UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DO AMAZONAS

FUNDAÇÃO DE MEDICINA TROPICAL DR. HEITOR VIEIRA DOURADO

PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MEDICINA TROPICAL

DOUTORADO EM DOENÇAS TROPICAIS E INFECCIOSAS

AS COINFECÇÕES VIRAIS E O PERFIL IMUNOLÓGICO DE PACIENTES HIV

POSITIVOS PORTADORES DE NEOPLASIA INTRAEPITELIAL ANAL

ADRIANA GONÇALVES DAUMAS PINHEIRO GUIMARÃES

MANAUS

2014

i

ADRIANA GONÇALVES DAUMAS PINHEIRO GUIMARÃES

AS COINFECÇÕES VIRAIS E O PERFIL IMUNOLÓGICO DE PACIENTES HIV

POSITIVOS PORTADORES DE NEOPLASIA INTRAEPITELIAL ANAL

Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação

em Medicina Tropical da Universidade do Estado do

Amazonas, para obtenção do grau de Doutor em

Doenças Tropicais e Infecciosas.

Orientador: Prof°. Dr. Luiz Carlos de Lima Ferreira

Co-Orientador: Profª. Dra. Adriana Malheiro

MANAUS

2014

G963a

Guimarães, Adriana Gonçalves Daumas Pinheiro.

As coinfecções virais e o perfil imunológico de pacientes

HIV positivos portadores de neoplasia intraepitelial anal /

Adriana Gonçalves Daumas Pinheiro Guimarães. -- Manaus :

Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, UFAM, 2014.

45 f. : il.

Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós Graduação em Medicina Tropical da

Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, 2014.

Orientador: Prof°. Dr. Luiz Carlos de Lima Ferreira

Co-Orientador: Profa. Dra. Adriana Malheiro

1. Virus – HIV 2.Coinfecção anal 3. Perfil imunológico –

Paciente – HIV I. Título.

CDU: 616.98

Ficha Catalográfica elaborada pela Bibliotecária. Sheyla Lobo Mota.

CRB: 484

ii

FOLHA DE JULGAMENTO

AS COINFECÇÕES VIRAIS E O PERFIL IMUNOLÓGICO DE PACIENTES

HIV POSITIVOS PORTADORES DE NEOPLASIA INTRAEPITELIAL ANAL

ADRIANA GONÇALVES DAUMAS PINHEIRO GUIMARÃES

“Esta tese foi julgada adequada para obtenção do Título de Doutor em Doenças

Tropicais e Infecciosas, aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de PósGraduação em Medicina Tropical da Universidade do Estado do Amazonas em

convênio com a Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado”.

Banca Julgadora:

Prof. Luiz Carlos de Lima Ferreira, Dr. Presidente

Prof. Marcelo Cordeiro dos Santos, Dr. Membro

Prof. João Vicente Braga de Souza, Dr. Membro

Prof. Carmem Ruth Mazione Nadal, Dr. Membro

Prof. Olindo Assis Martins Filho, Dr. Membro

iii

DEDICATÓRIA

Aos meus amores:

José Jorge Pinheiro Guimarães

Paulo Daumas Kale Martins

Roberta Daumas Kale Martins

Bárbara Daumas Kale Martins

iv

AGRADECIMENTOS

Aos pacientes que se doam à pesquisa na esperança de alcançarem a cura para suas

dores nem sempre físicas, nem sempre abordáveis.

Aos orientadores Prof. Dr. Luiz Carlos de Lima Ferreira e Prof. Dra. Adriana Malheiro

pelo estímulo, apoio, disponibilidade e por acreditarem em mim.

Aos colegas patologistas da FMTHVD José Ribamar de Araújo e Rosilene Viana de

Andrade pelo apoio, carinho e esntusiasmos com o qual sempre trataram minha

pesquisa.

A técnica de enfermagem Elizabeth Monteiro, pela dedicação, pelo amor aos pacientes,

por se doar a esta pesquisa e por sestar sempre pronta a ajudar.

Os autores agradecem ao Dr Leandro Baldino, aos estudantes de medicina Aline Lury

Hada, Bruno Queiroz e Isabelle Gracinda Aguiar; aos farmacêuticos Andreza Fernandes,

Carolina Marinho e Cristiana Lima Laranjeira.

Aos técnicos da patologia da FMT-HVD, Sandra Caranhas, Carlos Melquiades Marques,

Sandra Eline e Sra. Maria Araújo pela ajuda incondicional e por sempre me acolherem

com um soriso.

A toda a equipe de suporte hospitalar da FMT-HVD pelo carinho e suporte indispensável

a conclusão deste estudo.

A Secretaria Estadual de Saúde do Amazonas, na figura do Exmo Sr Secretário de

Saúde Dr Wilson Duarte Alecrin por acreditar e apoiar o sonho de uma jovem médica.

A FAPEAM, PPSUS e a FMT-HVD por alocarem os recursos necessários à realização

deste estudo.

Ao Dr Joaquim Alves de Barros Neto por sua amizade e apoio fundamental a este

estudo.

Aos colegas do plantão de domingo do Hospital Dr João Lúcio Pereira Machado por seu

apoio, amizade e incentivo à concretização deste estudo.

Ao diretor do Hospital de Aeronáutica de Manaus, Cel Med Jorge Viana Annibal pelo

apoio e concessões indispensáveis à concretização deste projeto.

A coordenação e mestres do programa de Doutorado strictu sensu em Doenças

Tropicais e infecciosas da Universidade Estadual do Amazonas e Fundação de Medicina

Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado pela confiança, apoio e estímulo a conclusão deste

estudo.

A farmacêutica Andreza Fernandes pelo apoio e dedicação na execução dos

procedimentos imunohistoquímicos, tão necessários ao fortalecimento deste estudo.

Ao Farmacêitico João Paulo Pimentele e ao Enfermeiro Allyson Guimarães pelo apoio,

esclarecimentos e auxílio indispensáveis a execução dos procedimentos de citometria de

fluxo.

v

A farmacêutica Carolina Marinho e a biomédica Renata Galvão pela presteza e esmero

na execução dos testes moleculares cumprindo meu exíguo prazo.

Aos alunos do projeto de pesquisa “Câncer Anal”, em especial a Aline Hada, Josy

Abranches, Isabella Aguiar e Bruno Queiroz pelas horas de dedicação a este trabalho,

por compartilharem a minha angústia e por me incentivarem a permanecer na pesquisa.

Aos amigos que souberam compreender minha ausência e esquecimentos, em especial

à Paula Hargraves e à Júnia Ferreira Dutra que nos momentos de angústia sempre me

ofereceram afeto.

Ao meu pai, Bento Daumas, in memoriam, pela herança do prazer pelo estudo e pelo

orgulho refletido em seu olhar.

A minha mãe, Sebastiana de Carvalho Gonçalves, por ser tão maravilhosa e por sua

docura, braveza e honestidade com os quais nos educou. Jamais conseguirei

compensar seus esforços!

A meus filhos Paulo, Roberta e Bárbara, meus verdadeiros tesouros, pelo seu amor, por

terem suportado minha ausência, e por permanecerem junto à mim.

Ao meu amado marido José Jorge Pinheiro Guimarães pelo exemplo, impulso à vida

acadêmica, questionamentos científicos certeiros e principalmente por seu grande e

maravilhoso coração.

A Deus por tanto ter me dado sem que houvesse merecimento algum. A Ti, meu Senhor

e Salvador toda Honra e Toda a Glória!

vii

RESUMO

INTRODUÇÃO: Em todo o mundo a infecção pelo vírus da imunodeficiência humana

(HIV) estendeu-se primariamente como resultado da exposição sexual ocasionando um

acentuado aumento da incidência global do câncer anal. Nestes indivíduos, as interaçoes

entre vírus como o HPV, Herpes simples, Citomegalovírus e Epstein-Barr são frequentes

na região perianal e parecem aumentar o risco de células infectadas pelo HPV causarem

lesões neoplásicas, decorrente da indução à respostas imunes tolerogênicas associadas

as falhas na resposta citotóxica. Apesar do advento da terapia antiretrovital (TARV) ter

sido essencial para a queda da morbidade e mortalidade associada a infecção pelo HIV,

a reconstrução imune celular apresenta falhas traduzidas pelo aumento dos tumores não

definidores de aids, entre eles o câncer anal. MATERIAIS E MÉTODOS: No primeiro

estudo as taxas de co-infecção anal em pacientes com NIA foram avaliadas em 69

pacientes HIV-positivos e 30 HIV-negativos do sexo masculino submetidos à avaliação

citológica por captura híbrida para a detecção do HPV e PCR em tempo real vírus para

detecção do Epstein-Barr (EBV), Citomegalovírus (CMV), Herpes (HSV) tipo 1 e 2,

anuscopia magnificada e análise histopatológica. No segundo estudo, uma abordagem

de biologia de sistemas foi utilizado, a fim de integrar diferentes parâmetros

imunológicos do tecido da mucosa anal e do sangue periférico avaliada por análise

fenotípica e intra-citoplasmática de linfócitos e subpopulações de células dendríticas. Os

pacientes foram submetidos à análise histopatológica, seguida de análise, por citometria

de fluxo, das células dendríticas (CD11c+/CD123-, CD11c-/CD123+, CD1a+ e CD209+),

de linfócitos (CD45+ e CD3+/CD4+) além da expressão de citocinas séricas e

citoplasmáticas. RESULTADOS: No primeiro estudo a taxa de coinfecção viral foi de

16,9% nos casos de DST e diretamente correlacionada à carga viral HIV-1 maior que

10,001 cópias / mL (p= 0,017). A prevalência de NIA foi de 35% e restrita aos pacientes

HIV positivos. Os pacientes infectados com o HPV de alto risco e com contagem inferior

a 50 células T CD4+/mL apresentaram taxa de neoplasia intraepitelial anal(NIA) de

85,7%, (p <0,01). No segundo estudo, avaliamos 60 pacientes HIV-positivos e 25 HIVnegativos (sem fatores de risco para o câncer anal). Os dados demonstram que as

células mononucleares da mucosa anal de pacientes HIV(+)NIA(+) mostraram uma

robusta capacidade de produção de citocinas pró-inflamatórias/reguladoras,

principalmente mucosa (m)TNF-α > IL-4> IL-10> IL-6 = IL-17a. TNF-αIFN-γ/IL-17a da

mucosa são biomarcadores seletivos da HSIL. Níveis circulantes elevados de células

CD11c+ CD123Low e CD1a+, juntamente com níveis elevados de células IFN-γ+ TCD4+

são características importantes associadas ao HSIL em pacientes (NIA+)(HIV+).

Independentemente da presença de NIA, pacientes HIV(+) apresentaram uma rede

complexa de biomarcadores, rico em conexões negativas. Entre esses pacientes, no

entanto, os pacientes HSIL+ exibiram vínculos positivos mais fortes entre o sangue

periférico e o ambiente da mucosa anal, exemplificadas pela sub-rede de IL-17a/TNFα/CD4+ IFN-γ+/ células CD11c+CD123Low.

CONCLUSÕES: Na principal Instituição para o tratamento de HIV/aids na região

amazônica do Brasil, a co-infecção anal pelo HPV, CMV, HSV-1, HSV-2 e EBV ocorreu

seletivamente em pacientes HIV-positivos sendo influenciada pela carga viral do HIV. A

associação significativa entre HSIL e os níveis de TNF-α / IL-17A / IFN-γ juntamente com

os diferentes subconjuntos de DC presentes no ambiente da mucosa anal deve ser

estudado em mais detalhe como uma maneira de identificar e categorizar os pacientes

HIV (+) sob alto risco de desenvolvimento do câncer anal.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Canal anal, Células dendríticas, Co-infecção anal, HIV, aids,

Papilomavírus Humano, HPV, PCR em tempo real, Análise Histopatológica, Epstein-Barr

Vírus, EBV, Citomegalovírus, CMV, Herpes Simples Vírus, HSV, Neoplasia intraepitelial

escamosa anal, NIA, Resposta imune, Citocinas, Citometria de fluxo.

vii

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Worldwide infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)spread

primarily as a result of sexual exposure causing a sharp increase in the overall incidence

of anal cancer. In these individuals, the interactions between viruses like HPV, herpes

simplex, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus are frequent in the perianal region and

appear to increase the risk of HPV-infected cells cause neoplastic lesions resulting from

the induction of tolerogenic immune responses associated with failures in the response

cytotoxic. Despite the advent of antiretrovital therapy (ART) have been essential to the fall

of the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection, the cellular immune

reconstruction has flaws translated by the increase in non-AIDS-defining tumors, including

anal cancer. In the studies we demonstrate rates of NIA and anal coinfection and that the

evaluation of systemic and compartmentalized anal mucosa immune response is relevant

to differentiating HIV(+) patients at risk of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN). MATERIALS

AND METHODS: In the first study, anal rates in co-infected patients with NIA were

evaluated in 69 HIV negative (-) and 30 HIV (+) male patients undergoing cytologic

evaluation by hybrid capture assay for HPV detection and real time PCR for detection by

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes (HSV) types 1 and 2, magnified

anuscopy and histopathological analysis. In the second study, a systems biology approach

was utilized in order to integrate different immunological parameters from anal mucosal

tissue and peripheral blood assessed by phenotypic and intra- cytoplasmic analysis of

lymphocytes and dendritic cell subsets. RESULTS: In the first study, the rate of viral

coinfection was 16.9% in cases of STD and directly HIV-1 viral load greater than 10,001

copies/mL correlated (p = 0.017). The anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) prevalence was

35% and restricted to HIV (+) patients. Patients infected with high-risk HPV and with less

than 50 TCD4+ cells/mL showed count rate of AIN of 85.7% (p <0.01). In the second

study, we evaluated 60 HIV (+) patients and 25 HIV negative (-) (no risk factors for anal

cancer). Our data demonstrated that anal mucosal mononuclear cells from

AIN(+)HIV(+)patients showed a robust capacity in producing proinflammatory/regulatory

cytokines, mainly (m)TNF-α > IL-4> IL-10> IL-6 = IL-17a. Mucosal TNF-α IFN-γ/IL-17a are

selective HSIL-related biomarkers. Higher levels of circulating CD11c+CD123Lowcells,

and CD1a+ cells along with elevated levels of IFN- γ+CD4+ T-cells are major features

associated with HSIL in AIN(+)HIV(+)patients. Regardless of the presence of AIN, HIV(+)

patients presented a complex biomarker network, rich in negative connections. Among

those patients, however, HSIL+ patients displayed stronger positive links between

peripheral blood and anal mucosa environments, exemplified by the subnet of IL-17A/TNFα /CD4+IFN- γ+/CD11c+CD123Low cells. CONCLUSIONS: In the main Institution for the

HIV/AIDS treatment of in the Amazon region of Brazil, the co-anal infection by HPV, CMV,

HSV-1, HSV-2 and EBV selectively occurred in HIV(+) patients with viral load HIV

associated. The significant association between HSIL and the levels of TNF-α/IL-17A/IFNγ along with the different subsets of DCs present in the anal mucosa milieu should be

studied in more detail as a way to identify and cathegorize HIV(+) patients vis à vis the

high risk of anal cancer outcome.

KEYWORDS: Anal cancer, dendritic cells, anal co-infection, HIV, aids, Human

Papillomavirus, HPV, Histopathological analysis, Real time-PCR, Epstein-Barr Vírus, EBV,

Herpes Simplex Virus, HSV, Anal Intraephitelial Neoplasia, AIN, Anal cancer, Immune

response, Cytokines, Flow cytometry.

viii

LISTA DE FIGURAS

Figura 1 - Anatomia do canal anal- Secção longitudinal ..............................................2

Figura 2 - Modelo de Diferenciação das DC.................................................................11

Figura 3 - Interação entre DC imatura, contendo o vírus da imunodeficiência símia

e linfócitos t cd4+. ..........................................................................................................14

Figura 4 - Identificação dos Leucócitos (CD45+) no programa FlowJo (versão 9.4) 29

Figura 5 - Identificação dos Linfócitos T CD4+ no programa FlowJo (versão 9.4)...29

Figura 6 - Identificação das Células Dendríticas Epiteliais (CD1a+) no programa

FlowJo (versão 9.4) ........................................................................................................30

Figura 7 - Identificação das Células Dendríticas Subepiteliais DC-SIGN (CD209+) no

programa FlowJo (versão 9.4).......................................................................................30

Figura 8 - Identificação dos Linfócitos T CD4+no programa FlowJo (versão 9.4)....34

Figura 9 - Identificação dos Monócitos (CD14+)no programa FlowJo (versão 9.4)..35

Figura 10 - Identificação das Células Dendríticas CD1a+no programa FlowJo

(versão 9.4)......................................................................................................................35

Figura 11 - Identificação das Células Dendríticas Mielóides (CD11c+/CD123-)(A) e

Plasmocitóides (CD11c-/CD123+)(B) no programa FlowJo (versão 9.4) ....................36

ARTIGO 4.1

Figura 1 - Representative flow cytometric analysis of mononuclear cell

subsets…………………………………………………………………………………………..66

Figura 2 - Phenotypic and functional features of peripheral blood and anal mucosal

mononuclear cells from AIN(-)HIV(-) ( ),AIN(-)HIV(+) ( ) and AIN(+)HIV(+) ( )

individuals.......................................................................................................................67

Figure 3 - In vitro cytokine secretion profile (IL-6, TNF, IL-2, IFN-Y, IL-4, IL-10

AND IL-17A) of anal mucosa (M) and peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells from

AIN(-)HIV(-), AIN(-)HIV(+) and AIN(+)HIV(+) individuals……………………….………68

Figura 4 - Histopathology, phenotypic and functional features associated with anal

intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN).......................................................................................69

Figura 5 - Systemic analysis of phenotypic and functional features of peripheral

blood and anal mucosa of HIV(+) patients and

controls............................................................................................................................70

ARTIGO 4.2

Figura 1 - Rates of anal viral coinfection......................................................................83

ix

LISTA DE QUADROS E TABELAS

Quadro 1 - Classificação clínica e laboratorial dos pacientes com infecção pelo HIV

............................................................................................................................................7

Quadro 2 - Anticorpos utilizados para a marcação celular da mucosa anal ............28

Quadro 3 - Anticorpos utilizados na marcação das células mononucleares do

sangue periférico............................................................................................................33

ARTIGO 4.1

Tabela 1 - Description of the study population ..........................................................65

ARTIGO 4.2

Tabela 1 - The association of ain with oncogenic

HPV…………………………………80

Tabela 2 - The relationship between ain severity and the duration of HAART

use………………………………………………………………………………………………..82

Tabela 3 - The occurrence of ain in relation to the peripheral levels of t CD4 cells in

HIV-positive individuals infected with high-risk HPV..…………………………………83

Tabela 4 - Histopathological studies of coinfected patients………………………….84

xi

LISTA DE ABREVIATURAS E SÍMBOLOS

Aids

AMI

APC

AR

CBA

CDC

CD

CD1a

CD4+

CD8+

céls/mm2

CMV

CTL

CXCR4

CXCR7

DST

DC

DC-SIGN

DNA

EDTA

EFV

FACS

FCECON

FITC

FMT-HVD

Fms-like

FLT3

FSC

Síndrome da imunodeficiência adquirida

Anuscopia com magnificação de imagens

Células apresentadoras de antígenos

Adeptos do sexo anal receptivo

Cytometric bead array

Center of diseases control and prevention

Cluster of differentiation

Membro da família do grupo I das proteínas CD1. Glicoproteína

expressa na superfície de células apresentadoras de antígenos

Grupo especializado de linfócitos T que expressam o receptor CD4,

também chamado de linfócito T helper

Grupo especializado de linfócitos T que expressam o receptor CD8,

também chamado de linfócito T citotóxico

Células por milímetro ao quadrado

Citomegalovírus

Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte (linfócitos T citotóxico)

Receptor celular (de quimiocinas) tipo 4

Receptor celular (de quimiocinas) tipo 7

Doenças sexualmente transmissíveis

Células dendríticas

DC-specific, ICAM-3 grabbing, nonintegrin

Ácido desoxiribonucleico

ácido etilenodiamino tetraacético

Efavirenz

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter

Fundação Centro de Controle de Oncologia do Estado do Amazonas

isotiocianato de fluoresceína

Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr Heitor Vieira Dourado

Soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1

fms-like tiyrosine kinase 3 ligant

Forward Light Scatter

xii

GM-CSF

HAART

HEMOAM

HIV

HPV

HSH

HSIL

HSV

IC

ICAM

IL

iNOs

IFN

INCA

INTR

INTR

LC

LPG

LPV/r

LSIL

M-CSF

MDDC

MDSC

MSC

MFI

MFF

MHC

Nef

NIA

NIA I

NIA II

NIA III

NIC

NK

NIC I

NIC II

NIC III

OR

PMA

PBS

PBMC

PCR

PE

PERCP

RNA

Fator estimulador de colônia de granulócitos e macrófagos

High activity antiretroviral therapy (terapia anti-retroviral de alta

potência)

Fundação de hematologia e hemoterapia do Amazonas

Human immunodeficiency vírus (vírus da imunodeficiência humana)

Human Papillomavírus (papilomavírus humano)

Homens que fazem sexo com homens

High Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (lesão intra-epitelial escamosa

de alto grau)

Herpes simples vírus

Intervalo de confiança

intercellular adhesion molecule (molécula de adesão intercelular)

Interleucinas

Oxido nítrico síntase

Interferon

Instituto de Oncologia

Inibidores nucleosídeos da transcriptase reversa

Inibidores não-nucleosídeos da transcriptase reversa

Langerhan’s cells (células de Langerhan’s)

Linfadenopatia generalizada persistente

Lopinavir/ritonavir

Low Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (lesão intraepitelial escamosa

de baixo grau)

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

Célula dendrítica derivada de monócitos

Células supressoras de linhagem mielóide

Myeloid suppressor cells (células mielóides supressoras)

média de intensidade de fluorescência

Macs Facs fix (Solução Fixadora)

Major Histocompatibility Complex (complexo principal de

histocompatibilidade)

Negative factor (fator negativo)

Neoplasia Intraepitelial anal

Neoplasia Intraepitelial anal de baixo grau ou leve

Neoplasia Intraepitelial anal de moderado grau

Neoplasia Intraepitelial anal de alto grau ou grave

Neoplasia Intraepitelial cervical

Natural Killer

Neoplasia Intraepitelial cervical de baixo grau

Neoplasia Intraepitelial cervical de moderado grau

Neoplasia Intraepitelial cervical de baixo grau

Odds ratio (razão de chances)

acetato miristato de forbol

Phosphate buffered saline

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (Células mononucleares do

sangue periférico)

Reação de cadeia da polimerase

phico eritrina

peridina-clorofila

Ácido ribonucléico

xiii

RLU

RNA

RPMI

RR

R5

SCC

STAT5

SIV

TA

TAM

TAP

TARV

TCLE

TDF

TGF-ß

TILs

TNF-α

TNF- ß

TLR

Treg

UFAM

UEA

VEGF

ZTA

3TC

WHIM

relative light units

Ácido ribonucleico

Roswell Park Memorial Institute médium

Risco relativo

Vírus tipo 1 do HIV que utiliza o receptor CCR5

Right Angle Scatter

signal transducer and activator of transcription 5

Simian immunodeficienty vírus (vírus da imunodeficiência dos símios)

Temperatura ambiente

Macrógagos associados a tumor

Transporter associated with antigen presentation

Terapia anti-retroviral de alta potência

Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido

Tenofovir

Fator de crescimento e transformação tumoral beta

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

Fator α de necrose tumoral

Fator ß de necrose tumoral

Receptores TOLL-like( receptores do tipo Toll)

Células T Regulatórias

Universidade Federal do Amazonas

Universidade Estadual do Amazonas

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Zona de transição anal

Lamivudina

Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Infections and Myelokathexis

syndrome

xiv

SUMÁRIO

1 INTRODUÇÃO................................................................................................................. 1

1.1 Aspectos Relevantes que Cercam a Anatomia do Canal Anal ..................................1

1.2 A Neoplasia Intraepitelial Cervical e Anal ..................................................................2

1.2.1 Incidência do Câncer Anal ....................................................................................3

1.2.2 Fatores de Risco Relacionados à Neoplasia Intraepitelial Anal ...........................4

1.3 O papel do Papilomavírus humano (HPV) .................................................................5

1.4 Incidência da aids e Epidemiologia do HIV na Neoplasia Intraepitelial Anal e no

Câncer ..............................................................................................................................6

1.5 Classificação Clínica e Laboratorial da Infecção pelo HIV-1......................................6

1.5.1 A Terapia Antirretroviral de Alta Potência (TARV) ................................................8

1.5.2 O papel da TARV na progressão da NIA/câncer ..................................................8

1.6 Resposta Imune e a Caracterização das Células Dendríticas ...................................9

1.6.1 Maturação das Células Dendríticas ....................................................................10

1.6.2 Origem e Diferenciação das DC .........................................................................10

1.6.2.1. Facilitação da Aquisição Sexual do HIV ......................................................13

1.6.2.2 Células Dendríticas não-LC, co-receptores e a Infecção pelo HIV ..............14

1.6.2.3 O papel da DC DC-SIGN+ nas Infecções Via DC .........................................14

1.6.3 Variações nas Frequências das DC e o Risco de Câncer ..................................15

1.6.4 A geração de respostas regulatórias ..................................................................16

1.6.5 DC e a importância dos Mecanismos de Tolerância ..........................................16

1.6.6 Estratégias de escape tumoral ...........................................................................18

2 OBJETIVOS................................................................................................................... 21

2.1 Geral.........................................................................................................................21

xv

2.2 Específicos ...............................................................................................................21

3 MATERIAIS E MÉTODOS ............................................................................................. 22

3.1 Modelo de Estudo ....................................................................................................22

3.2 Universo de Estudo ..................................................................................................22

3.2.1 População de Estudo ..........................................................................................22

3.2.2 Critérios de Inclusão ...........................................................................................22

3.2.3 Critérios de Exclusão (para ambos os grupos) ...................................................23

3.3. Classificação e definição dos Grupos de Estudo ....................................................23

3.4 Procedimentos .........................................................................................................24

3.4.1 Coleta..................................................................................................................24

3.4.2 Emprego dos meios diagnósticos .......................................................................24

3.4.2.1 Anuscopia com Magnificação de Imagens (AMI) e Obtenção das Amostras

Teciduais ..................................................................................................................24

3.4.2.2 Coleta de amostra sanguínea ......................................................................25

3.4.2.3 Diagnóstico Histológico ................................................................................26

3.4.2.4 Preparo dos Fragmentos de Mucosa Anal ...................................................26

3.4.2.5 Cultura in vitro das células isoladas da Mucosa Anal ..................................27

3.4.2.6 Imunofenotipagem das células obtidas dos Fragmentos de Mucosa Anal ..27

3.4.2.7 Isolamento das Células Mononucleares (PBMC) por Gradiente de Ficoll ...31

3.4.2.8 Cultura in vitro das Células do Sangue Periférico ........................................31

3.4.2.9 Imunofenotipagem das Células do Sangue Periférico e marcação das

citocinas citoplasmáticas ..........................................................................................32

3.4.2.10 Dosagem de Citocinas no Sobrenadante de Cultura dos Fragmentos de

Mucosa Anal (Cytometric Bead Array - CBA) ...........................................................36

3.4.3 Detecção do HPV por Captura Híbrida ...............................................................37

3.4.4 Diagnóstico Molecular dos vírus Herpes 1 e 2, EBV e CMV através do Rapid

Real-Time PCR System .................................................................................................38

3.4.5 Diagnóstico sorológico do HIV ............................................................................38

3.4.6 Contagem de linfócitos T CD4+ e determinação da carga viral do HIV ..............38

3.5 Análise dos Resultados ............................................................................................39

3.5.1 Amostra...............................................................................................................39

3.5.2 Cálculo da Amostra.............................................................................................39

3.5.3 Tratamento Estatístico ........................................................................................39

3.5.4 Considerações Éticas .........................................................................................40

4 RESULTADOS E DISCUSSÃO ..................................................................................... 40

xvi

4.1 Artigo 1. CD11c+CD123Low Dendritic Cell subset and the triad TNF-α/IL-17A/IFN-γ

integrate mucosal and peripheral cellular responses in HIV patients with High-grade

anal intraepithelial neoplasia – a systems biology approach. ........................................41

4.2 Artigo 2. Coinfection of Epstein-barr Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Simplex Virus,

Human Papillomavirus and Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia in HIV Patients in Amazon,

Brazil. .............................................................................................................................71

5 CONCLUSÕES.............................................................................................................. 85

6 REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS .............................................................................. 86

7 ANEXOS ........................................................................................................................ 97

7.1 Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido .........................................................97

7.2 Cronograma de Execução Física .............................................................................99

7. 3 Orçamento – PPSUS-FAPEAM ............................................................................100

7.4 Equipe Científica ....................................................................................................103

7.5 Aprovação do Comitê de Ética em Pesquisas (CEP) ............................................104

7.6 Certificado de edição na língua inglesa referente ao artigo 4.1.............................105

7.7 Artigo suplementar - IHQ CD1a e DCSIGN ...........................................................106

7.8 Outras produções científicas ocorridas durante o doutoramento...........................125

1

1 INTRODUÇÃO

Em todo o mundo, a infecção pelo vírus da imunodeficiência humana (HIV)

estendeu-se primariamente como resultado da exposição sexual através das superfícies

mucosas, o que ocasionou significante aumento da incidência global do câncer anal

principalmente entre homens HIV positivos que fazem sexo com homens (Levis, 2010). o

câncer anal, à semelhança com o câncer cervical, apresenta como estágio precedentes

a neoplasia escamosa intraepitelial (NIA) e a forte associação causal com o HPV

(MELBYE e SPROGEL, 1991; PALEFSKY et al., 1991; ZAKI et al., 1992).

A defesa do organismo contra invasores virais potenciais nas mucosas é realizada

principalmente pela imunidade inata, que entre seus agentes efetores destaca-se as

células dendríticas dispostas nos sítios de interação entre o indivíduo e o meio, que

capturam e carreiam partículas virais até as estações linfáticas dando início a resposta

imune. Nos pacientes imunocomprometidos são descritos alterações no perfil fenotípico

e funcional das células dendríticas que acarretariam uma deficiente resposta imune

frente à infecções facilitando o desenvolvimento de neoplasias malignas locais (TAY et

al., 1987; SOBHANI et al., 2004; NADAL et al., 2006; BURG et al., 2007).

1.1 Aspectos Relevantes que Cercam a Anatomia do Canal Anal

O canal anal é a porção terminal do aparelho digestivo que mede cerca de 2,5 cm

e inicia-se à altura da linha pectínea e termina no orifício anal ou ânus, sendo revestido

por pele completa que se abre na região perineal em forma de fenda longitudinal (DINIZ,

1999). O ânus é precedido, por um segmento revestido por pele modificada desprovida

de pêlos, o anoderma, até a linha pectínea (Figura 1). O epitélio de revestimento do

canal anal é do tipo estratificado escamoso abaixo da linha pectínea e colunar simples

acima desta. A região é envolta pela musculatura puborretal.

2

Figura 1 - Anatomia do canal anal- Secção longitudinal

Fonte: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/489483_2

1.2 A Neoplasia Intraepitelial Cervical e Anal

O epitélio displásico ou portador de lesões intraepiteliais escamosas é

caracterizado pela presença de graus progressivos de anomalias de diferenciação

celular e de maturação, ocorridas desde a membrana basal até a superfície epitelial. As

alterações são classificadas em leve ou neoplasias intraepitelial escamosa de baixo grau

(NIAI), cujas alterações ocupam 1/3 da espessura do epitélio escamoso, podendo

apresentar células atípicas, porém sem mitoses atípicas. O grau moderado ou neoplasia

intraepitelial escamosa de grau moderado (NIAII), apresenta alterações que ocupam 1/2

da espessura do epitélio, onde células atípicas podem ser vistas, mas não figuras de

mitoses. Na forma grave ou neoplasia intraepitelial escamosa de alto grau (NIAIII) há

extensa destruição da arquitetura de todo epitélio, presença de atipias citoplasmáticas,

nucleares e mitoses. Por fim, a NIA pode evoluir para o carcinoma in situ ou o carcinoma

invasivo escamoso quando ocorre infiltração da lâmina própria por aglomerados de

células tumorais (BANDEIRA et al., 2001; APGAR e ZOSCHNICK, 2003; ABRAMOWIT

et al., 2007).

A neoplasia intraepitelial já é bem estabelecida como precursora do câncer cervical e

parece desempenhar papel semelhante na gênese do câncer anal. Sendo assim, a

3

transposição do conhecimento da oncogênese do câncer cervical para o câncer escamoso

anal foi apresentada por compartilharem características biológicas, inclusive sob aspectos

histopatológicos e anatômicos, como a zona de transição epitelial, o papel do HPV e

similaridades entre a lesão intraepitelial escamosa cervical e a anal, consideradas precursoras

dos cânceres cervicais e anais, respectivamente (MELBYE e SPROGEL, 1991; PALEFSKY

et al., 1991; ZAKI et al., 1992)

Chin-Hong et al. (2005) postulam que a evolução para o desfecho do carcinoma

anal ocorra entre 9 a 10 anos. Apesar da progressão da NIA de neoplasia intraepitelial

anal leve (NIA I) a NIA III nem sempre ocorrer, ela é clinicamente importante, conforme

relatado por Palefsky J. (2000), quando reporta 62% de NIA I em pacientes portadores

do vírus da imunodeficiência humana e em 36% de homossexuais masculinos HIV

negativos, com progressão da lesão para NIA III em 2 anos

1.2.1 Incidência do Câncer Anal

O câncer anal é incomum na população geral, com uma incidência de 0,8 casos

para cada 100.000 habitantes, sendo até cinco vezes mais incidente em mulheres e,

após a sexta década de vida (FRIEDMAN et al., 1998; LOIOLA, 2007). Após a epidemia

de aids, a prevalência do câncer anal entre homens que fazem sexo com homens (HSH)

tornou-se superior a do câncer cervical, antes do emprego da técnica do Papanicolau

para o seu rastreamento (PALEFSKY e HOLLY, 1995), sendo impulsionada a

35/100.000 em HSH HIV negativos a até 80/100.000 em HSH HIV positivos com baixos

níveis periféricos de linfócitos T CD4+ (MARTINS, 2005; VOLBERDING, 2000),

passando, nestes grupos, a ser mais prevalente na terceira e quarta décadas de vida

(FRIEDMAN et al., 1998)

No Brasil, o Instituto Nacional do câncer (INCA) publicou que no período de 2000

a 2004, foram registrados 234 casos de câncer anal na cidade de São Paulo, enquanto

no mesmo período apenas 10 casos foram registrados no Amazonas (INCA, 2010). Na

revisão realizada no banco de dados da Fundação Centro de Controle de Oncologia do

Estado do Amazonas (FCECON), principal Instituição pública de referência no

tratamento de neoplasias malignas do Estado do Amazonas, no período de 2002 a

outubro de 2011, foram registrados 42 casos de carcinoma do ânus, 12 em homens, dois

4

destes em pacientes HIV-positivos (FCECON, 2011). Na

Fundação de Medicina

Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado (FMT-HVD), principal unidade de referência para o

tratamento do HIV/aids no Estado do Amazonas, em quase sete anos de rastreamento

do câncer anal, somente 01 caso de carcinoma epidermóide anal foi detectado em

paciente HIV-positivo, do sexo feminino e que apresentava histórico de radioterapia por

carcinoma de colo uterino. (DAUMAS et al., 2011- dados referentes aos anos de 2005 e

2006; GIMENEZ et al., 2008; TRAMUJAS et al., 2011)

1.2.2 Fatores de Risco Relacionados à Neoplasia Intraepitelial Anal

Vários eventos têm sido imputados no desfecho NIA/câncer, com importâncias

díspares entre os estudos, em especial os relacionados aos fatores sóciocomportamentais, dentre eles a multiplicidade de parceiros sexuais, o tabagismo, as

doenças sexualmente transmissíveis (DST) e a prática do sexo anal receptivo (AR)

(DALING et al.,1987; KREUTER et al., 2005). Fatores biológicos como a presença de

NIA, a frequência das células dendríticas na mucosa e a imunodepressão sistêmica são

também apontados como contribuintes à este desfecho (SOBHANI et al., 2002,

YAGHOOBI et al., 2010)

Entre homossexuais HIV negativos, adeptos da prática do sexo anal receptivo,

Chin-Hong et al. (2005) descreveram importantes taxas de NIA, 15% de NIA I e 5% de

NIA III e taxas de detecção do HPV entre 20% e 57% respectivamente. O risco de

desenvolvimento do câncer quando relacionado com AR tem apresentado conflitos entre

os dados dos autores, não se mostrando como fator de risco isolado para Sobhani et al.

(2001; 2004), embora os estudos de Daling et al. (1987) tenham relatado NIA III em

37% dos HSH homossexuais ou bissexuais e em apenas 1 caso no grupo controle,

representando risco de 33,1 para o grupo masculino e de 1,8 para o feminino

Quanto a progressão da NIA, Palefsky et al. (1997) relataram estimativa da

progressão à NIA III de 49% em 04 anos entre os HSH HIV positivos e de 17% nos

demais, e segundo Palefsky et al. (2002), a taxa de NIA III, mesmo com o descontinuar

do sexo anal receptivo, tende a se manter

O papel das doenças sexualmente transmissíveis foi elegantemente abordado por

5

Daling et al. (1987) que descreveram risco de 17,2% para pacientes com histórico de

infecção pela Neisseria gonorrhoeae e de 2,3% para Chlamydia trachomatis e Herpes

simples virus tipo 2 (HSV-2)

em mulheres sem história de verrugas genitais. Em

indivíduos heterossexuais com verrugas genitais, o RR de câncer anal foi de 32,5

(DALING et al., 1987), sendo também elevado entre pacientes HIV positivos

heterossexuais (PIKETTY et al., 2003; WILKIN et al., 2004)

Estudos abordando a relação entre HPV - NIA - câncer, têm recebido ênfase nas

últimas décadas alavancado pelo aumento epidêmico das lesões intraepiteliais nos pacientes

coinfectados com o HIV. Em 1987, Pfister imputou ao HPV o papel de principal agente

iniciador da lesão intraepitelial cervical (NIC) e do carcinoma escamoso cervical (apud

PALEFSKY et al., 1991), sendo mais recentemente implicado na maioria dos tumores do trato

anogenital, com prevalências díspares (STEENBERGEN et al., 2005). Roka et al. (2008),

utilizando a captura híbrida encontraram o DNA do HPV de baixo potencial oncogênico

em 58,6%, e de alto risco em 51,4% de 555 amostras anais de HSH, independente do

status do HIV

1.3 O papel do Papilomavírus humano (HPV)

Os HPVs são vírus essencialmente epiteliotrópicos que necessitam romper a

barreira epitelial para invadirem as células da camada basal. Eles não são líticos e,

portanto não se liberam da célula até sua chegada à superfície epitelial (MARCHETTI et

al., 2002). Mais de 40 tipos de HPV foram descritos como capazes de infectar o trato

anogenital humano de ambos os sexos. A classificação do risco oncogênico é baseada

na freqüência de associação dos tipos com as neoplasias epiteliais de alto grau e o

carcinoma cervical (MUNOZ et al., 2003). Na população saudável, em mais de 80% dos

casos a evolução é frustra, com regressão às características epiteliais normais em torno

da décima sexta semana após a infecção, quando se observa a infiltração da mucosa

por linfócitos T citotóxicos (PALEFSKY e HOLLY, 2003; STEENBERGER et al., 2005)

Segundo Daling et al. (2004), o HPV é fator determinante na oncogênese do

câncer anal. A interação direta HPV-HIV tem sido demonstrada mesmo em pacientes

sem alterações nos níveis de linfócitos T CD4+, onde partes do genoma do HIV, como a

proteína tat, potencializariam a expressão de E6 e E7 do HPV (VERNON et al., 1993).

6

Para Palefsky (1997), a presença do HPV, o número de tipos detectados e a

quantidade de DNA são inversamente proporcionais aos níveis periféricos de células T

CD4+, tornando os pacientes mais propensos a desenvolverem NIA III, sugerindo que a

imunossupressão influenciaria a patogênese viral. Welters et al. (2006), demonstraram

resposta T específica contra HPV 18 satisfatória apenas em doadores saudáveis, o que

sugere falha na resposta T imune específica nos pacientes co-infectados com o HIV

1.4 Incidência da aids e Epidemiologia do HIV na Neoplasia Intraepitelial Anal e no

Câncer

A exposição sexual através das superfícies mucosas, foi em todo mundo,

imputada como o fator inicial relacionado a difusão da infecção pelo vírus HIV

(JAMESON et al., 2002). No Brasil até o ano de 2009 foram registrados 492.581 casos

de aids. No Amazonas, 5.341 casos foram notificados e cerca de 40% destes pacientes

declararam-se homossexuais ou bissexuais (BRASIL, 2010), a grande maioria destes

pacientes encontram-se em acompanhamento na FMT-HVD, principal Instituição de

referência no Estado.

Em pessoas infectadas pelo HIV o câncer é uma significante causa de mortalidade.

Segundo Spamo et al. (2002) apud Fernandez (2003), 30% a 40% desses pacientes irão

desenvolver alguma doença maligna durante a vida. O câncer anal é descrito nesta população

como “malignidade associada a aids” ou “câncer oportunista” (MELBYE et al., 1994;

FERNANDEZ, 2003), ocorrendo cerca de duas décadas mais precoce em relação ao grupo

controle (NADAL et al., 2006, YAGHOOBI et al., 2010). Na análise de 11 Estados americanos, o

risco do câncer anal em pacientes HIV positivos, foi de 6,8 nas mulheres e de 37,9 entre os

homens, elevando-se para 134 e 162,7 respectivamente, quando se avalia apenas indivíduos

com menos de 30 anos (KLENCKE e PALEFSKY, 2003). Sobhani et al., (2004), apontaram a

carga viral como ferramenta de valor na seleção dos pacientes com risco elevado para o

desenvolvimento da NIA.

1.5 Classificação Clínica e Laboratorial da Infecção pelo HIV-1

Pacientes infectados pelo HIV são classificados pelos níveis plasmáticos de

linfócitos T CD4+ e pela ocorrência das doenças definidoras de aids, conforme mostrado

7

no Quadro 1

Quadro 1 - Classificação clínica e laboratorial dos pacientes com infecção pelo HIV

Células CD4/mm3

Assintomáticos ou

Sintomáticos

Doenças

Infecção aguda

exceto A e C

indicadoras de aids

LPG

(1997)

> 500 mm3

A1

B1

C1

201 a 499 mm3

A2

B2

C2

< 200 mm3

A3

B3

C3

Fonte: World Health Organization (WHO-CDC) (2005)

Uma vez classificado como A3, B3, C1, C2 e C3 os pacientes devem ser

notificados como aids, não podendo, o paciente, ser reclassificado quando cessarem os

sintomas. Segundo Bazin (2005) são considerados portadores de aids os pacientes que

apresentam as doenças definidoras da doença com quaisquer níveis de T CD4+ ou os

com contagem de linfócitos T CD4+ inferior a 200/mm³, mesmo sem relato de infecção

oportunista.

Apesar do conhecimento prévio sobre a importância da queda dos linfócitos T

CD4, existe, segundo a convenção de Amsterdam (2010), evidências de que altos níveis

de ativação imune seriam prejudiciais aos pacientes HIV-positivos. Hazenberg et al

(2003), descreveram numa coorte prospectiva, que niveis elevados de células TC4+,

TCD8+, de ativação de células T ou de divisão celular como preditores independentes

da progressão da aids. O estudo afirma também que um sistema imune ativado antes da

infecção pelo HIV, como nos pacientes com DST anais por exemplo, onde há erosão das

células T ocasionada pela contínua ativação do sistema imune, ou quando ocorre rápida

depleção das células T após a soroconversão apresentariam maior risco de

desenvolvimento da aids.

Em outro estudo, realizado com pacientes infectados

assintomáticos por longos períodos, revelou que estes pacientes abrigavam vírus de

igual virulência mas que suas células T apresentavam baixas taxas de ativação

(CHOUDHARY et al., 2007).

8

1.5.1 A Terapia Antirretroviral de Alta Potência (TARV)

A ampliação do acesso da população aos esquemas TARV foram responsáveis

pela queda da morbimortalidade associada a aids na maioria dos países (FERNANDEZ,

2003). Os antirretrovirais são classificados em três grupos e a terapia inicial utiliza

frequentemente dois inibidores nucleosídeos da transcriptase reversa (INTR) associados

a uma droga dentre as duas classes restantes (RAMOS FILHO, 2005). A terapia deve

ser iniciada antes do aparecimento de sintomas e de quedas pronunciadas nos linfócitos

T CD4+. Dados do encontro de Amsterdam em 2010, reafirmam que o início precoce da

TARV têm sido correlacionado a doença de progressão mais lenta e com menos falhas

terapêuticas.

Vários países relatam a elevação do número de casos de NIA após o início da

TARV. Segundo estudo de Critchlow et al., (1995), a incidência de câncer anal na era

pré-TARV era de 35 x 105 casos, passando a 92 x 105 na era pós-TARV e a não

regressão de neoplasias intraepiteliais de médio e alto grau em 75% destes pacientes.

1.5.2 O papel da TARV na progressão da NIA/câncer

A progressão de NIA grave ao câncer parece ocorrer em torno de uma década

(STEENBERGEN et al., 2005), sendo impulsionado pela incompleta restauração imune

proporcionada pela TARV, a prolongada exposição aos vírus oncogênicos e a

instabilidade genômica que podem resultar em prejudicada vigilância imune e

subseqüente elevação da incidência de tumores (FERNANDEZ, 2003).

Segundo Doorbar (2005), apesar da imunossupressão aumentar o risco de

desenvolvimento da NIA III, uma vez estabelecida a NIA, fatores genéticos como os

induzidos pelas oncoproteínas E6 e E7 do HPV parecem desempenhar um papel mais

direto na progressão da NIA ao câncer (DOORBAR, 2005), e uma vez instaladas as

mutações, a reconstrução do sistema imune pela TARV não se acompanha da

reconstrução da resposta imune específica ao HPV, como ocorre com outros patógenos

(PALLEFSKY e HOLLY, 2003).

Retamozo-Palacios (2004) e Abramowitz et al., (2007) concluíram que a melhora

9

da imunidade associada à era TARV não é capaz de prevenir a recorrência das lesões

relacionadas ao HPV. Porém, estudos recentes relatam taxas similares de sobrevida

entre pacientes HIV positivos e negativos acometidos pelo câncer anal (ABRAMOWITZ

et al., 2009), onde a restauração das funções imunológicas promovidas pela TARV,

como a redução de citocinas pró-inflamatórias associadas ao HIV (BARRETTA et al.

(2003), permitiria uma resposta imune satisfatória e tolerância a quimioterapia

(ABRAMOWITZ et al., 2009). A mudança do prognóstico destes pacientes em relação a

algumas doenças associadas ao HIV também foram descritas por Hessol et al. (2007).

Apesar do possível aumento da incidência da NIA ter uma parcela apoiada na

maior acessibilidade aos testes diagnósticos, o crescimento da patologia é alarmante e

vem encorajando a implementação de programas de rastreamento precoce das lesões

precursoras do câncer anal (PALEFSKY et al., 1998), principalmente em indivíduos

transplantados renais, HIV positivos e portadores de defeitos genéticos que acometam o

sistema

imune,

que

também

apresentem

particular

susceptibilidade

para

o

desenvolvimento de quadros infecciosos difusos e refratários (DOORBAR, 2005).

1.6 Resposta Imune e a Caracterização das Células Dendríticas

As células apresentadoras de antígenos (APC) são representadas por linfócitos,

células de Langerhan’s (células dendríticas imaturas) (LC), células dendríticas da

epiderme, macrófagos e linfócitos epiteliais disponibilizados nas camadas do epitélio,

sendo seu papel parte fundamental da resposta imune. As células dendríticas capturam

antígenos, processam-os e os expressam, em sua superfície, através do complexo

principal de histocompatibilidade (Major Histocompatibility Complex - MHC) de classe II,

e os apresentam aos linfócitos auxiliares T CD4+, desencadeando a resposta imune.

As formas imaturas das DC são levadas pela corrente sangüínea aos órgãos

periféricos como pele e mucosas, onde se instalam. As DC da pele ou LC possuem

grande poder migratório através dos plexos subepidérmicos, localizando-se nos sítios de

interação entre o indivíduo e o meio externo, onde formam extensa rede unidirecional

ascendente até os órgãos linfóides secundários iniciando, juntamente com linfócitos

intraepiteliais, a resposta imune contra antígenos inalados, ingeridos ou inoculados

(ABBAS e LICHTMAN, 2005c; PACHIADAKIS et al., 2005; ABBAS e LICHTMAN, 2005d;

10

JAMESON et al., 2002).

1.6.1 Maturação das Células Dendríticas

As DC antes de capturarem e fagocitarem os antígenos por macropinocitose ou

endocitose, são consideradas imaturas por expressarem pouco MHC, moléculas coestimuladoras e devido a expressão elevada de CD1a e receptores de quimiocinas como

os CCR1, CCR2, CCR5 e CCR6 que recrutam outras DC para os tecidos inflamados

(ZIMMER et al., 2002).

Durante o processo migratório, a expressão de MHC I, MHC II, como o HLA-DR,

moléculas co-estimuladoras, CD80 (B7-1) e CD86 (B7-2) e CD4 aumentam nas DC,

enquanto diminui a ligação e o processamento de novos Ag. exógenos, sendo então

consideradas DC maduras, que expressam ainda CXCR4 e CCR7 que direcionam a

migração celular até as áreas T dos tecidos linfáticos, auxiliadas pelas quimiocinas

linfonodais CCL19 e CCL21 (ZIMMER et al., 2002; KAWAMURA et al., 2005).

Na zona de células T, as DC maduras, têm a expressão de CD1a reduzida,

apresentam os antígenos capturados ( ZIMMER et al., 2002; KAWAMURA et al., 2005)

às células T que em resposta às citocinas e moléculas co-estimuladoras expressas

ativam macrófagos, fundamentais à resposta infecciosa aguda, que sofrem expansão

clonal e então migram para a pele para participarem da resposta inflamatória (ABBAS e

LICHTMAN, 2005c).

1.6.2 Origem e Diferenciação das DC

As DC são um grupo de APC bastante heterogêneas. Quanto à origem, as DC

apresentam precursores mielóides e linfóides; que, conforme a exposição e expressão

de receptores de citocinas, irão se diferenciar em DC mielóides, LC e DC

plasmocitóides, classificadas de acordo com seu fenótipo e morfologia. Os eventos são

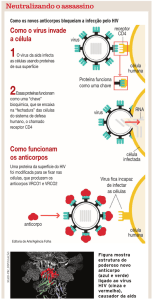

sumarizados na figura 2 (ARDAVÍN et al., 2001; WU e KEWALRAMANI, 2006).

11

Figura 2 - Modelo de Diferenciação das DC

Via comum de diferenciação das DC. Após as setas estão representados os produtos

finais de cada via de diferenciação. As principais citocinas envolvidas estão indicadas.

Legenda: FLT3: fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligant; IL: interleucina; TGF-ß: fator ß de

crescimento e transformação; TNF-α: fator α de necrose tumoral. Fonte: Ardavín et al.

(2001).

As DC mielóides(CD11c+/CD123-) são APC clássicas, pois apresentam os

produtos antigênicos degradados aos linfócitos T CD4+ e TCD8+, secretam citocinas próinflamatórias como a IL-12, essenciais ao desenvolvimento da resposta imune efetiva,

além de interferon I, quando infectadas por vírus, porém em menor quantidade que as

DC plamocitóides(CD11c-/CD123+) consideradas produtoras naturais de interferon,

porém com capacidade 10 a 50 vezes inferior para expandir células T CD4+ e TCD8+

(PACHIADAKIS et al., 2005; WU e KEWALRAMANI, 2006)

A secreção de citocinas pelas DC guiam as propriedades efetoras dos linfócitos T

naive (Reis e Sousa, 2006), onde a secreção de IL-12 parece induzir fortes respostas

efetoras nas células T, já a IL-10 parece induzir as células T a produzirem mais IL-10

com propriedades supressoras (SVENSSON et al., 2004). Numa abordagem simplificada

a

relação

entre

essas

citocinas

parece

definir

a

resposta

imune

como

predominantemente pró-inflamatória ou anti-inflamatória, o que também é influenciado

pela quantidade de antígenos e ligantes dos receptores do tipo toll nos patógenos

12

(PACHIADAKIS et al., 2005).

Turville et al., 2003 e Geijtenbeek et. al. (2000) descreveram, in vitro, as seguintes

subpopulações de DC no epitélio:

Ø LC intraepiteliais langerina+ CD1a+

Ø DC da derme, submucosas ou subepiteliais CD1a- CD14+ DC-SIGN+ (DCspecific, ICAM-3 grabbing, nonintegrin)

Ø DC da derme, submucosas ou subepiteliais CD1a+ CD14- DC-SIGNØ Células dendríticas derivadas de monócitos (MDDC) CD1a+ CD14+ DC-SIGN+

No sangue periférico Ito et al.(1999) descreveram 03 populações distintas de DC,

caracterizadas inicialmente pela expressão de CD1a e CD11c. As células eram

CD1a+/CD11c+/Lin-/DR+,

CD1a-/CD11c+/Lin-/DR+

e

CD1a-/CD11c-+/Lin-/DR+,

segundo os autores, a primeira e última populações eram as mais prevalentes

perfazendo aproximadamente 0,50 a 0,18% das PBMC de 30 voluntários saudáveis.

Com base na expressão de CD2, CD9, CD11b, CD11c, CD13, CD32, CD33,

CD64, e GM-CSFR, a população de células CD1a+/CD11c+, denominada fração 1, foi

definida como proveniente de linhagem de monócitos, derivadas do progenitor CD34,

não LC. Já a população de DC CD1a-/CD11c-, fração 3, expressavam pobremente

CD33, CD13, CD1c, CD2, CD49e, CD45RO, CD32, CD64, mas apresentavam

significativa expressão de CD45RA, possuindo portanto morfologia e fenótipo

compatíveis com DC plasmocitóides. Por fim, as DC CD1a-/CD11c+ ou fração 2, não

apresentam expressão de CD1a, CD1c, CD11b ou de CD64, mas expressam CD11c,

CD33, CD13 e GM-CSFR, indicando também serem da linhagem dos monócitos (CAUX

et al., 1997).

A capacidade de estimular células T e de endocitose de partículas de FITcdextran foram superiores nas frações 1 e 2, e após sete dias de cultura, apenas a cultura

da fração 1 das DC e em presença de GM-CSF, IL-4 e TGF- β1, foi capaz de diferenciar

DC à LC, confirmadas pela expressão de Langerin, CD1a e presença dos grânulos de

Birbeck (ITO et al., 1999).

13

1.6.2.1. Facilitação da Aquisição Sexual do HIV

Yaghoobi et al. (2010) descreveram a coinfecção HPV-HIV como fator de risco

para o câncer anal. Segundo Sheth et al., (2005) e Grosskurth et. al.,1995), a presença

de uma DST favorece a aquisição do HIV, por alterações induzidas no sistema imune

local, o que segundo Coen et al (1998) e Kaul et al. (2008) seria fator determinante local

para a aquisição da infecção. Na mucosa LC e queratinócitos respondem a infecção

induzindo o afluxo de monócitos, macrófagos, e células T CD4, além do aumento de

células NK, mediado pelas IL-12, IL-1 e IL-6 e DC plasmocitóides que secretam mais

IFN-α culminando, na maioria dos eventos, com o clareamento viral (DIVITO et al.,

2006).

Segundo Bosnjak et al.( 2005), os vírus como o HSV podem desencadear a

apoptose em LC, monócitos e células T, e Anzala et al. (2000), descreveram elevação

em até 10x nos níveis de IL-4, IL-6 e IL-10 e de HIV no sêmen de pacientes com

gonorréia, o que de acordo com Sheth et al (2006), independem da carga viral do HIV e

dos níveis periféricos das células T CD4.

Sprecher e colaboradores em 1986 demonstraram que a depleção de LC da

mucosa estaria associada ao aumento da virulência do HSV, e Jones et al (2003),

relataram o efeito deletério do HSV sobre as DC ocasionando a diminuição da produção

de IL-12. As alterações se estendem à resposta imune adaptativa pois de acordo com

Sheth et al. (2005) as células TCD8+ de pacientes infectados pelo HIV, apresentam

aumento das citocinas pró-inflamatórias no sêmem e na cérvix uterina.

Frank et al. (2008), enfatizaram a necessidade de pesquisas contínuas

objetivando as estratégias múltiplas para impedir a interação vírus-célula e a

amplificação viral nas DC. Neste sentido, duas moléculas capazes de vincular-se as

DC-SIGN (DC-specific, ICAM-3 grabbing, nonintegrin), a BSSL (sais biliares lipase

estimulada) encontrada no intestino e no leite humano e a MUC 6 no sêmen foram

descritas como capazes de bloquear a transferência do HIV às células T CD4, via DC e

devem alavancar estudos futuros (AMSTERDAN, 2010).

14

1.6.2.2 Células Dendríticas não-LC, co-receptores e a Infecção pelo HIV

Segundo Kawamura et al. (2005), o caminho a ser seguido pela infecção parece

depender do tipo celular encontrado inicialmente pelo HIV ao invadir o organismo e de

acordo com Hu et al. (2000) toda a subpopulação de DC são capazes de transportar o

HIV até o linfonodo.

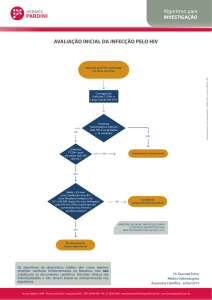

Na figura 3 observa-se, à microscopia eletrônica, a interação entre a DC madura,

o vírus da imunodeficiência símia, semelhante ao HIV, e as células T CD4+.

A

B

Figura 3 - Interação entre DC imatura, contendo o vírus da imunodeficiência símia

e linfócitos t cd4+.

A: interação dc-célula t CD4+, b: vírus da imunodeficiência símia e linfócitos t CD4+.

Aumento de 60x à microscopia eletrônica. Os vírus intactos estão identificados pelo

símbolo estrela. Fonte: Frank et al. (2008).

Geijtenbeek et al., 2000 relataram a capacidade do HIV em subverter a função

habitual das DC DC-SIGN+, ocasionando a transmissão viral às células T, via exossomo,

o que pode ter impacto no controle da infecção, considerando-se a produção artificial de

exossomos, visando o estímulo da resposta imune contra agentes infecciosos e tumorais

(SEGURA et al., 2005).

1.6.2.3 O papel da DC DC-SIGN+ nas Infecções Via DC

A ICAM-3 (intercellular adhesion molecule) é uma molécula de adesão intercelular

que adere a não-integrinas, inicialmente designadas como específicas das DC imaturas

15

e denominadas DC-SIGN. As células DC-SIGN+ são dispostas na derme, placenta,

mucosas, tecidos linfóides e de forma difusa nas fibras de tecido conjuntivo fibroso, mas

não em LC (SOILLEUX, 2002). Com o uso de Anticorpos específicos, Geijtenbeek et al.

(2000) demonstraram que as células que expressam DC-SIGN, na mucosa do reto e

vagina, são distintas dos linfócitos T e B, macrófagos ou monócitos, mas compatíveis

com as DC.

As DC DC-SIGN+ formam uma banda estreita logo abaixo do lúmem epitelial,

separadas apenas por uma tênue camada única de epitélio colunar, sendo o acesso viral

às estas células facilitado (JAMESON et al., 2002), ocasionando portanto, um maior

risco de transmissão do HIV-1 através do intercurso retal (VOELER, 1991; JAMESON et

al., 2002; KAWAMURA et al., 2005).

1.6.3 Variações nas Frequências das DC e o Risco de Câncer

A diminuição das DC tem sido relacionada a eventos como o agravamento da NIA

e o câncer anal (SOBHANI et al., 2002; NADAL et al., 2006, YAGHOOBI et al., 2010).

Para Arany et al. (1998) alguns tumores parecem secretar substâncias que incapacitam

as células dendríticas na promoção da imunidade antitumoral. Nos pacientes infectados

pelo HIV, o cenário é agravado pela diminuição do número total de células T CD4+ na

aids e pelo estado tolerogênico dos linfócitos associados à mucosa intestinal

(SCHIEFERDECKER et al., 1992).

Sobhani et al. (2004) encontraram uma média de 15 a 19 cél/mm2 em DC CD1a+

da camada basal anal na população geral, um aumento destas células, 24 a 27 cél/mm2,

em pacientes com condiloma anal e diminuição, 16 cél/mm2 à zero, nos pacientes com

NIA III ou câncer anal. Os achados foram corroborados por Nadal et al.( 2006) que

demonstraram uma diminuição de aproximadamente 50% na média das LC em

pacientes com câncer anal e de 50-75% nos pacientes HIV positivos com câncer anal.

Bella et al (2003) e Ferrari et al (2005) descreveram, em pacientes com câncer,

alteração nas populações de DC tipo-1 (mielóides) e tipo-2 (plasmocitóides) no sangue

periférico.

Quanto as DC plasmocitóides, sua resposta imune parece depender do tipo de

16

estímulo à ativação, do estágio de maturação e do tipo de antígeno (BOONSTRA et al.,

2003). Em relação a infecção pelo HIV, a frequência e a função das DC plasmocitóides

são inversamente proporcionais a carga viral do HIV (DONAGHI et al., 2001), e segundo

Levy et al. (2003), a TARV parece restaurar estas DC a níveis próximos a normalidade.

1.6.4 A geração de respostas regulatórias

Segundo Marguti, (2007) após o estímulo a maturação, as DC aumentam a

produção de citocinas pró-inflamatórias como a IL-12 e o TNF-α e mantêm os níveis de

TGF-ß e de citocinas supressoras, estando este evento relacionado à manutenção e

geração de células T regulatórias (Treg) Foxp3+.

Diferentemente de indivíduos saudáveis, onde as células T CD4+ específicas

produzem IFN-γ, em pacientes com câncer cervical associado a oncoproteína E6 do

HPV 16, a produção de IL-10 foi relacionada a geração de Linfócitos Treg específicos,

capazes de suprimir a produção de IFN-γ e IL-2 (BURG et al., 2007). Na mucosa anal,

foram descritos recentemente o aumento da IL-8 e IL-23 como associados a NIA III e o

câncer (YAGHOOBI et al., 2010).

Nos pacientes HIV-positivos, a infecção das DC prejudica o estímulo às células T

devido a perda da capacidade de maturação, consequente à deficiência de expressão de

moléculas co-estimuladoras e do MHC, ocasionando a inibição da secreção de citocinas

como a IL-12 e o retardo da resposta imune (PACHIADAKIS et al., 2005, LORÉ et al.,

2002), e associado a produção de citocinas regulatórias como a IL-10, induzidas por

células Treg.

1.6.5 DC e a importância dos Mecanismos de Tolerância

Na periferia, foi demonstrado que a manutenção da interação entre células Treg e

DC imaturas constituí importante mecanismo de manutenção da geração e expansão

das células reguladoras a partir dos linfócitos T naive, estando envolvida nos

mecanismos de tolerância e na manutenção da viabilidade de órgãos transplantados

(MIN et al., 2003) independente da IL-10 e do TGF-ß (CONG et al., 2005). Portanto, as

DC

estão

implicadas

nos

mecanismos

de

regulação

das

células

Treg

(CD4+CD25+highFoxp3+) por mecanismos de apoptose, anergia ou hiperexpressão de IL-

17

10 (MARGUTI, 2007).

De acordo com Burchill et al. (2007), a produção de células Treg é influenciada

pelos níveis de IL-15 e IL-2, onde cadeias ß do receptor ativariam o fator de transcrição

STAT-5 que se ligaria a regiões do Foxp3. A geração destas células depende também

da IL-10 produzidas pelas DC, porém a forma de ação das citocinas sobre a função

efetora das células Treg ainda não foi totalmente esclarecida (MARGUTI, 2007).

Gabrilovith et al., (2004) sumarizou as falhas na diferenciação de células

mielóides no câncer que acarretariam diminuição do número de DC mielóides no sangue

periférico e aumento proporcional do número de DC imaturas. Efeitos estes mediados

por fatores solúveis produzidos pelo tumor e reversíveis após a remoção da neoplasia e

quando colocadas em meio sem a presença de fatores tumorais (Gabrilovith et al.,

1997), como o VEGF, o Fator de Estimulação de Colônias de Granulócitos e monócitos

(GM-CSF) in vitro, Fator de Estimulação de Colônias de monócitos (M-CSF), Interferon-γ

(IFN-γ),

Fator

de

Crescimento

Transformador-β

(TGF-β),

Interleucina-6

(IL-6),

Interleucina-10 (IL-10) e gangliosideos (GABRILOVITH et al.,1999; MENETRIER-CAUX

et al., 2001; RATTA et al., 2002; BRONTE et al., 1999; STEINBRINK et al., 2002;

PEGUET-NAVARRO et al., 2003).

Diversos efeitos inibitórios imputados a IL-10, como a supressão de respostas T,

induzidas por DC tolerogênicas imaturas (SHARMA et al., 1999), a diminuição da

expressão de moléculas co-estimuladoras (STEINBRINK et al., 1999) e a supressão da

proliferação da resposta T CD4+ e TCD8+ ocorrem devido ao contato direto célula-célula

entre DC tratadas e células T naïve (STEINBRINK et al., 2002). Almand et.(2010) não

encontrou correlação entre IL-10 séricas e defeitos na diferenciação de DC em pacientes

com câncer, mas em ratos a diferenciação de DC pode ser alterada pela IL-10,

GABRILOVICH; 2004, SHARMA et al ,1999).

A importância do STAT3 foi demonstrada na diferenciação anormal de células

mielóides em pacientes infectados com HPV (NEFEDOVA et al., 2004; WANG et al.,

2004), já que o STAT3 é necessário na via usada pelas citocinas para diferenciar estas

células juntamente com a JAK2 (NEFEDOVA et al., 2004). A IL-10 é um reconhecido

ativador da atividade da STAT3, Gabrilovith et al., (2004) sintetizou as interações entre

IL-10, DC e STAT3, os autores associaram o aumento da STAT3, na presença de

18

fatores derivados do tumor, com o acúmulo de DC imaturas e diminuição da produção de

DC no sangue periférico.

A capacidade de células supressoras de linhagem mielóide (MDSC) em induzir a

formação de Treg foi descrita por Huang et al. (2006), na presença de células T tumorais

específicas ativadas, IFN-γ e IL-10 e independente dos níveis do óxido nítrico (NO)

observados no sobrenadante de cultivo de MSC e Linfócitos T CD4+ de esplenócitos de

ratos transgênicos.

Em sua revisão Gabrilovich e Nagaraj (2009) descreveram os indícios de que a

supressão tumoral ocorra de maneira distinta no sítio tumoral e na periferia, onde MDSC

chegariam ao sítio tumoral e aumentariam a expressão de arginase e induziriam o iNOs

(Oxido nítrico síntase) e a diminuição da expressão de reactive oxygen species (ROS) e

então as MDSC se diferenciariam em macrófagos associados a tumores (TAM)

(KUSMARTSEV E GABRILOVICH, 2005). O TAM produzem elevados níveis de citocinas

que suprimem a resposta nas células T, de forma não específica. O somatório dos

mecanismos antígeno específico, via STAT 3, e inespecífico via STAT1 e TAM

potencializariam os efeitos supressivos sobre os linfócitos T

Nas áreas de NIC, Kobayash et al. (2004), descreveram células CD1a+ produtoras

de IL-10 dispostas no estroma e não no epitélio, indicando a produção de células

regulatórias por células CD1a+, porém em quantidade menor nos pacientes HIV+NIC II/III

(15 cells/mm2) do que nos controles (23 cells/mm2) e nos HIV-CIN+ (69 cells/mm2). No

câncer de mama, Pinzon-Charry et al. (2005) descreveram apoptose de DC LIN-CD40- e

defeitos na maturação celular reversíveis na presença de CD40-L

1.6.6 Estratégias de escape tumoral

Vários são os mecanismos utilizados pelos tumores para forjarem sua presença e

evitarem seu reconhecimento e exterminação, um dos mais antigos é a produção direta

de IL-10 ou induzida por fatores solúveis tumorais. Como APC e macrófagos que podem

diminuir os níveis de MHC II, moléculas co-estimulatórias B7-1 e B7-2 e de citocinas

inflamatórias como IL-2 e IFN-γ (KELLY & BANCROFT, 1996; STEINBRINK et al., 1999)

19

e induzirem tolerância nas células Th1, T CD4+ (STEINBRINK et al., 1997) e TCD8+

(STEINBRINK et al., 1999) além de suprimirem células NK (KURTE et al., 2004).

O IFN-γ apesar de desempenha um papel fundamental na inclinação de células T

naive a um fenótipo Th1, através da inibição da produção de IL-4 (GAJEWSKI et al.,

1988) e indução da secreção de IL-12, pode ainda suprimir o desenvolvimento das

células Th17 a partir de células T naive em camundongos, mas também estimular

fortemente a expressão de IL-1 e IL-23 por APC mielóides levando a expansão de

memória de células Th17 em humanos (KRYCZEK et al., 2008).

O aumento da expressão da B7-H1 tem sido descrito em pacientes de alto risco

de progressão a leucemia aguda, onde o IFN-γ associado ao TNF-α induziria uma maior

expressão em blastos MDS (Kondo et al., 2010). O IFN-γ induz também o aumento da

IDO em DC e células Treg mediando a progressão ao câncer (MELLOR et al, 2008).

Macrófagos IFN+ foram associados à sobrevivência de células do melanoma (Garbe et

al., 1990). O IFN-γ também foi associado a apoptose de células T CD4+, afetando

indiretamente a função das células TCD8+ (Berner et al., 2007).

A apresentação de um efeito antagônico ao usual desempenhado por algumas

citocinas têm sido descrito na resposta tumoral. Wilke et al. (2011) e Yanagawa et al.

(2011) demonstraram que citocinas antagônicas podem trabalhar em sinergismo

suprimindo respostas imunoestimulatórias de DC através do aumento do óxido nítrico.

Outro mecanismo é o aumento da expressão da purified anti-indoleamine 2,3dioxygenase (IDO) nas APC, via IL-10, desencadeando mecanismos imunes regulatórios

(Yanagawa et al., 2008) que podem ser potencializados pelo aumento da IDO em DC e

células Treg, via IFN-γ, mediando assim a progressão ao câncer. Apesar dos efeitos

dúbios, Wilker et al., (2011) relataram que o efeito predominante da IL-10 e do IFN-γ

serão sempre regulatórios e inflamatórios respectivamente.

As citocinas não são as únicas a terem seus efeitos subvertidos. A função

reguladora das LCs tem sido discutida para diversas situações tolerogênicas

apresentadas (LUTZ, AZUKIZAWA, 2010). Segundo Stoitzner (2010), as LCs não são

obrigatórias para a indução de tolerância periférica contra autoantígenos expressos em

20

queratinócitos da epiderme. Assim, as LC podem exercer uma dupla função, ou seja,

induzirem a tolerância ou a imunidade, dependendo da situação específica na pele.

Além das Lc epiteliais, um subconjunto de DC dérmica Langerhan’s positivas

pode assumir o papel de induzir a tolerância periférica e a imunidade. Segundo Ueno et

al., (2010) as LCs parecem importantes para a indução de respostas às células T e DCs

dérmicas e seriam responsáveis pela indução a respostas humorais. Esse papel díspar

das DC tem promovido muita discussão científica como os estudos de Allan et al. ( 2003)

que demonstram que LCs não são necessárias às respostas das células T contra o vírus

herpes simplex que infecta células na epiderme. Burg et al. (2007), encontraram em

pacientes com câncer cervical associados ao HPV16, um aumento do IFN-γ e da citocina

supressora IL-10 como associadas a geração de células Treg.

Sendo o câncer anal uma das patologias de importância ascendente em

indivíduos HIV positivos, por não ser controlada pelo uso da TARV, elegemos esta área

para o estudo desta tese buscando aprofundar o conhecimento a cerca das alterações

imunes periféricas e locais associadas a NIA grave, lesão precursora do câncer anal,

com o intúito de acrescentar ferramentas objetivando manejo futuro do quadro

imunológico apresentado por estes pacientes, ainda na fase pré-neoplásica.

Para conhecer a relação da NIA grave com a produção e secreção de citocinas e

células dendríticas locais e periféricas e as interações virais em pacientes HIV positivos

delineamos este estudo, que analisou a variação na expressão de células dendríticas e

de citocinas na mucosa anal e sangue periférico de pacientes HIV positivos e doadores

sadios, correlacionando-os com a lesão intraepitelial anal e o câncer, em pacientes

atendidos na Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado, principal

instituição pública de apoio a pacientes HIV positivos de Manaus-AM.

21

2 OBJETIVOS

2.1 Geral

Analisar as taxas de coinfecção viral e os aspectos fenotípicos e funcionais da

resposta imune sistêmica e na mucosa anal de pacientes HIV positivos portadores de

neoplasia intraepitelial anal.

2.2 Específicos

1-Descrever as particularidades da resposta imune apresentada pelos pacientes nos

grupos estudados quanto ao status do HIV e a ocorrência de neoplasia intraepitelial anal;

2-Traçar correlações entre as alterações observadas no sangue periférico e na mucosa

anal;

3-Relacionar os tipos oncogênicos de HPV com o grau de neoplasia intraepitelial anal

entre os grupos HIV positivos e negativos;

4-Descrever as taxas de coinfecção anal entre os vírus HPV, CMV, EBV e HSV-1 e

HSV-2 e relacioná-las ao grau de neoplasia intraepitelial anal; e

5-Descrever a influência da carga viral do HIV e dos níveis periféricos de células T CD4+

nas taxas de coinfecção viral dos pacientes HIV-positivos.

22

3 MATERIAIS E MÉTODOS

3.1 Modelo de Estudo

Estudo observacional analítico prospectivo, transversal do tipo detecção de casos.

3.2 Universo de Estudo

3.2.1 População de Estudo

Foram estudados 85 pacientes do sexo masculino, 60 portadores de sorologia

positiva para o HIV e 25 pacientes controle (HIV negativos). A amostra foi composta por

pacientes encaminhados ao ambulatório de coloproctologia da FMT- HVD, provenientes

dos ambulatórios de DSTs/aids, dermatologia e ainda por pacientes HIV negativos que

procuraram a unidade por livre demanda, por apresentarem sintomas proctológicos.

Os indivíduos receberam informações por escrito sobre o conteúdo do estudo,

riscos e benefícios, sendo oferecido aos que se interessaram o termo de consentimento

livre e esclarecido (T.C.L.E.) (Anexo 7.1), para a coleta da assinatura, expressando o

livre interesse na participação deste estudo

3.2.2 Critérios de Inclusão

Grupo caso:

Pacientes do sexo masculino, HIV positivos, com idade compreendida entre 14

anos completos a 70 anos incompletos (com consentimento dos pais ou responsável

quando menores de 18 anos), divididos em grupos quanto à presença ou a ausência das

seguintes características: aids, ocorrência de NIA/câncer anal e se adeptos à prática do

sexo anal receptivo (AR), caracterizado pela prática do ato superior a 1X ao mês por

pelo menos 04 meses no ano.

23