Enviado por

common.user6546

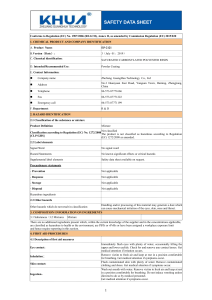

Prep Gdl HazDrugs[1]

![Prep Gdl HazDrugs[1]](http://s1.studylibpt.com/store/data/006262602_1-18605bddd180377984fa8fe398478fc4-768x994.png)