Enviado por

common.user3608

trans bipolar e suícidio

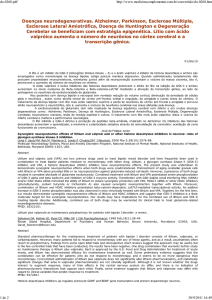

Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Affective Disorders journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jad Research paper Bipolar depression and suicidal ideation: Moderators and mediators of a complex relationship T Masoud Kamalia,b,c, , Noreen A. Reilly-Harringtona,b, Weilynn C. Changa, Melvin McInnisc, Susan L. McElroyd, Terence A. Kettere, Richard C. Sheltonf, Thilo Deckersbacha,b, Mauricio Toheng, James H. Kocsish, Joseph R. Calabresei, Keming Gaoi, Michael E. Thasej, Charles L. Bowdenk, Gustavo Kinrysa,b, William V. Bobol, Benjamin D. Brodyh, Louisa G. Sylviaa,b, Dustin J. Rabideaum, Andrew A. Nierenberga,b a Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States b Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States c d Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati OH and Lindner Center of HOPE, Mason, OH, United States Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, United States e f Department of Psychiatry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States Department of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico Health Science Center, Albuquerque, NM, United States Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States i Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, United States j Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States k Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, United States l Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States g h m Department of Biostatistics, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Bipolar disorder Depression Suicidal ideation Lithium Quetiapine Introduction: Not all patients with bipolar depression have suicidal ideation (SI). This study examines some factors that link bipolar depression to SI. Methods: 482 individuals with bipolar I or II were randomized to either lithium or quetiapine plus adjunctive personalized therapy in a 24 week comparative effectiveness trial. Severity of depression and SI were assessed with the Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale (BISS). We examined potential moderators (age, gender, age of illness onset, bipolar type, comorbid anxiety, substance use, past suicide attempts, childhood abuse and treat-ment arm) and mediators (severity of anxiety, mania, irritability, impairment in functioning (LIFE-RIFT) and satisfaction and enjoyment of life (Q-LES-Q)) of the effect of depression on SI. Statistical analyses were con-ducted using generalized estimating equations with repeated measures. Results: Bipolar type and past suicide attempts moderated the effect of depression on SI. Life satisfaction mediated the effect of depression and SI. The relationship between anxiety, depression and SI was complex due to the high level of correlation. Treatment with lithium or quetiapine did not moderate the effect of depression on SI. Limitations: Suicide assessment was only done using an item on BISS. Patient population was not specifically chosen for high suicide risk. Discussion: Individuals with Bipolar II experienced more SI with lower levels of depression severity. A history of suicide predisposed patients to higher levels of SI given the same severity of depression. Reduced life satisfaction mediates the effect of depression on SI and may be a target for therapeutic interventions. This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ: 1R01HS019371) and the Dauten Family Center for Bipolar Treatment Innovation. Corresponding author at: Dauten Family Center for Bipolar Treatment Innovation, Massachusetts General Hospital, 50 Staniford Street, Suite 580, Boston, MA 02114, United States. E-mail address: [email protected] (M. Kamali). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.032 Received 5 August 2018; Received in revised form 27 July 2019; Accepted 17 August 2019 Available online 19 August 2019 0165-0327/ © 2019 Published by Elsevier B.V. Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 M. Kamali, et al. 1. Introduction concurrent symptoms and stressors would account for a significant portion of the association between SI and depression. Bipolar disorder has high rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and deaths from suicide (López et al., 2001; Slama et al., 2004; Tondo et al., 2003; Valtonen et al., 2005). In clinical studies of bipolar dis-order, 20 to 30% of the participants report suicidal ideation at time of study entry (Goldberg et al., 2005; Suppes et al., 2001). Depressive episodes are common in bipolar disorder, and suicidal ideation (SI) is closely related to depression and one of the diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode. However, not all patients who are depressed experience suicidal ideation. 2. Methods The Bipolar CHOICE study (Comparative Effectiveness of a SecondGeneration Antipsychotic Mood Stabilizer and a Classic Mood Stabilizer for Bipolar Disorder) is a 24 week, multi-site, randomized pragmatic clinical trial comparing lithium to quetiapine. Study rationale, design, methods, and results have been reported elsewhere (Nierenberg et al., 2016, 2014). Briefly, the study enrolled 482 in-dividuals aged 18–70 years, between 2011 and 2012 across 11 sites (Nierenberg et al., 2016). Participants were required to have a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder (determined using an electronic version of the Extended Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [MINI]) (Sheehan et al., 1998) and to be at least mildly symptomatic (defined as a Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale for Bipolar Disorder [CGI-S-BP] ≥3) (Spearing et al., 1997). Demographic data such as age of onset of bipolar disorder, history of suicide attempts and history of childhood abuse were collected at baseline. Participants were randomized to lithium or quetiapine plus adjunctive personalized therapy (APT). This included any additional medications needed for management of symptoms, consistent with guidelines used to treat bi-polar disorder and personalized to the clinical needs of the patient (Suppes et al., 2005). There were few restrictions on treatment options per study protocol other than the lithium arm could not receive anti-psychotics and the quetiapine arm could not receive lithium or other antipsychotics. All other clinically appropriate medication choices for bipolar disorder, including other mood stabilizers such as Valproic acid, Carbamazepine or benzodiazepines were allowed. Clinical variables such as age (Ösby et al., 2001), gender (Baldassano, 2005), age of onset of illness (Slama et al., 2004), type of bipolar disorder (I vs. II) (Coryell et al., 1987; Novick et al., 2010; Tondo et al., 2007), history of childhood abuse (Garno et al., 2005), comorbid substance abuse disorders (Tondo et al., 1999), anxiety (Simon et al., 2007), mixed mood states (Balázs et al., 2006), poorer quality of life (Chen et al., 2011; de Abreu et al., 2012), and functional impairment (Sanchez-Moreno et al., 2009) have been reported as fac-tors increasing the risk of suicidal behavior. Certain variables such as gender or type of bipolar disorder may have differential effects on how depressed mood leads to SI. Likewise, co-occurring symptoms of irrit-ability or anxiety may mediate the effects of depression on SI. Also, an important clinical question is if lithium, compared to quetiapine, has an independent effect on suicidal ideation, above and beyond its effects on mood. Prior research has suggested that lithium has independent effects on reducing suicide that are distinct from its effectiveness as a treat-ment for mood disorders (Ahrens and Müller-Oerlinghausen, 2001; Baldessarini et al., 2006; Cipriani et al., 2005; Müller-Oerlinghausen et al., 1992). Understanding how the above clinical factors moderate and mediate the effect of depression on the development of suicidal ideation is of clinical importance and can assist in identifying individuals at elevated risk for suicide and target interventions towards reducing this risk. The current study includes a group of individuals with bipolar dis-order types I and II, enrolled in a comparative effectiveness treatment trial of lithium vs. quetiapine plus adjunctive personalized therapy (Nierenberg et al., 2014). We examined the relationship between se-verity of depression and SI measured concurrently, over the 24-week period of the study. The MINI was also used to assess current and lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders and substance use dis-orders). Exclusion criteria were limited to maximize generalizability, but included a history of nonresponse or intolerable side effects with lithium or quetiapine, and active substance dependence within the past 30 days (a history of substance abuse was not an exclusion criteria). The Institutional Review Boards of the 11 study sites approved the study protocol. All participants provided written informed consent. Mood symptom severity and suicidality were assessed with the Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale (BISS) at baseline and all sub-sequent scheduled study visits (weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24-end of study) (Bowden et al., 2007; Gonzalez et al., 2008). The BISS is a 45-item clinician rated questionnaire with subscales for depression, mania, irritability, anxiety, and psychosis. The BISS questionnaire, item 4 asks about suicidal tendencies, including preoccupation with thoughts of death or suicide. This score was used in our analysis as a marker of severity of suicidal ideation. In our calculation of BISS-depression score, the suicidality item was not included to avoid redundancy. The suicide severity score is from 0 (none at all) and 1 (Slight; e. g. Occasional thoughts of death (without suicidal thoughts), “I would be better off dead” or “I wish I were dead” with 4 (Severe: e.g. often thinks of suicide and has thought of a specific plan or has made a suicidal gesture or attempt) being the highest score. This is different from the PHQ-9 questionnaire that has a single question, “Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” and four options for severity (Not at all, Several days, More than half the days, and Nearly every day). According to the PHQ-9 the individual can have no actual suicidal intention and score higher than an individual who has actual suicidal ideation, just not every day. In the BISS, higher scores indicate more severe suicidal ideation. Our study had two goals. First, we wanted to understand the dif-ferences between patients with bipolar disorder who did and who did not experience SI while depressed. Second, we wanted to understand how the relationship between depression and SI changed during the course of the comparative effectiveness trial. In our first analysis, we examined whether baseline clinical vari-ables including age, gender, age of illness onset, bipolar subtype (I vs. II), lifetime comorbid anxiety or substance use disorders, prior suicide attempts, history of childhood abuse and assignment to treatment with lithium vs. quetiapine affected the direction or strength of the re-lationship between depression severity and suicidal ideation during the course of the study (a moderator effect (Baron, 1986)). Although prior research has identified most of the above named variables as predictors of suicide risk, our moderator analysis examined the significance of these effects when both the direct effect of depressed mood and the interaction of depression and the moderator on SI are taken into con-sideration. In the second analysis, a mediator analysis (Baron, 1986), we ex-plored if symptoms of mania and irritability (which are associated with mixed episodes), anxiety and measures of quality of life and impairment in functioning (all of which have been found to be associated with SI), when collected at the same time as measures of depression severity and SI, could account for some of the relationship between depression and SI. Although we did not expect full mediation (i.e. the relationship between depression and suicide being completely explained by one of our mediator variables), we predicted that for some individuals, these We were not able to identify previous research that has examined the BISS suicide question as we have. However, multiple other studies have used item 9 from the PHQ-9 as a measure for suicide risk. (Bauer et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2016, 2013). The use of the PHQ-9 item 9 has been criticized (Na et al., 2018) with the PHQ-9 generating more false positive rates than the C-SSRS (Viguera et al., 2015). There are also 165 Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 M. Kamali, et al. concerns about using a single item from a questionnaire. This is a limitation of our analysis and any interpretation of our results should take this limitation into consideration. Functional impairment was measured with the LIFE-Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT), a semi-structured interview that measures impairment in four domains: work, interpersonal re-lationships, satisfaction and recreation (Leon et al., 2000). Scores of individual subscales range from 1–5, with higher scores indicating more impairment. Life satisfaction was assessed with the self-reported Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) (Endicott et al., 1993). This questionnaire measures level of satisfaction in ten areas (physical health, subjective feelings of wellbeing, work, household duties, school/course work, leisure time activities, social relationships, general activities, satisfaction with medications and overall life satisfaction). Higher scores indicate more satisfaction in that area. The Data for these questionnaires were collected at baseline, and weeks 12 and 24. 0.001). After adding each moderator to the model the coefficient for depression remained significant (0.022 – 0.031, all p values < 0.001); moderators with a significant interaction with depression were bipolar type (−0.005, p = 0.03) and history of suicide attempts (0.008, p = 0.002). To examine the mediator effects of our variables of interest, we evaluated several other associations represented in Fig. 1. Depression was significantly associated with each of the potential mediators (a 1 in Table 3, also Fig. 1model 1) and each of the potential mediators was significantly associated with suicidal ideation (b1 in Table 3, also Fig. 1-model 2). The direct and mediated effect of depression scores, illu-strated in Fig. 1- models 3 and 4, are given in Table 4 (c1 and g1). In a full mediation relationship, g1 would be zero. This would indicate that all the effect of depression on suicidal ideation was through the med-iator of interest; however, we did not expect full mediation. Rather we predicted that the magnitude of c1 would be reduced when the med-iator was present in the model. Although we cannot calculate α, the coefficient a1 is an approximation and was highly significant for all variables (Table 3). Given these criteria, this analysis showed that BISS-anxiety score, LIFE-RIFT total and satisfaction sub-scores, and the Q-LES-Q subscales, other than Physical, School and Medications, were significant mediators of the effect of depression on suicidal ideation. Although the relative coefficient changes ( %) for Satisfaction with Medications and School/Course work were significant, these variables were not significantly associated with SI in the model (as shown by g2) and as such cannot be considered mediators. Mania or irritability scores were not significant mediators. 2.1. Statistical analyses Analyses were conducted using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with repeated measures utilizing SAS 9.3 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., 2011). We analyzed the BISS item score as a con-tinuous variable (even though it is an ordinal variable), without any assumptions of normal distribution and used a GEE model with an identity link (using the robust standard errors for p-values, CIs). To calculate the moderating effects of the variables of interest, we fit linear GEE models using suicidality scores as the dependent variable and depression severity score, each of the possible moderators, and the depression-by-moderator interaction term as independent variables. If the interaction term is significant, it indicates that the additional variable does, indeed, increase or decrease (moderate) the association between suicidality and depression. To determine whether concurrent symptoms or stressors account for (mediate) some or all of the observed effect of depression on suicidality, we fit the linear GEE models re-presented in Fig. 1. To assess mediation, we computed the percent change that occurred in the depression coefficient when introducing the mediator into the model (i.e. change between c1 and g1 in models 3 and 4 in Fig. 1). We computed the 4. Discussion Our study has several important and clinically significant findings. Lithium or quetiapine did not have different moderating effects on suicidal ideation. Prior research has suggested that lithium reduces completed and attempted suicide. These include several meta-analyses of lithium studies (Baldessarini et al., 2006; Cipriani et al., 2005), which include studies with both bipolar and major depressive disorder participants. Some compare lithium to placebo or an anti-depressant or mood stabilizing agent and the outcomes of interest were completed or attempted suicide. By contrast, our study was limited to 24 weeks, fo-cused on suicidal ideation and included only bipolar participants who were not selected based on high suicide risk. It also included an active comparator with proven effectiveness in bipolar disorder, and allowed for adjunctive therapies. It is possible and has been suggested that li-thium's anti-suicidal properties are due to effects on impulsive and aggressive behavior (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al., 1992) and as such it should affect attempts more than ideation. An alternative explanation for the discrepancy in our finding is that the effects on suicide are primarily through better control of mood, and effective reduction in depression severity is the main reason for reduction in suicidal risk. In our sample with two effective treatment options, no difference in SI was detected. relative change in coefficient c1 as (g1-c1)/c1 and computed its significance using a bootstrap method. A two-tailed significance threshold of P < 0.05 was used with no correction for multiple comparisons. For this analysis, we chose a cross sectional model of mediation rather than a time lagged analysis. Cross sectional examination of mediation can generate significantly biased estimates of longitudinal mediation parameters (Maxwell and Cole, 2007). However with time lag designs, estimates of effects in longitudinal models can change greatly depending on the chosen time interval (Cole and Maxwell, 2003). The appropriate time lag to measure a change in de-pression leading to a change in the variable of interest and then SI is not known. We have thus chosen concurrent measurements of depression, the mediators, and SI given the close temporal relationship between mood and anxiety symptoms, quality of life and impairment measures and SI. However, this is a limitation in our study and the chosen ana-lysis model and our findings should be interpreted with caution given this limitation. Among the other moderators examined, only bipolar type and past suicide attempts were significant. Age, gender, age of illness onset, comorbid anxiety, comorbid substance use and childhood abuse were neither individually predictive of suicide when depression severity was included in the model, nor did they moderate the effects of depression. This emphasizes the importance of depression severity in the develop-ment of suicidal ideation in patients with bipolar disorder (Umamaheswari et al., 2014). Past suicide attempt did not independently predict current suicidal ideation above and beyond the effects of depression. However, a history of suicide moderated the effect of depression on suicidal ideation, meaning those with past suicide attempts were prone to having higher SI with similar levels of depres-sion compared to those without past suicide attempts. We also found that bipolar I and II individuals show different levels of SI depending on the severity of depression. The interaction effect for bipolar type 3. Results 482 participants with bipolar I or II were randomized to either li-thium with APT or quetiapine with APT. The mean (SD) on the BISS suicidality item for the lithium and quetiapine groups were 0.7 (0.98) and 0.7 (1.02) respectively. The mean (SD) number of visits per parti-cipant was 7.51 (2.38). Demographics of participants are summarized in Table 1. The results of the moderator analysis are summarized in Table 2. The unmoderated coefficient for depression on SI was 0.023 (p < 166 M. Kamali, et al. Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 Fig. 1. Description of models in the mediator analysis. D=Depression, M=Mediator, SI=Suicidal Ideation. indicates that with less severe depression (BISS depression scores less than 25), individuals with bipolar II have more severe suicidal ideation (compared to bipolar I individuals) while if the scores of BISS depres-sion increase over 25, individuals with bipolar I report more severe suicidal ideation. Some studies comparing suicidal risk in bipolar I and II have not shown significant differences in suicide attempts or risk between the two groups (Novick et al., 2010; Valtonen et al., 2005), while others show increased risk with bipolar I (Bobo et al., 2018). Our findings are suggestive that bipolar I and II individuals may have dif-ferent risks for developing SI. This variability in risk may be due to difference in comorbidities, severity of illness or study population, but our study is not fully able to explain the reason for this observation. Further research into the differences in suicide risk between bipolar I and II are warranted. 2001). Our study not only shows that life satisfaction affects SI, but also suggests that some of the effect of depression on SI is mediated through life satisfaction. Depression leads to lower life satisfaction, which itself leads to more SI. Co-occurring mania, irritability and anxiety symptoms showed ef-fects that were in contrast to our initial predictions. Mania and irrit-ability, which are prominent features of mixed states were not in-dependently predictive of SI, even though in bivariate models, they were strongly predictive of SI (Table 3). Similar to reports by Fiedorowicz et al. (2019) in our sample the higher levels of SI seen in mixed states are better explained by the presence of more severe de-pression in these individuals. In bivariate models, anxiety had a positive correlation with SI (Table 3) but in the mediated model, the direction of the association reversed and anxiety had a negative correlation with SI and the mediated coefficient for depression actually increased (from 0.0236 to 0.0374, a statistically significant change; p = 0.00136). This may indicate that the mediating relationship is in the opposite direc-tion, with depression mediating the effect of anxiety on SI (Thompson et al., 2005). In the STEP-BD study, although anxiety was found to be closely related to SI, the relationship was no longer sig-nificant when adjusted for current recovery status (Simon et al., 2007). Similar findings were reported in the Jorvi Bipolar Study (Valtonen et al., 2005) where depression and hopelessness were the strongest predictors of SI in multivariate models, even though multiple other variables such as anxiety were predictive in bivariate analyses. In our study population, depression and anxiety scores were highly cor-related (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.52, p < 0.0001), and it may be impossible to separate the effects of the two so this finding should be interpreted with caution. Satisfaction with life emerges as an important mediator of the effect of depression on suicidal ideation. Among the sub-scores of the LIFE-RIFT, only life satisfaction is a statistically significant mediator. The total score is also significant, but it appears that the main effect is through the Satisfaction sub-score. Impairment in work (which includes impairment in employment, school or household duties), impairment in relationships (which includes relationship with spouse, children, other relations and friends) or ability to enjoy recreational activities do not show an independent effect on SI above and beyond the effects of de-pression. On the other hand, the life satisfaction sub-score on the LIFE-RIFT and most subscales on the Q-LES-Q which measure satisfaction and the ability to enjoy different areas of daily life show a mediating effect on SI. The non-significant scores on the Q-LES-Q include the Physical Health, School and Medication Satisfaction sub-scores. Other studies have shown that lower life satisfaction is associated with higher rates of depression (Heli Koivumaa-Honkanen MD et al., 2004), suicidal ideation (Heisel and Flett, 2004), suicide attempts (Claassen et al., 2007; Ponizovsky et al., 2003; Valois et al., 2004) and completed suicide (Fujino et al., 2005; Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., 5. Limitations Our study has several limitations. The study was limited to bipolar I 167 0.8 −−0.0005[0.006,0.005] 0.1 −0.[0.001,0.009]003 0020. 0.[0.003,0.01]008 −0030.[0.002,0.009] 0.1 −0.[0.001,0.004]001 30. 30. 0.9 030. 50. 0.1 0.1 0.5 −020.[0.06, 0.1] − −0.07[0.1, 0.03] − −0.06[0.1, 0.02] −0.[0.04,0.06]03 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 P value <0.001 <0.001 − −0.003[0.007, 0.000] −0080.[0.08, 0.1] a Moderator as predictor of SI P value 168 ffiCoecient [95% CI]. a Interaction between moderatorand b depression as predictor of SI. .02 [.02, 0.03] 241 (50.2%) 257 (53.3%)Lithium240(49.8%) Quetiapine Yes Treatmentgroup .02 [.02, 0.02] 173 (36.1%)No224(46.5%) Yes PastHistoryofChildhoodAbuse .02 [.02, 0.02] 300 (62.2%)No306(63.9%) Yes PastHistoryofSuicideAttempt .02 [.01, 0.02] 277 (57.4%)No182(37.8%) Yes Lif e ti m e Co m o r b id S u b s tan ce U s e D is o r d er .02 [.02, 0.02] 205 (42.5%) Type IINo Lif etimeComor bidAnxietyDisorder .02 [.01, 0.03] .03 [.02, 0.03] 283 (58.7%)15.(±7.78)68 329 (68.2%) Female I BipolarType Type Ageofillnessonset .02 [.01, 0.03] .02 [.02, 0.03] Table2ff Mo d er ator s of th eeecto f d epr es s ion o n suicidal ideation. and II patients treated in an outpatient setting and as such, our fi ndings cannot be generalized to other diagnoses or other treatment settings. Our sample was not selected as a high suicide risk sample, and the measure of suicidal ideation was a single item from the BISS. The BISS suicide question has not been previously validated for use as a single item and we were unable to find another study that has used this item the way we have. Also, our follow up period was 24 weeks and any differences in anti-suicidal effects of lithium and quetiapine may not be noticeable in this time frame. Although our sample size was relatively large, it may not have been large enough to detect smaller effects and the negative findings may not represent a true lack of significance. However, findings with small effects may not have much clinical significance. Our findings related to anxiety are of interest and in conflict with our initial hypothesis. Due to the high correlation between de-pression and anxiety scores in our sample, our ability to examine the effects of each variable independently is limited. Our mediation ana-lysis was done on cross sectional data, which can generate significantly biased estimates of longitudinal mediation parameters. We chose a cross sectional model given the high variability of suicidal ideation reported in previous research (Kleiman et al., 2017). We recognize that our model for analysis is not the only possible explanation for the convergence of symptoms that occur in bipolar patients. Without un-derstanding the biology of these conditions, any assumptions of caus-ality in our mediation model are speculative. Our mediation models make assumptions regarding causality and directionality that are based on strong cross sectional correlations between symptoms. An alter-native explanation for this convergence of symptoms is that all variables are caused by a common factor, which is not included in this model. Our analysis did not find evidence of mediation in our data, other than for life satisfaction. Interpretation of our finding should Age 8838. ( ± 12.1) Gender Male 199 (41.3%) Abbreviations: BISS (Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale), LIFE-RIFT (Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range Impaired Functioning Tool), Q-LES-Q (Qualityof-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire). Depression as predictor of SI a 476 481 481 476 481 Variabl e N (%), Or Mean ( ± SD) 14.2 ± 3.3 3.4 ± 0.9 3.4 ± 1.1 3.6 ± 1.3 3.7 ± 1.2 0.1 239 449 67 478 475 478 474 475 − −0.03[0.07, 0.01] ± 21.5 ± 21.9 ± 22.9 ± 22.0 ± 19.0 ± 17.7 ± 40.4 ± 24.5 52.1 47.8 45.3 46.0 44.6 44.2 84.0 41.5 482 482 482 482 482 482 <0.001 479 478 −−−0.005[0.0.000]01, 41.5 ± 18.6 45.6 ± 17.8 Age Age of First Episode BISS Depression BISS Mania BISS Anxiety BISS Irritability Q-LES-Q Physical Health Subjective Feelings of WellBeing Work Household Duties School/Course Work Leisure Time Activities Social Relationships General Activities Satisfaction with meds Overall Life Satisfaction LIFE-RIFT Total Satisfaction Recreation Work Relationships −−0.0000[0.000,0.000] 479 482 0.2 0030. 173 (36.1%) 257 (53.3%) M±SD 38.8 ± 12.1 15.6 ± 7.7 17.5 ± 7.3 9.1 ± 6.3 15.9 ± 8.5 16.7 ± 8.5 − −0.003[0.009, 0.003] 0. [0.04, 0.2]1 482 482 482 482 <0.001 <0.001 283 (58.7%) 329 (68.2%) 277 (57.4%) 300 (62.2%) −−0.002[0.008,0.003] Female Gender Bipolar Type I Lifetime Comorbid Anxiety Disorder Lifetime Comorbid Substance Use Disorder Past History of Suicide Attempt Past History of Childhood Abuse −00010.[0.000,0.000] Total Observations in Category 050. 80. N (%) a , b Variable ffModeratingeect P value Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants. 20. Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 M. Kamali, et al. M. Kamali, et al. Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 Table 3 Associations between potential mediators, suicidal ideation and depression. Variable BISS Mania Anxiety Irritability LIFE-RIFT Total Satisfaction Recreation Work Relationships Q-LES-Q Physical Health Subjective Feelings of Well-Being work Household Duties School/Course Work Leisure Time Activities Social Relationships General Activities Satisfaction with meds Overall Life Satisfaction Direct association of mediators with depression (a1) Association of mediators with suicidal ideation, independent of depression status (b1) Coefficient Standard error P value Coefficient Standard error P value 0.06 0.42 0.34 0.007 0.007 0.010 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.003 0.002 0.002 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.17 0.04 0.05 0.04 0.03 0.005 0.001 0.002 0.002 0.002 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.07 0.29 0.15 0.14 0.10 0.006 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 −0.76 −0.84 −0.71 −0.63 −0.87 −0.82 −0.86 −0.88 −0.53 −1.13 0.03 0.02 0.05 0.04 0.10 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.07 0.04 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 −0.01 −0.01 −0.009 −0.009 −0.005 −0.01 −0.01 −0.01 −0.002 −0.01 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.002 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.0009 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.01 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.009 <0.001 Abbreviations: BISS (Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale), LIFE-RIFT (Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range Impaired Functioning Tool), Q-LES-Q (Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire). Table 4 Mediators of the effect of depression on suicidal ideation. Variable BISS Mania Anxiety Irritability LIFE-RIFT Total Satisfaction Recreation Work Relationships Q-LES-Q Physical Health Subjective Feelings of Well-Being work Household Duties School/Course Work Leisure Time Activities Social Relationships General Activities Satisfaction with meds Overall Life Satisfaction c1 P value g1 P value g2 P value % 0.02 0.02 0.02 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.02 0.02 0.02 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.002 −0.008 0.002 0.5 0.002 0.1 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.02 0.14 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.002 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0 −0.007 −0.004 −0.003 −0.001 −0.004 −0.003 −0.007 −0.0008 −0.006 95% Confidence Interval P value −0.8 16.1 −04.2 [−2.0, 0.3] [10.7, 21.4] [−7.4, −1.0] 0.2 0.001 0.09 0.01 <0.001 0.5 0.1 0.6 −17.3 −29.6 −3.8 −5.5 −2.1 [−25.2, −9.5] [−36.4, −22.8] [−9.1, 1.5] [−9.6, −1.4] [−5.5, 1.3] 0.01 <0.001 0.2 0.08 0.2 0.9 <0.001 0.01 0.003 0.6 0.005 0.007 <0.001 0.3 <0.001 −1.6 −30.0 −38.1 −11.4 −74.8 −21.0 −16.5 −30.9 −3.8 −30.9 [−6.9, 3.5] [−36.9, −23.2] [−48.0, −28.2] [−15.9, −6.9] [−96.3, −53.2] [−25.8, −16.2] [−22.3, −10.7] [−38.4, −23.3] [−5.4, −2.1] [−38.5, −23.3] 0.3 <0.001 <0.001 0.005 <0.001 <0.001 0.002 <0.001 0.009 <0.001 Abbreviations: BISS (Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale), LIFE-RIFT (Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range Impaired Functioning Tool), Q-LES-Q (Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire). c1: Unmediated coefficient for depression estimating suicidal ideation. g1: Mediated coefficient for depression estimating suicidal ideation. g2: Coefficient for mediator estimating suicidal ideation. %: Percent change in depression coefficient with addition of mediator to the model. consider these limitations. In our study, we chose to analyze the BISS item score as a con-tinuous variable (even though it is an ordinal variable) and used a GEE model with an identity link (using the robust standard errors for p-values, CIs). GEEs are semi-parametric and do not make distributional assumptions on the outcome (only a parametric form for the mean of the outcome), so we do not assume the outcomes are normally dis-tributed. There has been criticism regarding the use of parametric tests on Likert scales (Jamieson, 2004). Treating an ordinal variable as a continuous variable could lead to predicted values outside the range of the actual ordinal score and imposes the assumption that each sub-sequent category is equally distant numerically. For example, the average severity of SI in this sample was 0.7, which is not a valid score on the BISS. However, parametric tests are very robust with respect to violations of assumptions and can be used with Likert scales (Norman, 2010; Sullivan and Artino, 2013) and though we may not be able to interpret the means, the statistical inference we make on the coeffi-cients (the betas), is still valid. Also our choice of moderators and mediators is clearly not ex-haustive. For example we did not examine the effects of rapid cycling or 169 Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 M. Kamali, et al. sleep. Previous research has shown that sleep disturbances are asso-ciated with high-lethality suicide attempts across a diverse group of psychiatric patients (Pompili et al., 2013). systematic review of randomized trials. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1805–1819. Claassen, C.A., Trivedi, M.H., Rush, A.J., Husain, M.M., Zisook, S., Young, E., Leuchter, A., Wisniewski, S.R., Balasubramani, G., Alpert, J., 2007. Clinical differences among depressed patients with and without a history of suicide attempts: findings from the STAR*D trial. J. Affect. Disord. 97, 77–84. Cole, D.A., Maxwell, S.E., 2003. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. Coryell, W., Andreasen, N.C., Endicott, J., Keller, M., 1987. The significance of past mania or hypomania in the course and outcome of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 144, 309– 315. de Abreu, L.N., Nery, F.G., Harkavy-Friedman, J.M., de Almeida, K.M., Gomes, B.C., Oquendo, M.A., Lafer, B., 2012. Suicide attempts are associated with worse quality of life in patients with bipolar disorder type I. Compr. Psychiatry 53, 125–129. Endicott, J., Nee, J., Harrison, W., Blumenthal, R., 1993. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 29, 321–326. Fiedorowicz, J.G., Persons, J.E., Assari, S., Ostacher, M.J., Zandi, P., Wang, P.W., Thase, M.E., Frye, M.A., Coryell, W., 2019. Depressive symptoms carry an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in bipolar disorder without any additional contribu-tion of mixed symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12. 057. Author statement Contributors: Drs. Kamali, Reilly-Harrington, McInnis, McElroy, Ketter, Shelton, Deckersbach, Tohen, Kocsis, Calabrese, Gao, Thase, Bowden, Kinrys, Bobo, Brody, Sylvia and Nierenberg were investigators in the CHOICE study and recruited, assessed and treated the original sample. Dr. Kamali suggested this analysis and wrote the final version of the manuscript. Mr. Rabideau completed the statistical analysis. Ms. Chang assisted in literature search and writing the manuscript. All Authors have approved the final article. Role of the funding source Fujino, Y., Mizoue, T., Tokui, N., Yoshimura, T., 2005. Prospective cohort study of stress, life satisfaction, self‐rated health, insomnia, and suicide death in Japan. Suic. Life-Threat. Behav. 35, 227–237. Garno, J.L., Goldberg, J.F., Ramirez, P.M., Ritzler, B.A., 2005. Impact of childhood abuse on the clinical course of bipolar disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 186, 121–125. Goldberg, J.F., Allen, M.H., Miklowitz, D.A., Bowden, C.L., Endick, C.J., Chessick, C.A., Wisniewski, S.R., Miyahara, S., Sagduyu, K., Thase, M.E., Calabrese, J.R., Sachs, G.S., 2005. Suicidal ideation and pharmacotherapy among step-BD patients. Psychiatr. Serv. 56, 1534–1540. Gonzalez, J.M., Bowden, C.L., Katz, M.M., Thompson, P., Singh, V., Prihoda, T.J., Dahl, M., 2008. Development of the bipolar inventory of symptoms scale: concurrent va-lidity, discriminant validity and retest reliability. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 17, 198–209. The funding agency had no role in this study design; in the collec-tion, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; and in the decision to submit this article for publication. Acknowledgements The authors thank all the participants that volunteered for this clinical trial. Conclusion Heisel, M.J., Flett, G.L., 2004. Purpose in life, satisfaction with life, and suicide ideation in a clinical sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 127–135. Heli Koivumaa-Honkanen MD, M., Kaprio, J., Honkanen, R., Viinamäki, H., Koskenvuo, M., 2004. Life satisfaction and depression in a 15-year follow-up of healthy adults. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 39, 994–999. Jamieson, S., 2004. Likert scales: how to (ab)use them. Med. Educ. 38, 1217–1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02012.x. Kleiman, E.M., Turner, B.J., Fedor, S., Beale, E.E., Huffman, J.C., Nock, M.K., 2017. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. https://doi. org/10.1037/abn0000273. Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Honkanen, R., Viinamaeki, H., Heikkilae, K., Kaprio, J., Koskenvuo, M., 2001. Life satisfaction and suicide: a 20-year follow-up study. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 433–439. Leon, A.C., Solomon, D.A., Mueller, T.I., Endicott, J., Posternak, M., Judd, L.L., Schettler, P.J., Akiskal, H.S., Keller, M.B., 2000. A brief assessment of psychosocial functioning of subjects with bipolar I disorder: the life-rift. Longitudinal interval follow-up eva-luationrange impaired functioning tool. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 188, 805–812. López, P., Mosquera, F., de Leon, J., Gutiérrez, M., Ezcurra, J., Ramírez, F., Gonzalez-Pinto, A., 2001. Suicide attempts in bipolar patients. J. Clinic. Psychiatry 62, 963–966. Our study suggests that reported life satisfaction, even more than functional impairment, is a mediator of the effect of depression on SI. This has clinical significance, as elements of cognitive therapy that address cognitive distortions related to life satisfaction may be potential targets to reduce risk of suicide. Bipolar type and past suicide attempts also moderate the effects of depression, while most other variables lose significance when the effects of depression are considered. The most significant predictor of suicidal ideation in patients with bipolar dis-order remains the severity of depression. This further emphasizes the importance of treating depressive episodes to reduce suicide risk in bipolar disorder. References Ahrens, B., Müller-Oerlinghausen, B., 2001. Does lithium exert an independent antisuicidal effect? Pharmacopsychiatry 4, 132–136. Balázs, J., Benazzi, F., Rihmer, Z., Rihmer, A., Akiskal, K.K., Akiskal, H.S., 2006. The close link between suicide attempts and mixed (bipolar) depression: implications for sui-cide prevention. J. Affect. Disord. 91, 133–138. Baldassano, C.F., 2005. Illness course, comorbidity, gender, and suicidality in patients with bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 8–11. Baldessarini, R.J., Tondo, L., Davis, P., Pompili, M., Goodwin, F.K., Hennen, J., 2006. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long‐term lithium treatment: a meta‐analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 8, 625–639. Baron, R.M., 1986. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. American Psychological Association (PsycARTICLES), Washington, pp. 1173. Bauer, A.M., Chan, Y.-.F., Huang, H., Vannoy, S., Unützer, J., 2013. Characteristics, management, and depression outcomes of primary care patients who endorse thoughts of death or suicide on the PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28, 363–369. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2194-2. Bowden, C.L., Singh, V., Thompson, P., Gonzalez, J.M., Katz, M.M., Dahl, M., Prihoda, T.J., Chang, X., 2007. Development of the bipolar inventory of symptoms scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 116, 189–194. Bobo, W.V., Na, P.J., Geske, J.R., McElroy, S.L., Frye, M.A., Biernacka, J.M., 2018. The relative influence of individual risk factors for attempted suicide in patients with bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 225, 489–494. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.076. Chen, W.J., Chen, C.C., Ho, C.K., Chou, F.H., Lee, M.B., Lung, F., Lin, G.G., Teng, C.Y., Chung, Y.T., Wang, Y.C., Sun, F.C., 2011. The relationships between quality of life, psychiatric illness, and suicidal ideation in geriatric veterans living in a veterans' home: a structural equation modeling approach. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 19, 597–601. Maxwell, S.E., Cole, D.A., 2007. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. Müller-Oerlinghausen, B., Müser-Causemann, B., Volk, J., 1992. Suicides and para-suicides in a high-risk patient group on and off lithium long-term medication. J. Affect. Disord. 25, 261–269. Na, P.J., Yaramala, S.R., Kim, J.A., Kim, H., Goes, F.S., Zandi, P.P., Vande Voort, J.L., Sutor, B., Croarkin, P., Bobo, W.V., 2018. The PHQ-9 item 9 based screening for suicide risk: a validation study of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ)−9 item 9 with the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). J. Affect. Disord. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.045. Nierenberg, A.A., McElroy, S.L., Friedman, E.S., Ketter, T.A., Shelton, R.C., Deckersbach, T., McInnis, M.G., Bowden, C.L., Tohen, M., Kocsis, J.H., Calabrese, J.R., Kinrys, G., Bobo, W.V., Singh, V., Kamali, M., Kemp, D., Brody, B., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Sylvia, L.G., Shesler, L.W., Bernstein, E.E., Schoenfeld, D., Rabideau, D.J., Leon, A.C., Faraone, S., Thase, M.E., 2016. CHOICE (Clinical health outcomes initiative in comparative effectiveness): a pragmatic 6-month trial of lithium versus quetiapine for bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 90–99. Nierenberg, A.A., Sylvia, L.G., Leon, A.C., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Shesler, L.W., McElroy, S.L., Friedman, E.S., Thase, M.E., Shelton, R.C., Bowden, C.L., Tohen, M., Singh, V., Deckersbach, T., Ketter, T.A., Kocsis, J.H., McInnis, M.G., Schoenfeld, D., Bobo, W.V., Calabrese, J.R., the Bipolar, C.S.G., 2014. Clinical and health outcomes initiative in comparative effectiveness for bipolar disorder (Bipolar CHOICE): a pragmatic trial of complex treatment for a complex disorder. Clinic. Trials 11, 114–127. Norman, G., 2010. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the ``laws’’ of statistics. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 15, 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y. Novick, D.M., Swartz, H.A., Frank, E., 2010. Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: a review and meta‐analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord. 12, 1–9. Ösby, U., Brandt, L., Correia, N., Ekbom, A., Sparén, P., 2001. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 844–850. Pompili, M., Innamorati, M., Forte, A., Longo, L., Mazzetta, C., Erbuto, D., Ricci, F., Palermo, M., Stefani, H., Seretti, M.E., Lamis, D.A., Perna, G., Serafini, G., Amore, M., Cipriani, A., Pretty, H., Hawton, K., Geddes, J.R., 2005. Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a 170 Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 M. Kamali, et al. during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Bracket, personal fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., personal fees from MedAvante, personal fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America, grants and personal fees from Myriad, grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, grants and personal fees from Shire, grants and personal fees from Sunovion, grants from Allergan, grants from Brainsway, grants from Marriott Foundation, outside the submitted work. Girardi, P., 2013. Insomnia as a predictor of high-lethality suicide attempts. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 67, 1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12211. Ponizovsky, A.M., Grinshpoon, A., Levav, I., Ritsner, M.S., 2003. Life satisfaction and suicidal attempts among persons with schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 44, 442–447. Sanchez-Moreno, J., Martinez-Aran, A., Tabarés-Seisdedos, R., Torrent, C., Vieta, E., AyusoMateos, J., 2009. Functioning and disability in bipolar disorder: an extensive review. Psychother. Psychosom. 78, 285–297. Sheehan, D.V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K.H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., Dunbar, G.C., 1998. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric in-terview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59 (Suppl 20), 22–33 quiz 34-57. Simon, G.E., Coleman, K.J., Rossom, R.C., Beck, A., Oliver, M., Johnson, E., Whiteside, U., Operskalski, B., Penfold, R.B., Shortreed, S.M., Rutter, C., 2016. Risk of suicide at-tempt and suicide death following completion of the patient health questionnaire depression module in community practice. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 221–227. https:// doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m09776. Simon, G.E., Rutter, C.M., Peterson, D., Oliver, M., Whiteside, U., Operskalski, B., Ludman, E.J., 2013. Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr. Serv. 64, 1195–1202. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. Simon, N.M., Zalta, A.K., Otto, M.W., Ostacher, M.J., Fischmann, D., Chow, C.W., Thompson, E.H., Stevens, J.C., Demopulos, C.M., Nierenberg, A.A., 2007. The asso-ciation of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 41, 255–264. Slama, F., Bellivier, F., Henry, C., Rousseva, A., Etain, B., Rouillon, F., Leboyer, M., 2004. Bipolar patients with suicidal behavior: toward the identification of a clinical sub-group. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65, 1035–1039. Spearing, M.K., Post, R.M., Leverich, G.S., Brandt, D., Nolen, W., 1997. Modification of the clinical global impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res. 73, 159–171. Sullivan, G.M., Artino, A.R., 2013. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 5, 541–542. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-5-4-18. Suppes, T., Dennehy, E.B., Hirschfeld, R.M., Altshuler, L.L., Bowden, C.L., Calabrese, J.R., Crismon, M.L., Ketter, T.A., Sachs, G.S., Swann, A.C., Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Bipolar, D., 2005. The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66, 870–886. Suppes, T., Leverich, G.S., Keck Jr, P.E., Nolen, W.A., Denicoff, K.D., Altshuler, L.L., McElroy, S.L., Rush, A.J., Kupka, R., Frye, M.A., 2001. The Stanley foundation bipolar treatment outcome network: II. demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. J. Affect. Disord. 67, 45–59. Thompson, E.A., Mazza, J.J., Herting, J.R., Randell, B.P., Eggert, L.L., 2005. The med-iating roles of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness on adolescent suicidal behaviors. Suic. LifeThreat. Behav. 35, 14–34. Tondo, L., Baldessarini, R.J., Hennen, J., Minnai, G.P., Salis, P., Scamonatti, L., Masia, M., Ghiani, C., Mannu, P., 1999. Suicide attempts in major affective disorder patients with comorbid substance use disorders. J. Clinic. Psychiatry 60 (Supplement 2), 63–69. Terence A. Ketter, MD has received grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Allergan Pharmaceuticals, personal fees and other from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Inc., personal fees from Navigen, personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Supernus Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Teva Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Merck & Co., Inc., personal fees from American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., outside the submitted work. Richard C. Shelton, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Allergan, grants from Assurex Health, grants from Avanir Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Cerecor, Inc, personal fees from Clintara LLC, grants from Genomind, grants and personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceutica, personal fees from Medtronic, Inc., grants from Novartis, Inc., personal fees from Pfizer, Inc., grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, grants from Alkermes, PLC, grants and personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, grants from NeuroRx Inc., outside the submitted work. Thilo Deckersbach, PhD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; grants from National Institutes of Health, grants from Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, grants from Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, grants from Depression and Bipolar Alternative Treatment Foundation, grants and personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc, personal fees from MGH Psychiatry Acadamy, personal fees from BrainCells, Inc, personal fees from Clintara, Inc., personal fees from Systems Research and Applications Corporation, per-sonal fees from Boston University, personal fees from Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, personal fees from National Association of Social Workers Massachusetts, personal fees from Massachusetts Medical Society, grants and personal fees from Tufts University, personal fees from National Institute on Drug Abuse, grants and personal fees from National Institute of Mental Health, grants from International OCD Foundation, grants from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Cogito, Inc., personal fees from Oxford University Press, grants from Brain and Behavior Foundation, grants from Tourette Syndrome Association, grants from National Institute on Aging, grants from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, grants from The Forest Research Institute, grants from Shire Development, Inc., grants from Medtronic, grants from Cyberonics, grants from Northstar, grants from Takeda, outside the submitted work. Mauricio Tohen, MD DrPH. MBA reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from straZeneca, Abbott, BMS, Lilly, GSK, J&J, Otsuka, Roche, Lundbeck, Elan, Allergan, Alkermes, Merck, Minerva, Neuroscience, Pamlab, Alexza, Forest, Teva, Sunovion, Gedeon Richter, and Wyeth, outside the submitted work. Tondo, L., Isacsson, G., Baldessarini, R.J., 2003. Suicidal behaviour in bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs 17, 491–511. Tondo, L., Lepri, B., Baldessarini, R., 2007. Suicidal risks among 2826 Sardinian major affective disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 116, 419–428. Umamaheswari, V., Avasthi, A., Grover, S., 2014. Risk factors for suicidal ideations in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 16, 642–651. Valois, R.F., Zullig, K.J., Huebner, E.S., Drane, J.W., 2004. Life satisfaction and suicide among high school adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 66, 81–105. Valtonen, H., Suominen, K., Mantere, O., Leppamaki, S., Arvilommi, P., Isometsa, E.T., 2005. Suicidal ideation and attempts in bipolar I and II disorders. J. Clinic. Psychiatry 66, 1456– 1462. Viguera, A.C., Milano, N., Laurel, R., Thompson, N.R., Griffith, S.D., Baldessarini, R.J., Katzan, I.L., 2015. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with the pa-tient health questionnaire item 9 and the Columbia suicide severity rating scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2015. 04.005. James H. Kocsis, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study. Joseph R. Calabrese, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study. Keming Gao, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Sunovion, personal fees from Otsuka, grants from Cleveland Foundation, grants from Brian and Behavior Research Foundation, outside the submitted work. Michael E. Thase, MD reports grants and personal fees from Alkermes, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly & Co, grants and personal fees from Forest Laboratories, personal fees from Gerson Lehman Group, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Guidepoint Global, personal fees from H. Lundbeck A/S, personal fees from MedAvante, personal fees from Merck and Co., personal fees from Neuronetics, Inc., personal fees from Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Otsuka, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Shire US, Inc., personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., personal fees from Takeda, other from American Psychiatric Foundation, other from Guilford Publications, other from Herald House, other from W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., other from Peloton Advantage, personal fees from Cerecor, Inc., personal fees from Moksha8, personal fees from Pamlab L.L.C. (Nestle), personal fees from Allergan, personal fees from Trius Therapeutical, Inc., personal fees from Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, grants from AssureRx, grants from Avanir, grants from Forest Pharmaceuticals, grants from Janssen, grants from Intracellular, grants from National Institutes of Health, grants from Takeda, outside the submitted work. Masoud Kamali, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; grants from Janssen Pharmaceutica, grants from Assurex Health, outside the submitted work. Noreen A. Reilly-Harrington, PhD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; other from Oxford University Press, other from American Psychological Association, other from New Harbinger, other from United Biosource/Clintara, outside the submitted work. Weilynn C. Chang, BS has nothing to disclose. Melvin McInnis, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Otsuka Pharmacueticals, personal fees from Takeda Pharmacueticals, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. McInnis has a patent US patent 9685174 B2: Mood Monitoring of Bipolar Disorder using Speech Analysis issued. Charles L. Bowden, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study. Susan L. McElroy, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 171 Journal of Affective Disorders 259 (2019) 164–172 M. Kamali, et al. Dustin J. Rabideau, MS has nothing to disclose. Gustavo Kinrys, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study. Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Takeda/Lundbeck, grants and personal fees from AlfaSigma (formerly Pamlabs), grants from GlaxoSmithKlein, personal fees from Alkermes, grants from NeuroRx Pharma, personal fees from PAREXEL, personal fees from Sunovian, personal fees from Naurex, personal fees from Hoffman La Roche/Genentech, personal fees from Eli Lilly & Company, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from SLACK Publishing, personal fees from Physician's Postgraduate Press, Inc., grants from Marriott Foundation, grants from National Institute of Health, grants from Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, grants from Janssen, grants from Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, grants from Intracellular Therapies, other from Appliance Computing, Inc., other from Brain Cells, Inc., personal fees from Shire, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. William V. Bobo, MD, MPH reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study. Benjamin Brody, MD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study, and grant from the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium outside the submitted work. Louisa G. Sylvia, PhD reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Concordant Rater Systems, personal fees from United Biosource Corporation, personal fees from Clintara, personal fees from Bracket, personal fees from Clinical Trials Network and Institute, personal fees from New Harbinger, outside the submitted work; and she has also received grant/research support from NIMH, PCORI, AFSP, and Takeda. 172