LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

ATUALIZAÇÃO / UPDATE

Luxação inveterada do ombro

Chronic unreduced shoulder dislocation

MARCO ANTONIO DE CASTRO VEADO1

RESUMO

ABSTRACT

O melhor tratamento para a luxação inveterada do

ombro é, na verdade, a prevenção. Por isso, devem ser sempre valorizados a história clínica e o exame físico. Atenção

redobrada deve ser dada aos pacientes epilépticos, alcoólatras, politraumatizados e àqueles em tratamento prolongado de “capsulite adesiva”. A incidência em axilar na

investigação radiológica é indispensável, pois ela é a chave

para o diagnóstico. Muitas vezes “o não fazer nada” constitui a melhor forma de tratamento dessa lesão. No planejamento operatório, identificar: o tamanho do defeito da

cabeça umeral, as perdas ósseas da glenóide, o estado do

manguito rotador, principalmente o do músculo subescapular, e as lesões nervosas. A tomografia computadorizada e a ressonância magnética são exames complementares de grande valia. Para o ato cirúrgico são indispensáveis:

material apropriado, auxiliares treinados e em número

suficiente. Redução aberta está bem indicada nos casos

mal definidos ou que datem mais de duas semanas do trauma. As cirurgias reconstrutoras são a indicação de eleição

nos pacientes mais jovens e com lesão da cabeça umeral

menor que 45% da superfície articular. As hemiartroplastias são a melhor escolha quando o defeito umeral está

acima desse percentual, e as artroplastias totais quando

há comprometimento da glenóide, sempre dependendo da

integridade do manguito rotador. É indicação questionável operar paciente desmotivado, pouco disposto a submeter-se ao programa de reabilitação funcional.

The best treatment for the chronic shoulder dislocation is

undeniably the prevention. Therefore, the clinical history

and physical examination must always be valued. Doubled

attention must be paid to epileptic patients, alcoholics, multiple injured patients, and those with a prolonged treatment

of “adhesive capsulitis”. The radiographic axillary view is

essential, as it is the key for the diagnosis. Many times the

“do not touch” is the best form of treatment for such injury.

During operative planning, the size of the humeral head

defect, glenoid bone losses, rotator cuff status, mainly the

subscapularis muscle, and nerve injuries must be identified.

Computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are complementary tests of great value. Appropriate

material, trained and numerically sufficient surgical personnel are essential for the surgical procedure. Open reduction is well indicated for ill-defined cases or those evolving

more than two weeks from the trauma. Reconstruction procedures are indicated for younger patients, and those with a

humeral head lesion corresponding to less than 45% of the

joint surface. Hemiarthroplasties are the best choice when

the humeral defect is above that percentage, and total arthroplasties suit better glenoid compromising, ever depending on the rotator cuff integrity. It is debatable whether to

operate an unmotivated patient, who would not be ready to

be submitted to a functional rehabilitation program.

Key words – Shoulder; hemiarthroplasty; rotator cuff

Unitermos – Ombro; hemiartroplastia; manguito rotador

1. Cirurgião de Ombro do Hospital Mater Dei e Hospital da Previdência-IPSEMG de Belo Horizonte/MG; Professor da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de

Minas Gerais-Hospital Universitário São José.

1. Shoulder Surgeon, Hospital Mater Dei and Hospital da Previdência –

IPSEMG, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Associate Professor, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais-Hospital Universitário São José,

Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Endereço para correspondência (Correspondence to): Av. Celso Porfírio Machado, 104 – 30320-400 – Belo Horizonte, MG. Tels.: (31) 3286-3156 (residência), 32615700 e 3261-5157 (consultório). E-mail: [email protected].

Copyright RBO2004

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

1

M.A. CASTRO VEADO

INTRODUÇÃO

INTRODUCTION

Segundo Loebenberg e Cuomo, foi White quem, pela primeira vez, em 1741, publicou comentários sobre o tratamento da luxação posterior crônica do ombro, chamando atenção

para a gravidade dessas lesões, mostrando seu resultado final

sombrio(1).

According to Loebenberg and Cuomo, White first published

in 1741 commentaries on the treatment of the chronic posterior shoulder dislocation, calling attention to the severity of

those injuries, with a reserved outcome(1).

Centuries have been through and this diagnosis is still being neglected. With the advances in the knowledge and treatment of shoulder diseases, unreduced chronic dislocation has

been sporadically found in orthopedic practice.

The diagnosis is eventually known, but the many patients –

mainly the poorest – do not have their problem solved due to

precarious conditions of our health system, the region where

they live, or the lack of somebody able to solve the problem.

Alcoholics, diabetics (seizures due to nocturnal hypoglycemia), and epileptic patients that use anticonvulsive medications erratically are often subject to have their dislocation

neglected, whereas the same happens with comatose victims

of serious accidents, with multiple injuries in the ICU, where

other higher-risk injuries demand the attention of the attending team(2,3).

Quite frequently the patient does not safely inform how long

has the shoulder been dislocated, posing a great risk, as attempts of closed reduction may fracture the humerus, already

atrophic by disuse, thus compelling the orthopedic surgeon to

carry out an eventually complex open reduction, without previous preoperative planning.

Time produces capsule, tendon and muscle scarring and

adhesions, making the reduction difficult, and eventually impossible. The humeral head cartilage softening, along with

intense soft tissue contracture and important glenoid bone

loss, are quite often times associated to fractures and nerve

injuries, predicting a poor outcome for those injuries(2).

When is a dislocation considered to be chronic?

In accordance to Schultz et al, a dislocation is considered

chronic after 24 hours of an unrecognized trauma(4). Others

consider after 45 days(5), although most – according to Rowe

and Zarins – stated a period above 21 days(6). We consider

that after the second week of trauma, we must be prepared for

an open reduction.

As to the direction of displacement, there is no agreement

either.

According to Schultz et al, and Rowe and Zarins, the posterior dislocation is more frequent than the anterior dislocation. Seizures account for 1/3 of posterior dislocations, and

half of anterior dislocations(4,6). Buhler and Gerber showed,

however, an equal frequency between both(7). Our experience

Séculos já se passaram e esse diagnóstico continua sendo

negligenciado. Com o avanço no conhecimento e no tratamento das afecções do ombro, a luxação crônica não reduzida tem sido encontrada na prática ortopédica de maneira esporádica.

Algumas vezes, o diagnóstico é conhecido, mas muitos pacientes, principalmente os mais humildes, não têm o problema resolvido devido às condições precárias do nosso sistema

de saúde, da região que habitam ou pela falta de alguém capaz de solucionar o problema.

Pacientes alcoólatras, diabéticos (convulsão por hipoglicemia noturna), epilépticos que fazem uso de medicamentos

anticonvulsivantes de maneira desordenada estão sujeitos com

freqüência a ter sua luxação negligenciada, o mesmo ocorrendo com vítimas de acidentes graves, em coma, com múltiplas lesões, internados em CTI, quando outras lesões de maior

risco e importância desviam a atenção da equipe de atendimento(2,3). Com muita freqüência, o paciente não informa com

segurança há quanto tempo o ombro está luxado, decorrendo

daí grande risco, pois as tentativas de redução incruenta podem fraturar o úmero já atrofiado por desuso, ou então obrigar o ortopedista a realizar uma redução aberta, às vezes complexa, sem prévio planejamento operatório.

O tempo faz com que as contraturas e aderências da cápsula, tendões e músculos dificultem a redução, tornando-a impossível após certo tempo. O amolecimento da cartilagem da

cabeça umeral deslocada, junto com intensa contratura de tecidos moles e perda óssea importante na glenóide, muitas vezes associada às fraturas e lesões nervosas, fazem com que

essas lesões tenham prognóstico reservado(2).

Quando uma luxação é considerada crônica?

Segundo Schultz et al, quando não são reconhecidas após

as 24 horas do trauma(4). Outros acham que seria após 45 dias(5),

embora a maioria, segundo Rowe e Zarins, estabeleça o prazo

como superior a 21 dias(6). A nossa opinião é de que após a

segunda semana do trauma já devemos estar preparados para

uma redução aberta.

Em relação à direção do deslocamento, também não existe

concordância.

2

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

in 12 cases of our sampling of

Na experiência de Schultz

unreduced dislocations showet al e Rowe e Zarins, o desed the same frequency as to the

locamento posterior é mais

incidence of anterior and posfreqüente que o anterior com

terior dislocations.

as crises convulsivas resIn a research performed in

pondendo por 1/3 das luxaNew England, USA, 33% of the

ções posteriores e metade das

surgeons with one to five years’

anteriores(4,6). Buhler e Gerexperience had dealt with at

ber mostraram, entretanto,

least one case of chronic

freqüência igual entre as

shoulder dislocation, whilst

duas(7). Nossa experiência

the incidence was of 90% for

em 12 casos de luxação irrethose with more than 20 years’

dutível mostra também igual

freqüência em relação à in- Fig. 1 – Radiografia do ombro em axilar mostrando uma luxação experience. Therefore, the experience with chronic glenocidência de luxação anterior posterior

Fig. 1 – Shoulder axillary view showing a posterior dislocation

humeral dislocation is directe posterior.

ly linked to the time length of

Em pesquisa realizada em

orthopedic practice(6).

New England, EUA, 33% dos

cirurgiões com um a cinco anos de experiência viram ou traIn 1855, according to Matsen and Rockwood, Malgaigne

taram pelo menos um caso de luxação crônica do ombro, enpublished on 37 cases of posterior dislocations, based solely

quanto a incidência foi de 90% naqueles com mais de 20 anos

on careful observation, about 40 years before the discovery

de experiência. Portanto, a experiência com a luxação escaof X-rays.

puloumeral crônica está diretamente relacionada com o temA careful clinical history, a thorough physical examinapo de prática do ortopedista(6).

tion, added to the essential axillary view, are the key for the

Em 1855, segundo Matsen e Rockwood, Malgaigne publicorrect identification of the injury that will take us straight to

cou 37 casos de luxação posterior, cerca de 40 anos antes da

the diagnosis(1,2,8,9) (figure 1).

descoberta do RX, unicamente baseado em sua atenta obserThere must be a high degree of suspicion about a blocked

vação(8).

dislocation, especially a posterior dislocation, whenever a

História clínica minuciosa, exame físico atento e detalhapatient presents with shoulder pain and range of motion limdo, aliados à investigação radiológica com a indispensável

itation that are resistant to treatment.

incidência em axilar, são a chave para a correta identificação

Once the diagnosis of unreduced chronic shoulder dislocada lesão e nos levarão certamente ao diagnóstico(1,2,8,9) (fig. 1).

tion is done, there are some questions to be asked. The most

Suspeitar sempre da luxação bloqueada, principalmente a

important, according to some authors, is to know if the paposterior, frente a qualquer paciente com dor e limitação de

tient is symptomatic(2,3,10).

It is not uncommon to find patients presenting old, painmovimentos do ombro resistentes ao tratamento.

free dislocations, with reasonable range of motion. ObviousUma vez diagnosticada a luxação crônica não reduzida do

ly, those patients will not be candidates for a surgical interombro, existem vários questionamentos a ser feitos. O mais

vention (figure 2).

importante, segundo alguns autores, é saber se o paciente é

Another aspect to consider is the rehabilitation. It is imsintomático(2,3,10).

Não é incomum encontrarmos pacientes com luxações anportant to previously identify if the patient has capability, motigas sem dor e com amplitude razoável de movimentos. Obtivation, and conditions to take the long and intense program

viamente, que esses não serão candidatos a uma intervenção

of physical therapy that follows the surgery; alcoholics, epicirúrgica (fig. 2).

leptics and people at the lowest social level are not usually

Outro aspecto diz respeito à reabilitação. É importante idencooperative.

tificar previamente se o paciente tem habilidade, motivação e

The type of surgical procedure and its prognosis will dicondições de cumprir o prolongado e intenso programa de

rectly depend on the time frame that the humeral head had

fisioterapia que se segue à cirurgia: alcoólatras, epilépticos e

lost its relation with the glenoid.

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

3

M.A. CASTRO VEADO

A

Fig. 2 – A) Paciente com uma luxação anterior crônica não reduzida

há mais de cinco

anos, assintomática; B) Aspecto

radiológico.

B

Fig. 2 – A) Asymptomatic patient

with chronic anterior dislocation

for more than five

years. B) Radiological aspect.

aqueles com baixo nível social costumam não ser cooperativos.

O tipo de cirurgia realizada e seu prognóstico vão depender diretamente do tempo que a cabeça umeral perdeu sua

relação com a glenóide.

O tamanho e a localização dos defeitos da cabeça, perdas

ósseas na glenóide e lesões do manguito rotador, principalmente a do tendão do músculo subescapular, devem ser cuidadosamente avaliados para que um adequado planejamento

operatório seja feito(1).

4

Fig. 3 – Radiografia em AP do ombro mostrando uma lesão de

Hill-Sachs

Fig. 3 – Shoulder AP X-ray showing Hill-Sachs lesion

Head bone defects size and location, glenoid bone loss and

rotator cuff injuries – mainly the subscapularis muscle – must

be carefully assessed for an adequate preoperative planning(1).

CHRONIC ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

Shoulder anterior dislocation is one of the most familiar

injuries to the orthopedic surgeon, and the diagnosis seldom

goes unnoticed if seen during the acute phase. As previously

mentioned, patients with mental state alteration or carriers

of unknown seizures may deny important information about

timing and cause of the injury.

It is not difficult to find that the humeral head is out of the

glenoid, viewed from an anteroposterior X-ray incidence. The

posterolateral humeral head defect (Hill-Sachs lesion) may

be sufficiently large in long standing cases (figure 3). As time

goes by, there is a “false” glenoid formation within the scapular anterior neck, where the dislocated humeral head is(2,3).

The axillary X-ray view seals the diagnosis of dislocation

direction(1,2,5,11) and, when associated to computerized tomography, it may show glenoid fractures and humeral head defect size(1,2,3,8).

Magnetic resonance imaging is not needed for those cases,

but it helps to check the subscapularis muscle tendon status,

as it is the main passive stabilizer on the anterior dislocation.

Sometimes after reduction of the anterior dislocation, it

recurs due to an anterior glenoid rim fracture, a situation

that may not be diagnosed, especially in the aged and osteoporotic(2,3,8) (figure 4).

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

LUXAÇÃO ANTERIOR CRÔNICA

A luxação anterior do ombro é das lesões mais familiares

ao ortopedista e o diagnóstico dificilmente passa despercebido se visto na fase aguda. Como dito anteriormente, pacientes

com estado mental alterado ou portadores de crise convulsiva

não conhecida podem sonegar informações importantes em

relação ao tempo e causa da lesão.

Com uma radiografia feita em AP no plano do corpo não é

difícil perceber que a cabeça umeral encontra-se fora da glenóide. O defeito póstero-lateral na cabeça umeral (lesão de

Hill-Sachs) pode ser bastante grande em casos de longa duração (fig. 3). Com o tempo, forma-se uma “falsa” glenóide no

colo anterior da escápula, que está em contato com a cabeça

deslocada(2,3).

A radiografia axilar é definitiva para o diagnóstico da direção da luxação(1,2,5,11) quando associada à tomografia computadorizada, pode mostrar fraturas da glenóide e dimensionar

o defeito da cabeça umeral(1,2,3,8).

A ressonância magnética é dispensável nesses casos, mas

ajuda a verificar o estado do tendão do músculo subescapular,

já que ele é o principal estabilizador passivo na luxação anterior.

Algumas vezes, após a redução da luxação anterior, esta se

refaz em função da presença de fratura da borda anterior da

glenóide, situação que pode não ser diagnosticada, principalmente nos idosos osteoporóticos2,3,8 (fig. 4).

Em presença de lesão nervosa concomitante, particularmente do nervo axilar, é necessário documentá-la, se possível com

eletroneuromiografia, comunicando a complicação ao paciente

antes da realização de qualquer procedimento.

TRATAMENTO DA LUXAÇÃO

ANTERIOR CRÔNICA

O tratamento dessa condição pode variar desde uma conduta expectante, passando pela redução aberta com reconstrução articular e enxerto ósseo, chegando até mesmo à artroplastia.

Uma clara e sincera conversa com o paciente e familiares

deve acontecer a fim de mostrar-lhes a difícil situação a enfrentar.

O desafio maior é o de escolher o tipo de procedimento

mais adequado para cada paciente.

Às vezes, o melhor é não fazer nada, apesar de o deslocamento anterior crônico ser mal tolerado pelo paciente quando

comparado com o posterior. Neste, ele consegue alcançar a

face e a boca devido à contratura fixa do membro em rotação

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

A

C

B

D

Fig. 4 – A) Radiografia em AP mostrando uma luxação anterior

associada a uma fratura da borda anterior da escápula. B) Tomografia computadorizada. Feita redução incruenta da luxação com

perda posteriormente dentro do Velpeau. C e D) Redução aberta

e preenchimento do defeito ósseo com o processo coracóide três

meses após o trauma.

Fig. 4 – A) AP X-ray showing anterior dislocation associated to

anterior scapular rim fracture. B) Computerized tomography.

Closed reduction of dislocation and further loss of reduction within

Velpeau immobilization. C and D) Open reduction and bone defect filling with coracoid process three months after the trauma.

In presence of a concurrent nerve injury, particularly the

axillary nerve, it is necessary to document the lesion with an

electromyography, telling the patient about the complication

before any procedure is performed.

TREATMENT OF CHRONIC

ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

The treatment of this condition may range from simply waiting to open reduction, and joint reconstruction to arthroplasty.

5

M.A. CASTRO VEADO

interna; na luxação anterior, o braço está fixo, afastado do

corpo e em rotação externa, situação que é mais incapacitante(6).

Redução fechada – Pode ser tentada com muita cautela

através de manipulação suave, estando o paciente com anestesia venosa e com bom relaxamento, até no máximo duas a

três semanas após a lesão. Segundo Matsen e Rockwood, se a

lesão data de uma semana ou mais, a redução fechada não

deve ser tentada porque a contratura de partes moles é tão

intensa que aumenta muito o risco de fratura no úmero(8). Nos

idosos os riscos são ainda maiores devido à menor elasticidade da parede das artérias e à osteoporose(6).

Nossa experiência é não insistir na redução de uma luxação com mais de duas semanas ou com data de ocorrência

mal definida.

Redução aberta – Deve ser realizada em luxações bloqueadas nas quais a tentativa de redução fechada não obteve

êxito. Até provavelmente seis meses considera-se a cartilagem ainda como preservada, sendo possível a reconstrução

articular. Nos casos mais graves é prudente deixar sempre um

cirurgião vascular de sobre-aviso, pois a intensa fibrose e a

anatomia alterada aumentam muito o risco de lesão dos vasos

axilares.

Preferimos o acesso deltopeitoral longo com o paciente na

posição de “cadeira de praia”. Liberação de parte da inserção

do peitoral maior, do músculo subescapular e da cápsula articular contraturada deve ser realizada, ao mesmo tempo que

ganhamos mais rotação externa, facilitando assim a capsulotomia posterior, num procedimento praticamente circunferencial. A ligadura da artéria umeral circunflexa anterior pode

ser necessária, bem como a visualização e proteção do nervo

axilar. Todo o conteúdo fibrótico da cavidade glenóide deve

ser removido para que a cabeça umeral possa ser adequadamente reduzida.

Após a redução, avaliamos a estabilidade da articulação,

isto é, a quantidade de rotação interna necessária para manter

a cabeça reduzida.

Alguns preferem a estabilização temporária com fios ou

parafusos(6,12) fixando-se a articulação glenoumeral ou o acrômio ao úmero, procedimentos criticados por Flatow et al(3).

Eles acham que, se é necessário o uso desses fios, é porque a

liberação não foi suficiente, o que facilitará a reluxação após

a retirada dos mesmos(2,3). Além do mais, os fios ou parafusos

causam dano à articulação (fig. 5).

Após a redução cirúrgica, tem sido a nossa preferência realizar a cirurgia de Bristow para evitar a luxação recidivante,

ao invés de procedermos ao reparo da lesão de Bankart. As

6

A direct and sincere talk with the patient and family must

take place to show the difficult situation they face.

A main challenge is to choose the most adequate type of

procedure for each patient.

Sometimes the best is to do nothing, despite that the chronic anterior dislocation is not as well tolerated as the posterior

dislocation by the patient. In the posterior dislocation, the

patient may reach the face and the mouth due to upper limb

fixed internal rotation, whereas in the anterior dislocation

the arm is fixed, away from the body, and in external rotation,

a more disabling situation(6).

Closed reduction – It may be carefully attempted by gentle

manipulation, having the patient under IV anesthesia and

adequate muscle relaxation, at the most within two to three

weeks after the injury. According to Matsen and Rockwood, if

the injury is older than one week or more, closed reduction

should not to be attempted, as soft tissue contracture is so

intense that it increases the risk of humeral fracture(8). In aged,

the risks are even higher due to lesser arterial wall elasticity

and osteoporosis(6).

In our experience, we do not insist on the reduction of a

dislocation with more than two weeks or an ill-defined occurrence date.

Open reduction – The attempt of closed reduction must be

performed in blocked dislocations, when a closed reduction

attempt had not succeeded. The cartilage is considered to be

preserved probably until six months, making possible the joint

reconstruction. In most serious cases, it is advisable to have a

vascular surgeon at hand, as the intense scarring and the modified anatomy largely increases the risk of axillary vessel injury.

We prefer the long deltopectoral approach, with the patient

on the beach chair position. A practically circumferential procedure is performed by the partial release of the pectoralis

major muscle, subscapularis muscle, and contracted joint

capsule insertions, at the same time that we get more external

rotation, thus facilitating a posterior capsulotomy. Anterior

humeral circumflex artery ligature may be necessary, as well

as axillary nerve viewing and protection. All glenoid cavity

fibrous content must be removed, so that the humeral head

can be adequately reduced.

After reduction, we assess joint stability, that is, the necessary amount of internal rotation to keep the head reduced.

Some favor temporary stabilization with wires or screws(6,12)

for glenohumeral joint or acromiohumeral fixation; Flattow

et al criticized both procedures(3). They found that the use of

those wires is explained due to an insufficient release, which

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

A

B

Fig. 5 – A e B) Sexo masc., 43 anos, há oito meses com dor e

grande limitação de movimentos do ombro após crise de abstinência alcoólica. Pós-operatório: redução aberta instável (Bristow) e fixação com um fio de Steinmann.

Fig. 5 – A and B) Male, 43 years, with pain and great shoulder

range of motion limitation after alcohol withdrawal. Postoperative: unstable open reduction (Bristow), and Steinmann pin fixation.

grandes lesões de Hill-Sachs, maiores que 40% de defeito do

canto póstero-superior, facilitam a reluxação mesmo com pouca amplitude de rotação externa. Nesses casos, as reconstruções são necessárias.

As osteotomias rotacionais foram preconizadas pelo Grupo AO, mas somente para a instabilidade recidivante(13). Na

luxação crônica não existe nada publicado.

As ressecções da cabeça umeral não têm lugar como procedimento de primeira escolha, uma vez que as artroplastias

vieram para cobrir essa deficiência.

Naqueles com luxações mais antigas – com seis meses ou

mais – e com defeitos maiores que 40% da superfície articular, as artroplastias constituem a melhor opção, pois a cabeça

torna-se osteopênica e se achatará após a redução (cabeça tipo

bola de pingue-pongue)(1,2,3).

A maior complicação da prótese é a tendência para a luxação anterior. Nesses casos, aumento na retroversão é imprescindível(10,11).

Quando existe desgaste importante da glenóide anterior, é

necessário proceder ao abaixamento da glenóide posterior (2,3).

O osso ressecado da cabeça umeral pode também ser usado

como enxerto para aumentar a glenóide anterior. Se a cartilagem da glenóide está em boas condições, alguns associam à

hemiartroplastia, um reparo capsular semelhante ao reparo de

Bankart, para dar mais estabilidade à articulação(1).

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

will later facilitate a redislocation upon wire removal(2,3). In

addition, wires or screws damage the joint (figure 5).

After the surgical reduction, there has been our preference

to perform Bristow’s procedure to prevent the recurrent dislocation, instead of performing Bankart’s repair. Larger HillSachs injuries, consisting of more than 40% of posterosuperior corner defects, facilitate redislocation even at a little range

of external rotation. In those cases, reconstructions are necessary.

The rotational osteotomies had been advocated by AO

Group, but only for recurring instability(13). There is nothing

published for chronic dislocation.

Humeral head resections do not take place as first-line procedures, as arthroplasties had come to replace that deficiency.

Patients with older dislocations – six months or more – and

joint surface defects in excess of 40% form the best option for

arthroplasties, as the head becomes osteopenic and will flatten after reduction (ping-pong ball head)(1,2,3).

The prosthesis most important complication is the trend for

anterior dislocation. In those cases, a retroversion increase is

essential(10,11).

It is necessary to do a posterior glenoid lowering if there is

an important anterior glenoid wearing(2,3). Resected humeral

head bone can also be used as a graft to increase the anterior

glenoid. If the glenoid cartilage is in good condition, the hemiarthroplasty is associated by some experts to a capsule repair

similar to Bankart’s repair to increase joint stability(1).

Our opinion is that only a prosthetic version change along

with capsule tensioning is enough to provide adequate joint

stability.

If the subscapularis is torn, it should be mobilized and sutured. We do not have experience with calcaneal tendon grafts.

Despite complex joint reconstructions, sometimes results are

not satisfactory, and the patient may evolve with an important

loss of motion.

CHRONIC POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

McLaughlin defined that “the posterior dislocation is a trap

to the inattentive surgeon”, although its signs and symptoms

are constant and unequivocal(14).

Cooper stated that physical findings are so obvious that [it

consists of] “a lesion that shall not be confused”(8).

Neer and Hawkins reported a mean delay of one year for

the posterior dislocation diagnosis(14).

Elderly patients present more subtle symptoms, often with

diagnostic delay.

7

M.A. CASTRO VEADO

Somos da opinião de que somente uma alteração na versão

da prótese, juntamente com maior tensionamento capsular, é

suficiente para conferir boa estabilidade à articulação.

Se o subescapular está rompido, este deve ser mobilizado e

suturado. Não temos experiências com enxertos usando o tendão-de-aquiles. Apesar das complexas reconstruções articulares, os resultados nem sempre são bons, podendo o paciente

evoluir com perda importante dos movimentos.

LUXAÇÃO POSTERIOR CRÔNICA

Segundo Hawkins e Cash, McLaughlin considerava “a luxação posterior uma armadilha para o cirurgião distraído”,

embora os sinais e sintomas sejam constantes e inequívocos(14).

Segundo Matsen e Rockwood, Cooper afirmou que os achados físicos são tão óbvios, que “é uma lesão que não pode ser

confundida”(8).

Neer e Hawkins relataram atraso em média de um ano no

diagnóstico da luxação posterior (14).

Nos idosos os sintomas são mais sutis, atrasando freqüentemente o diagnóstico.

A incidência da luxação escapuloumeral posterior é estimada em 2%, mas provavelmente é muito maior, devido à

elevada ocorrência de casos não reconhecidos(8).

Rowe e Zarins, em 1982, relataram que o diagnóstico não

foi feito em 79% dos seus casos(6).

Essa lesão pode resultar de queda com a mão espalmada

com uma força aplicada sobre o ombro em flexão, adução e

rotação interna, ou após crise convulsiva, devido ao predomínio dos rotadores internos mais potentes.

Hipoglicemia noturna pode provocar convulsão sem que o

paciente perceba o que realmente aconteceu. Suspeitar sempre de luxação posterior crônica nos casos em tratamento prolongado de capsulite adesiva do ombro resistente ao tratamento

conservador (2).

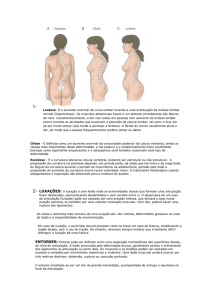

Com o exame físico semiologicamente bem feito, a lesão

torna-se evidente pela perda ou ausência completa da rotação

interna (sinal importante para o diagnóstico), proeminência

do processo coracóide, enchimento posterior do ombro quando observado de cima ou de trás, mau alinhamento do braço

quando visto de lado. A elevação anterior e a rotação interna,

embora limitadas, às vezes surpreendem(14).

Rowe e Zarins descreveram um sinal físico típico: o paciente é incapaz de girar a palma da mão para cima com o

lado afetado(6) (fig. 6).

Radiografia feita somente em AP é a grande cilada, pois

freqüentemente é dada como normal, apesar de haver vários

sinais sugestivos de luxação, perda da sombra eliptiforme da

8

Fig. 6 – Sinal

de Carter Rowe:

incapacidade de

girar a palma da

mão para cima

(perda da

rotação externa).

Fig. 6 – Carter

Rowe sign:

inability to turn

the palm

towards the

ceiling (loss of

external

rotation).

The incidence of the posterior glenohumeral dislocation is

estimated around 2%, but it is probably much higher due to a

high number of unrecognized cases(8).

Rowe and Zarins in 1982 reported that the diagnosis was

not achieved in 79% of their cases(6).

This injury may result of a fall on the outstretched hand

with a force applied towards the shoulder in flexion, adduction, and internal rotation, or after seizures, due to the predominance of the more powerful internal rotators.

Nocturnal hypoglycemia may provoke seizures without the

patient’s perception of what really happened. There must always be a high suspicion degree of chronic posterior dislocation in those cases of protracted treatment of adhesive capsulitis that are resistant to conservative treatment(2).

A semiologically adequate physical examination unveils the

lesion for the evidence of complete internal rotation loss or

absence (an important diagnostic sign), coracoid process

prominence, posterior shoulder filling upon the observation

from above or from the back, and arm malalignment upon

lateral observation. Although limited, anterior elevation and

internal rotation are sometimes surprising(14).

Rowe described a typical physical sign: the patient is unable to turn his/her palm of the hand towards the ceiling with

the affected side(6) (figure 6).

Frequently considered as normal despite the presence of

several suggestive dislocation signs, such as an elliptical gleRev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

Fig. 8

Tomografia

computadorizada

exibindo uma

luxação

posterior

associada à

fratura da

glenóide

Fig. 8

Computerized

tomography

showing a

posterior

dislocation

associated to

glenoid fracture

Fig. 7

Radiografia

em AP

sugerindo um

deslocamento

posterior da

cabeça umeral

Fig. 7 – AP X-ray

suggesting

a posterior

humeral head

displacement

glenóide, aumento do espaço entre a parte medial da cabeça

umeral e a borda anterior da glenóide, e o úmero em rotação

interna(14) (fig. 7).

A radiografia transaxilar é imperativa, não só para confirmar o diagnóstico, mas também para dar idéia do tamanho do

defeito ântero-medial da cabeça umeral (Hill-Sachs reverso)

e das fraturas da glenóide associadas. Na prática, é negligenciada com certa freqüência, seja por desconhecimento, incúria, ou mesmo pela dificuldade e receio que os técnicos têm

em posicionar adequadamente o braço.

A tomografia computadorizada é importante para melhor

definição do tamanho do defeito e para identificar lesões articulares associadas.

Tem sido relatado que, em torno de 50% das luxações posteriores, existe uma fratura do colo cirúrgico ou da escápula

associada(1) (fig. 8). Nas luxações anteriores esse quadro não

é tão comum. A presença dessas fraturas precisa ser conhecida antes que qualquer conduta seja tomada.

A

C

D

B

E

F

Fig. 9 – A) Em qual dos lados essa paciente foi operada? B) Radiografia em axilar do ombro esquerdo não operado (assintomático). C e D) Radiografia em AP e axilar do ombro direito com fratura-luxação posterior. E e F) Hemiartroplastia realizada dois meses

após a lesão.

TRATAMENTO

Fig. 9 – A) What side did this patient operate? B) Axillary view of

non-operated left shoulder (asymptomatic). C and D) Right shoulder AP and axillary X-rays showing posterior fracture-dislocation.

E and F) Hemiarthroplasty performed two months after the lesion.

Em muitas situações, um quadro radiológico alarmante

mostrando grande incongruência articular contrasta enormemente com o quadro clínico do paciente, que exibe amplitude

de movimentos bastante razoável e com pouca ou nenhuma

dor (fig. 9).

noid shadow, increase of space between the medial part of the

humeral head and the anterior glenoid rim, and humerus internal rotation, an isolated AP X-ray is grossly inaccurate(14)

(figure 7).

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

9

M.A. CASTRO VEADO

Em 1987, Hawkins et al publicaram sua experiência com

41 pacientes portadores de luxação posterior com seguimento de cinco anos e meio. Sete deles recusaram-se a receber

qualquer tipo de tratamento(15). Pacientes mais idosos com demanda limitada, capazes de alcançar a boca e com o ombro

contralateral funcionante, merecem ser observados. Não operamos também os com episódios de crise convulsiva não controlada ou os pouco cooperativos com o tratamento pós-operatório e de reabilitação. Reconstruções cirúrgicas devem ser

reservadas para os pacientes com bom estoque ósseo e grande

incapacidade funcional(1).

Redução fechada – Após quanto tempo da lesão estaremos autorizados a tentar a redução com segurança?

Não existe aqui também concordância entre os autores.

Segundo Matsen e Rockwood, Hawkins et al tentaram a redução em seus 12 pacientes com menos de seis semanas de

evolução e tiveram êxito em três(8). Schultz et al conseguiram a

redução em três dos 17 casos com menos de quatro semanas(4).

Acreditamos que, se a luxação tem menos que quatro semanas e defeito na cabeça umeral menor que 20%, a redução

incruenta pode ser tentada.

A tentativa de redução somente deve ser feita sob anestesia

geral, com bom relaxamento muscular, tração suave e sem

manobras tipo alavanca. Pode ser necessário relaxar o manguito posterior e a cápsula. Para isso, devemos rodar ao máximo o úmero internamente antes de tentar a redução, e associar tração lateral. Não rodar externamente antes de a redução

ser obtida, devido ao alto risco de fraturar a cabeça ou a diáfise umeral(8).

Conseguida, a redução, é necessário testar a estabilidade

da articulação, avaliando se a amplitude da rotação externa é

necessária para manter a cabeça reduzida. Em seguida, o membro superior envolvido é imobilizado em leve abdução e rotação externa de até 20° por período de seis semanas(1).

Se o tratamento incruento falhar, estará indicada a redução

aberta, após minuciosa análise do paciente no que se refere a

dor, perda de movimento, qualidade óssea e disponibilidade

para reabilitação.

Redução aberta – É executada com o paciente sob anestesia, na posição conhecida como “cadeira de praia”. Após acesso

pelo intervalo deltopeitoral, identificamos o cabo longo do

bíceps, para então localizarmos a pequena tuberosidade com

o tendão do subescapular inserido. Este pode ser liberado com

osteotomia da pequena tuberosidade ou sem ela(1,14,16).

A glenóide deve ser esvaziada do seu conteúdo fibrótico

antes da redução e inspecionada em busca de defeitos articulares.

10

The transaxillary X-ray is imperative not only to confirm

the diagnosis, but also to provide an idea about the humeral

head anteromedial defect size (reversed Hill-Sachs) and associated glenoid fractures. In practice, it is eventually neglected, either by lack of knowledge, negligence, or even due to

difficulty and fear that technicians have to adequately position the arm.

Computerized tomography is important for a better definition of defect size and to identify associated joint lesions.

It has been reported that around 50% of posterior dislocations carry an associated fracture of the surgical neck or scapula(1) (figure 8). Such picture is not so common in anterior

dislocations. The presence of those fractures must be recognized before taking any other steps.

TREATMENT

In many situations, an alarming radiological picture with

gross incongruity largely contrasts with the patient’s clinical

picture, who exhibits a quite reasonable range of motion and

little or no pain (figure 9).

In 1987, Hawkins et al published their series with 41 patients who presented a posterior dislocation, followed up for

5.5 years. Seven patients refused to receive any treatment

type(15). Older patients, with limited demands and able to reach

the mouth with the contralateral functioning shoulder, should

be observed. We do not operate patients with uncontrolled

seizures or those who may have low postoperative and rehabilitation compliance. Surgical reconstructions should be reserved for patients with adequate bone stock and severe functional impairment(1).

Closed reduction – How long after the injury are we entitled to attempt a safe reduction?

There is not an agreement among the authors. Hawkins et

al attempted a reduction for their 12 patients with less than

six weeks of evolution, and succeeded in three patients(8).

Schultz et al achieved reduction in three of 17 cases with less

than four weeks(4).

We believe that the closed reduction may be attempted if

the dislocation is less than four weeks old, with a humeral

head defect of less than 20%.

Reduction attempt must only be performed under general

anesthesia, with adequate muscle relaxation, gentle traction,

and with no lever-like maneuvers. It may be needed to relax

the posterior cuff and the capsule. For this purpose, we should

maximally internally rotate the humerus before reduction attempt, with lateral traction associated. Do not externally roRev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

Fig. 10

Radiografia em

AP: cirurgia de

McLaughlin

modificada

por Neer.

Fig. 10

AP X-ray:

McLaughlin’s

procedure

modified

by Neer.

Tração é feita com a ajuda de um gancho, puxando-se a

diáfise umeral lateralmente antes de empurrar a cabeça por

meio de força aplicada de trás para diante em direção à glenóide.

Não alavancar o úmero na hora da redução, pois a cartilagem articular pode estar muito amolecida.

Em seguida, avaliamos o tamanho do defeito da cabeça

umeral. Se a articulação é instável e o defeito menor que 40%

da superfície articular, a melhor conduta é transferir o subescapular para o interior do defeito. Nos pacientes com boa qualidade óssea, optamos por osteotomizar a pequena tuberosidade e fixá-la com um ou dois parafusos maleolares associados

a uma arruela, para minimizar a possibilidade de fragmentação do osso (fig. 10). Nos mais idosos soltamos o subescapular com uma capa óssea, para apressar a consolidação e dar

mais segurança na fixação, a qual é feita com sutura não absorvível. Às vezes, utilizamos âncoras para a fixação do tendão do subescapular. Sempre cruentizamos o leito receptor

antes da fixação do tendão.

Se existir fratura associada, provavelmente a melhor opção

será a redução aberta com fixação da fratura.

A lesão da cápsula posterior ou pequenas fraturas da glenóide posterior raramente necessitam de tratamento além de

um simples desbridamento.

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

tate before reduction accomplishment due to the risk of humeral head or diaphyseal fracture(8).

The joint stability should be tested after reduction accomplished, assessing external rotation range, needed to keep the

head reduced. Then, the upper limb is immobilized in slight

abduction and external rotation of no more than 20° for a

period of six weeks(1).

If closed treatment fails, open reduction is indicated after

careful patient assessment of pain, loss of motion, bone stock,

and rehabilitation availability.

Open reduction – It is performed with the patient on a beach

chair position, under general anesthetic. After deltopectoral

approach, we identify biceps long head to locate the lesser

tubercle where the subscapularis tendon is inserted. It may be

released with or without a lesser tubercle osteotomy(1,14,16).

Glenoid scarring must be removed and inspected for joint

defects before reduction.

Traction is performed by a hook laterally pulling the humeral shaft before humeral head is pushed towards the glenoid with a back to front force.

Do not lever the humerus during reduction, as the joint

cartilage may be too soft.

The humeral head defect size is then assessed. If the joint is

unstable and the defect corresponds to less than 40% of joint

surface, the best treatment is to transfer the subscapularis

tendon to the inner part of the defect. In patients with adequate bone stock, our option is a lesser tubercle osteotomy

fixation with one or two malleolar screws with washers aiming to minimize the possibility of bone fragmentation (figure

10). In the elderly we release the subscapularis with a bone

coating to enhance healing and to provide a more secure fixation, performed with non-absorbable sutures. We sometimes

employ bone anchors for subscapularis tendon fixation, and

always leave a bleeding bone surface before tendon fixation.

If there is an associated fracture, probably the best option

is the open reduction and fracture fixation.

Posterior capsule lesions or posterior glenoid fracture seldom need other treatment then a simple debridement.

According to Loenberg and Cuomo, Keppler and Holz in

1994 advocated a humeral surgical neck rotational osteotomy and angled plate fixation only for those cases with less

than 40% of involvement of joint surface. Of ten patients, six

presented excellent and good results, two patients had reasonable results, and two patients had poor results(1). The advantage would be the absence of prolonged postoperative

immobilization, although adding a new bone aggression –

the osteotomy – which may pose an additional complication.

11

M.A. CASTRO VEADO

Segundo Loenberg e CuoA

mo, foram Keppler e Holz, em

1994, que preconizaram osteotomia rotacional no colo cirúrgico do úmero e fixação

com placa angulada, somente

nos casos com lesão menor

que 40% da superfície articular. Em 10 pacientes, seis tiveram excelentes e bons resultados, dois razoáveis e dois

pobres(1). A vantagem é a dispensa de imobilização prolongada no pós-operatório, emboB

ra acrescente nova agressão

óssea – osteotomia – que pode

ser fator adicional de complicação. Além do mais, a placa

exige maior desperiostização,

com maior risco de infecção e

retardo de consolidação ou

não consolidação.

Gerber e Lambert propõem,

nas lesões menores que 50%

e em ossos de boa qualidade,

o preenchimento da cavidade

com enxerto retirado da cabeça femoral e fixação por parafuso esponjoso(17). Seus resultados são semelhantes aos do

procedimento de McLaughlin

modificado por Neer, como relataram Gerber e Lambert(17).

Se o defeito é maior que

45% da superfície articular,

visto na radiografia transaxilar, com glenóide normal, a hemiartroplastia é a indicação de escolha da maioria dos cirurgiões(18).

Se a glenóide está comprometida, a artroplastia total é melhor opção.

O detalhe técnico fundamental é tirar a retroversão do componente umeral para diminuir a tendência da cabeça umeral

de deslocar-se posteriormente. Quanto mais tempo a cabeça

permanecer luxada posteriormente, menos retroversão deve

ser colocada(11,14,18).

Plicatura da cápsula posterior, após a osteotomia da cabeça

umeral e antes da inserção da prótese definitiva, pode ser ne12

Furthermore, the plate requires more periosteal stripping, a higher chance of infection, delayed union, and

nonunion.

Gerber and Lambert proposed cavity filling with femoral head graft and cancellous screw fixation in lesions

lesser than 50% and good

bone stock(17). Their results

are similar to McLaughlin’s

procedure modified by Neer,

Fig. 11

as reported by Gerber and

A) Tentativa

Lambert(14).

de redução

Most surgeons choose

cirúrgica de

uma luxação

hemiarthroplasty if the defect

posterior.

is in excess of 45% on the

B) Fixação

transaxillary view, with a

da grande

tuberosidade

normal glenoid. Upon glesem redução da

noid compromising, the best

luxação anterior.

option is the total arthroplasFig. 11

ty.

A) A surgical

reduction

The removal of humeral

attempt of a

component retroversion is an

posterior

essential technical detail to

dislocation.

lessen the humeral head

B) Greater

tubercle fixation

trend for posterior displacewithout anterior

ment. The longer the head

dislocation

remains posteriorly dislocatreduction.

ed, the lesser retroversion

should be placed(11,14,18).

A posterior capsule plication after humeral head osteotomy and before definite

prosthetic placement may be needed for final adjustments. It

is sometimes recommended to immobilize the upper limb in

slight abduction and external rotation to confer more stability and for plication protection(11).

Once the diagnosis is performed, the surgeon must be acquainted with the severity of the lesion, should know the surgical approach, and ought to have adequate surgical team

and material if he or she decides to operate an unreduced

dislocation. True catastrophes may arise when the surgeon is

not fully acquainted with such lesion (figure 11).

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

LUXAÇÃO INVETERADA DO OMBRO

cessária para os ajustes finais. Às vezes, é recomendado imobilizar o membro em leve abdução e rotação externa para dar

mais estabilidade e proteger a plicatura(11).

Uma vez feito o diagnóstico, o cirurgião que se propõe a

operar uma luxação inveterada deve estar ciente da gravidade

dessas lesões, conhecer a abordagem cirúrgica e ter equipe e

material cirúrgico adequados.

Verdadeiras catástrofes podem acontecer quando o cirurgião tem pouca intimidade com esse tipo de lesão (fig. 11).

REFERÊNCIAS / REFERENCES

1. Loebenberg M.I., Cuomo F.: The treatment of chronic anterior and posterior dislocations of the glenohumeral joint and associated articular surface

defects. Orthop Clin North Am 31: 23-34, 2000.

2. Deliz E.D., Flatow E.L.: “Chronic unreduced shoulder dislocations”. In:

Bigliani L.U.: Complications of shoulder surgery. Maryland, Williams and

Wilkins, p. 127-138, 1993.

3. Flatow E.L., Miller S.R., Neer C.S.: Chronic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2: 2-10, 1993.

4. Schultz T., Jacobs B., Patterson R.L.: Unrecognized dislocations of the shoulder. J Trauma 9: 1009-1023, 1969.

5. Postacchini F., Facchini M.: The treatment of unreduced dislocation of the

shoulder. A review of 12 cases. J Orthop Traumatol 13: 15-26, 1987.

6. Rowe C., Zarins B.: Chronic unreduced dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone

Joint Surg [Am] 64: 494-505, 1982.

7. Buhler M., Gerber C.: Shoulder instability related to epileptic seizures. J

Shoulder Elbow Surg 11: 339-343, 2002.

8. Matsen F.A., Rockwood C.A.: “Anterior glenohumeral instability”. In:

Roockwood C.A., Matsen F.A.: The shoulder. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders,

p. 671-672, 1990.

9. Lech O: Fundamentos em Cirurgia do Ombro. São Paulo, Harbra, 100,

1995.

Rev Bras Ortop _ Vol. 39, Nos 1/2 – Jan/Fev, 2004

10. Pritchett J.W., Clark J.M.: Prosthetic replacement for chronic unreduced

dislocations of the shoulder. Clin Orthop 216: 89-93, 1987.

11. Zuckerman J.D.: McLaughlin Procedure for Acute and Chronic Posterior

Dislocations in Master Techniques in Orthopaedics Surgery. The Shoulder.

Craig EV. New York, Raven Press, p. 165-180, 1995.

12. Neviaser J.S.: The treatment of old unreduced dislocations of the shoulder.

Surg Clin North Am 43:1671-1678, 1963.

13. Weber B.G., Simpson L.A., Hardegger F.: Rotational osteotomy for the recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder associated with a large Hill-Sachs lesion. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 66: 1443-1449, 1984.

14. Hawkins R.J., Cash J.D.: “Complications of posterior instability repairs”.

In: Bigliani L.U.: Complications of shoulder surgery. Maryland, Williams

and Wilkins, p. 117-126, 1993.

15. Hawkins R.J., Neer C.S., Pianta R.M., et al: Locked posterior dislocation of

the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 69: 9-18, 1987.

16. Mestdagh H., Maynou C., et al: Traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Ann Chir 48: 355-363, 1994.

17. Gerber C., Lambert S.M.: Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects in

humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of

the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 78: 376-382, 1996.

18. Walch R., Boileau P., Martin B., Dejour H.: Unreduced posterior luxations

and fractures-luxations of the shoulder. Rev Chir Orthop 76: 546-558, 1990.

13