Enviado por

menaribeiro

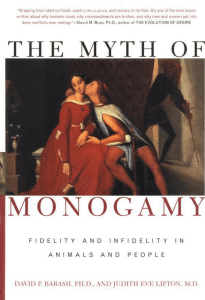

Psychology of sexual response