por 30 minutos a 56ºC; 2) soro tratado com

Etilenodiamina-tetra ácido acético (EDTA) na concentração de 10mM, para

inibir a atividade do complemento pela via clássica e alteranativa e por último;

3) soro normal sem quaisquer tratamento.

Após a reativação dos isolados em caldo de infusão de cérebro e

coração (BHI), 500µl de cada cultura foram adicionados a 4,5ml de BHI, e

incubados por 90 minutos a 37ºC. Após esta etapa, as culturas foram

centrifugadas a 1500Xg por 15 minutos. O sobrenadante foi descartado e três

ml de PBS ph 7,4 foram adicionados para ressuspender o sedimento.

A resistência ao soro foi analisada usando placas de microtitulação em

fundo chato por espectrofotometria. Para a realização do teste 120µl de PBS

foram colocados nos primeiros dois orifícios da microplaca e 120µl da

suspensão bacteriana nos subseqüentes.

Foram adicionados 60µl de soro, para uma concentração final de 33%

nos orifícios da microplaca, sendo incubada a 37ºC. A absorbância em

comprimento de onda de 470ηm foi mensurada nos seguintes tempos após a

adição do soro: 0, 30, 60, 90 e 120 minutos. Cada isolado foi testado em

triplicata para soro normal, tratado com EDTA e soro inativado. O isolado que

reduziu a absorbância inicial para valores inferiores a 50% foi considerado

sensível. Foram considerados resistentes os isolados que apresentaram fração

sobrevivente superior a 90%, e os que ficaram entre estes dois valores foram

considerados intermediários.

34

4.8. Teste de resistência aos antimicrobianos

O teste de resistência aos antimicrobianos foi realizado segundo a

metodologia de difusão com discos (BAUER et al., 1966). As culturas obtidas

foram diluídas em escala seriada decimal até atingir a concentração estimada

de 3X105 UFC/ml. Em seguida, com auxílio de um “swab” estéril, uma alíquota

da cultura foi espalhada sobre toda superfície das placas Petri contendo 50ml

de Müller-Hinton, para se obter um inoculo uniforme e homogêneo. Após dois

minutos, discos de antimicrobianos foram posicionados na superfície do ágar

em posições eqüidistantes, e as placas foram incubadas a 37ºC por 18 horas.

Após incubação, os diâmetros dos halos de inibição do crescimento foram

mensurados. Para interpretação das medidas dos halos, foram considerados

os padrões de resistência e sensibilidade para bactérias Gram-negativas do

Clinical and LaboratoryStandards Institute. Foram utilizados os seguintes

antibióticos: ampicilina (10μg), cefalotina (30μg), ceftazidima (30μg), ampicilina

+ sulbactam (10/10μg), sulfametaxazol + trimetoprim, tircacilina + ácido

clavulânico (75/10μg), cefuroxima (30μg), imipenem (10μg), aztreonam (30μg),

piperacilina + tazobactam (100/10μg), gentamicina (10μg), ceftriaxona (30μg).

4.9. Análise estatística

Para análise de resistência ao soro foi utilizado ANOVA. Na avaliação

da presença dos fatores de virulência e as respectivas combinação entre os

fatores de virulência, empregou-se regressão logística múltipla. Já a

associação da presença de algum gene codificador de beta-lacatamase de

espectro estendido e resistência a vários tipos de antibióticos, foi empregado

35

coeficiente

de

Contingência C.

estatisticamente significativo.

O

valor de

p<0,05 foi

considerado

36

5. RESULTADOS

5.1. Detecção da atividade hemolítica

5.1.1. Pesquisa de hemolisina

Das

19

amostras

de

Escherichia

coli

examinadas,

4

(21%)

apresentaram halo de hemólise ao redor das colônias em meio sólido. A

presença de halo começou a evidenciar-se após 6 horas, em dois isolados, e

24 horas de incubação nos outros dois isolados hemolíticos (tabela 3).

Foi visualizado hemólise em todos os tipos de sangue, exceto por um

isolado que não apresentou atividade hemolítica no sangue humano tipo B e

outro em sangue de cavalo, o que não representou diferença da atividade

hemolítica para o tipo de sangue utilizado (p>0,05). O meio preparado com

hemácias

lavadas

não

alterou

o

padrão

de

hemólise

(dados

não

demonstrados). Quando testou-se o íntimo contato dos isolados hemolíticos

com eritrócitos de carneiro verificou-se que o isolado A19 apresentou hemólise

total (99%) e os isolados A 15 e A 18 apresentaram hemólises similares,72% e

73% respectivamente. Apenas o isolado A 11 não apresentou tal atividade

(dados ao demonstrados).

37

Tabela 3 . Expressão de hemolisina de Escherichia coli em placas de MullerHinton-sangue, com diferentes hemácias, observada em diferentes tempos

(horas) de cultivo.

Humano

Carneiro

Cavalo

Linhagem

Identificação

O

B

3 6 24 3 6 24 3 6 24 3 6 24

EAEC

A 16

- - - - - - - A 14

- - - - - - - A5

- - - - - - - A 19

- - + - +

- - - +

A 17

- - - - - - - A7

- - - - - - - A 10

- - - - - - - A2

- - - - - - - A 15

- + + - +

- +

+ - + +

A9

- - - - - - - A3

- - - - - - - EPEC atípica

A6

A 18

A4

A1

A 12

A 13

A 11

A8

-

+

-

+

+

-

-

-

+

+

-

-

+

-

+

+

-

-

-

+

-

5.1.2. Influência de diferentes condições de cultivo na atividade

hemolítica

O quelante de ferro (EDDA), cloreto de ferro e cloreto de cálcio não

alteraram a atividade hemolítica das amostras analisadas, entretanto a

presença d o quelante de cálcio (EDTA) inibiu esta atividade quando testados

em meio sólido (tabela 4). Deste modo pode-se notar que a constituição do

meio interfere na atividade hemolítica (p<0,05).

O mesmo foi observado

quando os isolados foram testados em meio líquido, como demonstrado na

figura 1. Verificou-se que a atividade hemolítica no meio de cultura acrescido

de EDDA

e cálcio foi maior com média de 84% e 81% respectivamente,

38

apresentando valores similares ao meio de cultura puro (p>0.05). Os meios de

cultura acrescidos de níquel, magnésio e ferro apresentaram atividade

hemolítica com índices menores que meio puro, com média de 66%, 54%,

65%, respectivamente. Entretanto tal diminuição não apresentou diferença

estatisticamente significativa (p>0.05).

Por outro lado, observou-se que o acréscimo de EDTA ao meio de

cultura causou uma diminuição da atividade hemolítica (29% de hemólise) em

relação ao meio de cultura puro. Entretanto no que diz respeito do tipo de

linhagem, EPEC atípica e EAEC, e a constituição do meio, demonstrou-se que

não há interferência destes fatores com a atividade hemolítica (p>0.05), como

demonstrado na tabela 4. Dos carboidratos utilizados nenhum efetivamente

protegeu contra atividade hemolítica.

39

Tabela 4. Atividade hemolítica de isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica em sangue de carneiro

com diferentes constituintes de cultivo

Quelantes

Íons

Linhagem Identificação EDTA EDDA Fe3+ Ca2+

EAEC

A 16

A 14

A5

A 19

+

+

+

A 17

A7

A 10

A2

A 15

+

+

+

A9

A3

EPEC

atípica

A6

A 18

A4

A1

A 12

A 13

A 11

A8

-

+

+

-

+

+

-

+

+

-

Carboidrato (Diâmetro molecular em nm)

Fru

Gal

Sac

Raf

(0,72)

(0,72)

(0,9)

(1,2 - 1,4)

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

-

EDDA - Etileno-di (o-hidroxifenol) ácido acético; EDTA - Etilenodiamina-tetra ácido acético. Fru- frutose; Gal Galactose; Sac - sacarose; Raf - rafinose

40

5.2. Produção de biofilmes

Dependendo da metodologia empregada, houve variação entre as

categorias dos isolados categorizados como produtores de biofilme, mas estes

métodos se apresentam similares (p>0,05). Pode ser visto na tabela 5, que

31% dos isolados analisados por Ágar Vermelho Congo não foram produtores

de

biofilme,

freqüência

relativa

maior

que

na

metodologia

por

espectrofotometro.

Segundo o método em microplaca, aproximadamente 26% não foram

produtores de biofilme; 37% se apresentaram como fortes produtores, 10%

moderados produtores e 26% foram considerados como fracos produtores de

biofilme, como pode ser visto na figura 2.

41

5.3. Identificação de isolados produtores de fímbrias: curli e

fímbria tipo I

Dos isolados testados apenas 4 (21%) não apresentaram a fímbria

curli, sendo todos pertencentes a linhagem EAEC. Contudo apenas esta

linhagem apresentou fímbria tipo I (3 amostras).

Não houve associação entre a presença da fímbria curli com a

produção nem com o grau de produção de biofilme (p>0,05).

42

Tabela 5. Presença de curli, Fímbria tipo I e Produção de Biofilme entre os isolados de

EAEC e EPEC atípica

Biofilme*

Linhagem

Identificação

EAEC

EPEC atípica

Hemaglutinação

curli

AVC

ESP

HMR

HMS

A 16

++

++

-

-

+

A 14

+++

+++

+

-

-

A5

++

-

+

-

+

A 19

+++

+++

-

-

+

A 17

+++

+++

+

-

-

A7

++

+

-

+

+

A 10

-

-

-

+

+

A2

+++

-

+

-

-

A 15

-

-

-

-

-

A9

+++

+

-

+

+

A3

-

+

-

-

+

A6

+++

+

-

-

+

A 18

+++

+++

+

-

+

A4

++

+++

+

-

+

A1

+++

+

+

-

+

A 12

++

++

-

-

+

A 13

-

-

+

-

+

A 11

-

+++

+

-

+

A8

-

+++

+

-

+

AVC - Ágar Vermelho Congo; ESP - espectofotometria; HMR - hemaglutinação manose resistente; HMS hemaglutinação manose sensível (fímbria tipo I). * - = não produtor de biofilme; + = biofilme fraco; ++ =

Biofilme moderado; +++ = Biofilme forte.

5.4. Caracterização dos marcadores de virulência e presença de

beta-lactamases de espectro estendido entre os isolados

Na análise genotípica, realizada pela técnica PCR, acerca da

distribuição de ESBL (Tabela 6), notou-se que os isolados de EAEC

apresentaram uma freqüência relativa altíssima para algum gene responsável

43

pela produção de beta-lactamase (72%), enquanto os isolados de EPEC atípica

essa presença teve uma leve diminuição (50%). É importante ressaltar que o

gene mais prevalente foi o

bla

TEM, presente em sete isolados de EAEC e três

em EPEC atípica (53%); acompanhado do

bla

CTX-M, 2 em EAEC e 1 em EPEC

atípica (16%).

Tabela 6. Distribuição de beta-lactamases de espectro estendido

(ESBL) entre os isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica.

ESBL

Linhagem

EAEC

Identificação Laboratorial

A2

A 19

A3

A 16

A7

A 10

A5

A 17

A 15

A 14

A9

EPEC atípica

A4

A1

A 12

A6

A 18

A 11

A8

A 13

bla

CTX-M

+

+

+

-

bla

TEM

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

bla

SHV

-

Em contraposição que estes achados, a distribuição de marcadores de

virulência, vistos na tabela 7, se mostrou tímida; haja visto que somente duas

amostras (10%) apresentaram sideróforo yersiniabactina e uma (5%) a adesina

iha, todas pertencentes a EPEC atípica. Apenas uma amostra apresentou a

combinação de gene responsável pela produção de beta-lactamases e um

44

marcador de virulência (irp e

bla

TEM). Vale ressaltar que todos os isolados de

EPEC atípica foram considerados como atípicos devido a ausência do

marcador bfp.

Tabela 7. Distribuição de marcadores de virulência entre Escherichia coli

enteroagregativa e enteropatogênica atípica.

Adesinas

Toxina

Sideróforo

Identificação

bfp efa-1 iha cdt hlyEHEC

irp

Linhagem

Laboratorial

EAEC

A2

A 19

A3

A 16

A7

A 10

A5

A 17

A 15

A 14

A9

EPEC atípica

A4

A1

A 12

A6

A 18

A 11

A8

A 13

-

-

+

-

-

-

+

+

bfp – bunding forming pilus; cdt – citolethal distending toxin; irp- Yersiniabactin biosynthesis

gene, efa-1- EHEC fator para aderência; iha –adesina homóloga a irgA;

ehx enterohemolisina.

5.5. Resistência aos antimicrobianos

Embora o teste de fenotipagem da suscetibilidade dos isolados de E.

coli demonstrar que cerca de 42% dos antibióticos foram eficazes em inibir o

crescimento de todos os isolados testados, 40% destes eram beta-lactâmicos

associados com protetores contra a ação das enzimas beta-lactamases

(Tabela 8).

45

Como pode-se notar nos dados mencionados no item anterior, e que

comprova-se com o teste fenotípico, a ação das beta-lactamases conferem

resistência aos isolados. Isto é demonstrado na tabela 8, na qual houve

diminuição da freqüência relativa de isolados resistentes a ampicilina quando

comparados com este medicamento em associação com com sulbactam,

protetor da ação das beta-lactamases, 58% para 0% respectivamente (p<

0.05).

Por outro lado não foi possível determinar qualquer correlação entre a

presença dos genes responsáveis pela produção de beta-lactamases e o tipo

de antibiótico ao(s) qual(is) era(m) resistente(s) (p>0,05), o que pode denotar

uma possível heterogenicidade ou, melhor ainda, presença de algumas

subclasses destas enzimas para o determinado gene encontrado.

46

Tabela 8. Perfil de sensibilidade a antimicrobianos dos isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica.

Antibióticos

Identificação

Linhagem

laboratorial AMP KF CAZ SAM SXT TIM CXM IPM ATM TZP CN CRO

EPEC atípica A1

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

I

S

A4

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

A6

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

R

S

A8

A11

A12

A13

A18

S

R

S

S

R

R

R

R

R

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

I

R

S

S

R

R

S

S

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

I

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

EAEC

A2

S

R

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

A3

R

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

A5

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

A7

R

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

A9

I

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

A10

I

R

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

A14

S

I

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

A15

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

R

S

A16

R

R

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

A17

R

R

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

A19

R

R

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

AMP – ampicilina; KF – cefalotina; CAZ – ceftiazidima; SAM – ampicilina +

sulbactam; SXT – sulfametaxazol + trimetoprim; TIM – tircacilina + ácido

clavulânico; CXM – cefuroxima; IPM – imipenem; ATM – aztreonam; TZP –

piperaciclina + tazobactam; CN – gentamicina; CRO – ceftriaxona. S –

sensível; I – indeterminado; R – resistente.

Interessante notar que os isolados positivos para algum tipo de gene

responsável pela produção de beta-lactamases, avaliados neste estudo,

apresentaram ampla resistência a vários tipos de antibióticos quando,

comparados aos não produtores (tabela 7 e 8), principalmente pela presença

do gene

bla

TEM, já que 38% dos isolados que apresentavam tal gene tiveram

um perfil de resistência em três ou mais tipos de antibióticos testados.

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

R

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

47

5.6. Resistência ao soro

Pode-se verificar nas figuras 3A, 3B e 3C; que as taxas de crescimento

entre os isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica não diferem nos soros analisados

(humano normal, soro tratado com EDTA e no soro inativado por aquecimento),

tão pouco há diferença entre os períodos de incubação (p> 0.05).

Contudo há diferença da taxa de crescimento no soro humano normal

(figura 3A) com os outros dois analisados (figuras 3B, 3C), tanto nos isolados

de EAEC quanto nos isolados de EPEC atípica (p<0.05). Isto é corroborado

com a constatação de que apenas um isolado (5%) foi considerado sensível,

sendo pertencente a linhagem EPEC atípica; quatro (21%) intermediários, uma

EPEC atípica e três EAEC; e 14 (74%) resistentes a ação do soro humano

normal in vitro (figura 3A).

No soro tratado com EDTA (figura 3B), pode-se notar que esta

freqüência foi alterada, já que 18 (95%) dos isolados foram considerados

resistentes, com sua taxa de crescimento sendo influenciada pela ausência de

atividade da via clássica e alternativa do sistema complemento (p<0,05).

No entanto os isolados tidos como resistentes tiveram um maior

crescimento no soro humano normal que no soro tratado com EDTA (p<0,05).

As curvas de crescimento das cepas no soro tratado com EDTA e no soro

inativado foram similares (p>0,05), apesar dos primeiros 30 minutos de

incubação o crescimento dos isolados em soro com EDTA foi bem superior

(dados não demonstrados).

É importante mencionar que nem a presença de produtores fortes de

biofilme nem a presença da fímbria curli tiveram associação com esta

resistência (p>0,05).

48

49

5.7. Prevalência entre marcadores e fatores de virulência dos

isolados de EAEC e EPEC atípica

A distribuição dos diferentes fatores de virulência foi bastante

heterogênea, com 12 (63%) isolados apresentando quatro ou mais fatores de

virulência. Neste estudo, a mais frequente combinação foi: produção de

biofilme, curli, resistência ao soro (15,7%);

resistência ao soro (10,5%);

bla

CTX, produção de biofilme, curli,

bla

TEM, produção de biofilme, curli, resistência ao

soro e hemólise (10,5%); blaTEM, curli, resistência ao soro (10,5%) (tabela 9).

Pode-se notar, também, que as cepas de EAEC não apresentaram

repetição aos mesmos fatores em isolados diferentes, ao contrário do que pode

ser visto nas cepas de EPEC atípica (dois isolados). Não houve associação

entre o tipo de linhagem e a presença de algum destas propriedades de

virulência (p>0,005).

É importante salientar que as cepas hemolíticas foram as mais

virulentas, pois as mesmas apresentaram pelos menos cinco dos 11 fatores e

marcadores de virulência testados, sempre apresentando produção de biofilme

e resistência ao soro, além de três entre as quatro cepas hemolíticas são

produtoras de β-lactamases de espectro estendido.

50

Tabela 9. Frequência relativa e absoluta dos fatores de virulência,

marcadores e genes responsáveis pela produção de beta-lactamases de

espectro estendido (ESBL).

EAEC nº

EPEC atípica nº

Total nº

Fatores de Virulência

(%)

(%)

(%)

Resistência ao soro

8 (72,7%)

6 (75%)

14 (73,6%)

Biofilme

9 (81%)

6 (75%)

15 (78%)

curli

7 (63,6%)

8 (100%)

15 (78%)

Fímbria tipo I

3 (27,2%)

0 (0%)

3 (15,7%)

Hemólise

2 (10,5%)

2 (25%)

4 (21%)

Marcadores de virulência

irp

0 (0%)

2 (25%)

2 (10,5%)

iha

0 1 (12,5%)

1 (5,25%)

ESBL

bla

TEM

7 (63,3%)

3 (37,5%)

10 (52,6%)

bla

CTX-M

2 (10,5%)

1 (12,5%)

3 (15,7%)

51

6. DISCUSSÃO

Escherichia coli tem se destacado como um importante agente de

diarréia infecciosa, principalmente em crianças. A patogenicidade das

linhagens diarreiogênicas está possivelmente associada a diversos fatores de

virulência, por exemplo, produção de biofilme, expressão de fímbrias, produção

de hemolisinas, resistências antimicrobianos e ao soro (ELIAS et al., 2002;

TRABULSI et al., 2002).

A adesão e, posterior, produção de biofilme tem sido demonstrado

como sendo um fator primordial para que uma linhagem bacteriana inicie sua

infecção. A habilidade para formar biofilme está intimamente relacionadas à

persistência e virulência bacteriana (FERRIERES et al., 2007a; HARRISON et

al., 2009).

A adesão pode ser realizada através de diversas fímbrias, dentre elas o

curli que tem um importante papel na patogenicidade. Sugere-se que a fímbria

curli tem a função de promover a autoagregação entre bactérias, além de

facilitar invasão e colonização (DYER et al., 2007). Outros estudos realizados

demonstraram que as cepas que possuíam tal estrutura eram mais virulentas

que cepas que não possuíam (UHLICH, KEEN, ELDER, 2002; UHLICH,

COOKE, SOLOMON, 2006).

Entretanto constatou-se que não houve relação da produção de

biofilme com a expressão da fímbria tipo I e a curli pois apesar de 73% dos

isolados estudados produzirem biofilme, somente três isolados apresentaram

somente fímbria tipo I e fímbria curli (pertencentes a linhagem EAEC) e doze

apresentaram somente fímbria curli (8 EPEC atípicas e 4 EAEC). Os resultados

52

sugerem, também, que a presença de outras fímbrias pois dez cepas

analisadas apresentaram hemaglutinação manose resistente.

Quanto à produção de hemolisina, várias pesquisas concluíram que

isolados que apresentavam a capacidade de produção desta toxina eram

visivelmente mais virulentas do que os isolados não-hemolíticos (COOKSON et

al., 2007; HUNT et al., 2008).

Tais dados são confirmados neste estudo, já que todos os quatro

isolados com atividade hemolítica apresentaram o maior número de

propriedades de virulência em relação às outras cepas. Estes isolados

apresentaram resistência ao soro, com média de 134%, demonstraram genes

codificadores de beta-lactamases, e uma atividade hemolítica de contato com

características diferentes da enterohemolisina. Este fato pode ser comprovado

pela não amplificação do gene responsável pela produção da enterohemolisina

bem como, testes fenotípicos pois não houve diferenciação na a expressão da

hemolisina de contato na presença de sangue lavado e não lavado.

A enterohemolisina é mencionada por alguns autores como uma

enterotoxina, relacionada com hemolisina, codificada pelo mesmo plasmídio

responsável bundle-forming fimbriae, no qual é associado com a aderência

agregativa da EAEC, na qual ela só é liberada no meio externo após íntimo

contato entre a bactéria e o eritrócito (BALDWIN et al., 1992; NATARO et al.,

1992; HAQUE et al., 1994)

A análise da presença de diferentes constituintes no meio de cultura

para detectar interferências na ação da hemolisina, verificou-se que o uso de

quelante de ferro (EDDA) e cloreto de cálcio foram capazes de aumentar a

atividade hemolítica, ao contrário do uso de EDTA, que inibiu tal atividade. Esta

53

última característica demonstra uma propriedade da α-hemolisina, já que esta

necessita do cálcio para a estabilização e formação de poros em membranas

biológicas (DOBEREINER et al., 1996; VALEVA et al., 2008). Pode ser visto

também que o soro não afetou a ação da hemolisina, pois não houve diferença

deste com o meio de cultura puro.

De outro lado, os meios com íons níquel e magnésio diminuíram a ação

da hemolisina. Estes dados corroboram com os achados de outro estudo, na

qual faz menção que cátions divalentes apresentam um efeito ambíguo na

ação desta toxina (DOBEREINER et al., 1996).

Uma das prováveis explicações para o fato seria que outros cátions

não suportam a atividade lítica da toxina e não se ligam a resíduos da

hemolisina dentro da região formadora do poro (SCHINDEL et al., 2001). De

outro lado, como a hemolisina não apresenta um receptor específico e meios

alcalinos apresentam pequena quantidade de cálcio em sua composição a

redução da hemólise não foi tão drástica quanto a observada no meio tratado

com EDTA.

Uma característica

patogênica importantíssima à virulência de

linhagens de E. coli, associada a atividade hemolítica, é a capacidade de

produção de sideróforo. Esta estrutura possibilita que as bactérias obtenham

ferro, necessário a sua sobrevivência, a partir das células do hospedeiro.

Recentes estudos têm demonstrado que algumas cepas patogênicas de

Escherichia coli apresentam ilhas de patogenicidade originalmente encontradas

em Yersinia spp que codificam o sideróforo yersiniabactina (KOCZURA,

KAZNOWSKI, 2003; HANCOCK, FERRIERES, KLEMM, 2008).

54

Os resultados da análise dos 19 isolados de Escherichia coli

demonstraram que dentre estas, 2 apresentaram yersiniabactina. Se dentre

estas linhagens que apresentaram tal propriedade, apenas um isolado tinha

atividade hemolítica, o que diverge destes estudos mencionados acima.

Um mecanismo importante para a sobrevivência dos microorganismos

no hospedeiro é a de burlar as linhas de defesa do sistema imunológico. Estes

agentes têm usado várias estratégias com esta finalidade como atividade

hemolítica e leucotóxica, expressão de proteína M, antígeno O do

lipossacarídeo, cápsula contendo resíduos de ácido sialicílico e a captura de

inibidores do sistema complemento para então inativá-lo (MUSHTAQ et al.,

2004; WOOSTER et al., 2006; MARUVADA, BLOM, PRASADARAO, 2008).

Como pode ser visto neste trabalho, a maioria dos isolados testados

foram resistentes a incubação com soro humano normal. Interessantemente as

cepas que apresentaram uma sobrevivência acima de 90% em duas horas de

incubação. Uma das justificativas, para esses dados, seria que os isolados de

E. coli resistem a atividade bactericida do soro mais eficientemente devido a

diminuição da deposição de proteínas do sistema complemento e subseqüente

formação de complexo de ataque a membrana e lise (MARUVADA et al.,

2008).

Prévios estudos relatam que proteínas de membrana externa da E. coli,

principalmente OmpA, interagem com moléculas do sistema complemento

medeiando a degradação de C3b e C4b, o que culmina na evasão da atividade

bactericida do soro, evitando a via clássica e alternativa do sistema

complemento (PRASADARAO et al., 2002; WOOSTER et al., 2006).

55

Notou-se, também, quando a via alternativa e a via clássica foram

inibidas com a presença de EDTA, os isolados que foram considerados como

resistentes intermediários no soro normal, obtiveram um maior crescimento,

sendo caracterizadas como resistentes. Este dado pode ser explicado pelo fato

de que a ligação da lectina manose-ligante (MBL) à Escherichia coli é

diminuída na presença de EDTA (SHIRATSUCHI et al., 2008). Contudo esta

via necessita do componente C4 e, como foi visto acima, esta bactéria

apresenta mecanismos para burlar este caminho.

Outra forma importante de sobrevivência bacteriana é demonstrada

pela

resistência

susceptibilidade

a

a

antimicrobianos.

ampicilina

e

Este

estudo

trimetoprim

foi

demonstrou

apreciável

e

que

a

que

a

multiressistência (resistência a mais de 3 antibióticos) foi presente em 26% dos

isolados.

Quanto a presença de genes responsáveis pela produção de betalactamases observou-se uma elevada prevalência nos isolados estudados

(68%). Estes dados são convergentes com dados obtidos no estudo realizado

no Rio Grande do Sul (OLIVEIRA et al., 2009), porém divergente com achados

referentes a países europeus, africanos e asiáticos (BATCHOUN, SWEDAN,

SHURMAN, 2009; PITOUT et al., 2009; USEIN et al., 2009). Contudo estes

estudos abordaram isolados de infecção de vários sítios anatômicos e não

somente de casos de diarreia.

Ainda em relação a presença deste marcador de virulência, pode-se

notar que os isolados como estes genes obtiveram uma maior amplitude de

resistência a antibióticos em relação aos que não apresentaram, tornando a

escolha terapêutica difícil. Tanto EAEC como EPEC atípica se mostraram muito

56

susceptíveis a imipenem, cefuroxima, ceftriaxona e medicamentos associados

com protetores contra a ação de beta-lactâmicos.

Contudo um isolado EPEC atípica se mostrou resistente a ação da

tircacilina associada com ácido-clavulânico,o que denota ação de alguns

subtipos de beta-lactâmicos, já que os demais foram sensíveis (CARATTOLI,

2009; BUSH, JACOBY, 2010).

Pode-se notar, também, que cerca de 58% dos isolados apresentaram

mais de quatro fatores de virulência dos onze analisados. Destes sete foram

representantes da linhagem EAEC e 4 de EPEC atípica, totalizando 63% e

50% entre os isolados da mesma linhagem, respectivamente.

57

7. CONCLUSÃO

Pelo o que foi discutido, verificou-se que os fatores de virulência mais

evidenciados nos isolados de E. coli obtidos de amostra de fezes de crianças

são: resistência ao soro; a expressão da fímbria curli; produção de biofilme;

genes responsáveis pela produção de beta-lactamases.

Em relação a resistência a antimicrobianos, verificou-se que cerca de

61% dos isolados que apresentaram genes para beta-lactamases foram

resistentes a mais de 3 tipos de antibióticos

A forma como os fatores de virulência se apresentaram neste estudo

reflete sua ocorrência ocasional, com perfis dispersos nas duas linhagens

analisadas, excetuando por dois isolados de EPEC atípica que demonstraram o

mesmo perfil de virulência.

Deste modo, não houve associação entre as diversas propriedades

analisadas, contudo as cepas hemolíticas foram as mais virulentas com cinco

propriedades de virulência para cada isolado hemolítico. Pode-se notar,

também, que um isolado de EPEC atípica e EAEC, produtores de hemolisina,

apresentaram a mesma combinação de fatores de virulência analisados. Em

relação a hemolisina, pode-se notar que a melhor atividade se deu na presença

de EDDA e cloreto de cálcio. Em contraste esta ação foi praticamente nula no

meio que apresentava EDTA.

Interessantemente os meio que continham íons de magnésio, níquel,

ferro e soro humano foram similares, quanto à hemólise, ao meio puro. Cabe

salientar que dos quatro isolados com atividade hemolítica no sobrenadante

(exotoxina), três apresentaram atividade hemolítica de contato (endotoxina).

58

8. REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

ALDICK, T., et al. Vesicular stabilization and activity augmentation of

enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli haemolysin. Mol Microbiol, v.71, n.6,

Mar, p.1496-508. 2009.

BALDWIN, T. J., et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains secrete a

heat-labile toxin antigenically related to E. coli hemolysin. Infect Immun, v.60,

n.5, May, p.2092-5. 1992.

BATCHOUN, R. G., S. F. SWEDAN,A. M. SHURMAN. Extended Spectrum

beta-Lactamases among Gram-Negative Bacterial Isolates from Clinical

Specimens in Three Major Hospitals in Northern Jordan. Int J Microbiol,

v.2009, p.513874. 2009.

BAUER, A. W., et al. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single

disk method. Am J Clin Pathology, v.45, n.4, p.493-496. 1966.

BEUTIN, L., et al. Enterohemolysin, a new type of hemolysin produced by some

strains of enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC). Zentralbl Bakteriol, v.267, p.576588. 1988.

BHAKDI, S., et al. Escherichia coli hemolysin may damage target cell

membranes by generating transmembrane pores. Infect Immun, v.52, n.1, Apr,

p.63-9. 1986.