Enviado por

common.user3349

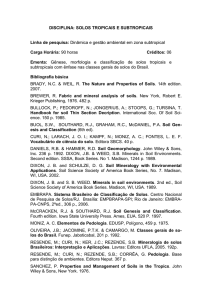

Revista 23 - artigo solo da amazonas