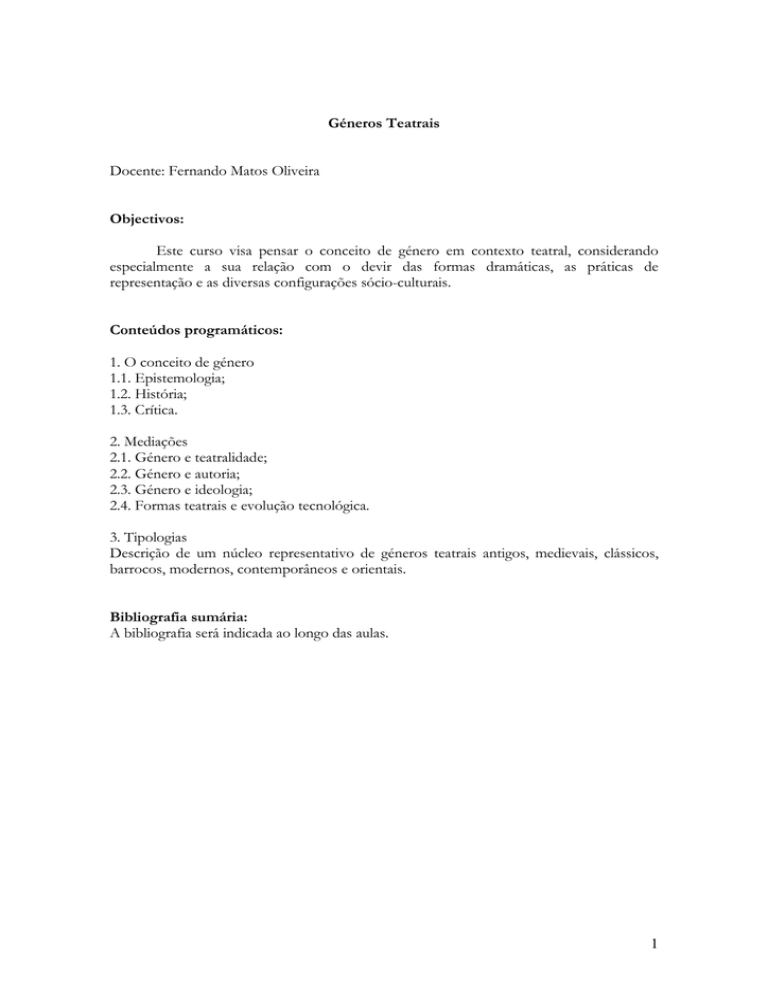

Géneros Teatrais

Docente: Fernando Matos Oliveira

Objectivos:

Este curso visa pensar o conceito de género em contexto teatral, considerando

especialmente a sua relação com o devir das formas dramáticas, as práticas de

representação e as diversas configurações sócio-culturais.

Conteúdos programáticos:

1. O conceito de género

1.1. Epistemologia;

1.2. História;

1.3. Crítica.

2. Mediações

2.1. Género e teatralidade;

2.2. Género e autoria;

2.3. Género e ideologia;

2.4. Formas teatrais e evolução tecnológica.

3. Tipologias

Descrição de um núcleo representativo de géneros teatrais antigos, medievais, clássicos,

barrocos, modernos, contemporâneos e orientais.

Bibliografia sumária:

A bibliografia será indicada ao longo das aulas.

1

1 - O conceito de géneros teatrais

. Epistemologia dos géneros

. Teatralidade e aquiteatralidade

. Os géneros na Poética

Conclusão: para além dos géneros

2

2 – Tipologias

. Géneros Medievais

. Sottie

. Drama litúrgico

. Sermão bufo

. Moralidade

. Mistério

. Farsa

. Entremez

….

. Géneros Clássicos e Neo-clássicos

. Tragédia

. Comédia

. Tragicomédia

…

. Géneros Barrocos

. Comedia dell’arte

. Pantomima musical

. Ópera

. Opereta

. Teatro de marionetas

. Teatro de cordel

. Zarzuela

…

. Géneros Modernos e Contemporâneos

. Drama

. Melodrama

. Drama lírico

. Vaudeville

. Teatro de revista

. Circo

. Agit-pop

. Happening

. Mimo

. Teatro de sombras

. Teatro documental

. Teatro épico

. Performance

. Instalação

. Perfinst

. Teatro virtual

…

. Géneros Orientais

. Noh

. Kabuki

…

3

4

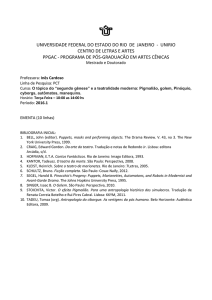

Bibliografia:

1- Epitemologia

AA. VV.

(1984) Teoria e storia dei generi letterari. La letteratura in scena. Il teatro del Novecento TirreniaStampatori.

Fowler,

(….) Kinds of Literature, Oxford.

Hernadi, Paul

(1972) Beyond Genre. New Directions in literary Classsification, Ithaca, Cornell UP.

Recursos na Internet:

http://www.theatrelibrary.org [geral]

http://www.theatrelibrary.org/links/TheatreGenres.html [

http://www.geocities.com/diteatro/terminos.html [géneros teatrais]

5

Géneros Teatrais

Este curso, constituído por um semestre único, pretende pensar os géneros em

contexto teatral, estudar as suas modalidades, convenções, modos e práticas de

representação, enquanto conceitos fundamentais ao entendimento das formas teatrais e do

seu papel social e cultural.

1 - O conceito de género

1.1. Epistemologia

. O que é um género?

A questão dos géneros tem constituído questão controversa desde Platão, o

primeiro que se terá referido à questão, até aos nossos dias. Trata-se de um assunto de

interesse não só para a praxis literária, mas também no âmbito da teoria literária.

Naturalmente falar em géneros literário motiva hoje desconfiança, pois os tempos

não correm de feição a convencionalismos apriorísticos como os que regulam a escrita

serva da prescrição genológica. Esta má fam vem de uma longa e secular tradição

prescritiva relativamente à criação literária.

Trata-se, antes de mais, de uma questão factual para o leitor comum, habituado a

ver na capa de alguns livros que lê referências como «romance», «drama» etc. etc. Mesmo

quando questionado sobre as suas preferências, frequentemente, o leitor gosta mais de ler

comédias do que ler uma tragédia. Os próprios livros que nos falam sobre literatura nos

apresentam os textos divididos em categorias que progressivamente vão modelando o

nosso olhar sobre os textos. São também estas razões eminentemente pragmáticas que

têm sustentado a pertinência dos géneros: na produção e recepção.

Portanto, se o enfado cresce de um lado, o conceito de género mantém uma grande

operatividade nos estudos literários, além de constituir um critério crítico de razoável

objectividade, sobretudo no campo incerto do discurso crítico.

Além do mais estão em causa implicações teóricas de diversa ordem, como

sejam:

- a possível existência de determinados universais (Antropologia; Filosofia)

- em termos semióticos, a categorização por E e por R, num plano da leitura lit.

- a própria criação literária (mudança, imitação, regras etc.);

Levantam-se, assim questões como:

- Todas as obras pertencem necessariamente a um género ?

- O que é afinal um género para o escritor e para o leitor ?

- Existirão sempre os mesmos géneros ?

- Porque haverá escritores bons em apenas um género ?

- Como surgem os géneros ?

- Que teorias existem sobre os géneros ?

6

Num plano histórico os géneros surgem com certa evidência. Alguns géneros tome-se a "epopeia" - são actualizados e praticados para, logo depois, o deixarem de ser.

Há que saber compreender estas variações históricas num plano não exclusivamente

literário, mas também social e humano.

Os géneros são testemunho (como o foram atrás a questão a intertextualidade) da

temporalidade de toda a escrita, também da literária. Não por acaso formalistas como

Tynianov encontraram no género um aliado precioso para a análise da evolução histórica

da literatura.

Ex: El Quixote e seu significado para a narrativa moderna.

O género é, então, um modo particular de uma obra se relacionar com a tradição

literária, sobretudo com aquela que com ele imediatamente partilha a sua condição

genológica, a sua convencionalidade mais ou menos presente.

Ex: A paródia é, neste sentido o máximo de consciência histórica en relação

a um género particular.

Porque nenhuma obra é no seu discurso ou na sua forma radicalmente única,

costuma dizer-se que essas afinidades, sejam elas de que tipo forem, conformam um campo

de investigação a que Genette chamou transtextualidade (Introduction à l’architexte). Entre

as várias categorias com que Genette procura abranger esse espaço de geral onde o literário

existe, a referida transtextualidade, encontram-se as categorias do modo e género que aqui

buscamos.

Qualquer género literário, tome-se o soneto como exemplo, no sentido em que é

parte de um conjunto de afinidades entre vários textos, constitui um espaço de

arquitextualidade, assim definida por Genette em Palimpsestes (p.7):

«o conjunto das categorias gerais ou transcendentes - tipos de discurso,

modos de enunciação, géneros literários, etc. - de onde decorre cada

texto singular»

A opção por qualquer uma destas modelizações, enquanto específica

normatividade, implica sempre o respeito pelas suas regras constituidoras.

Ex: Ler/escrever um romance, novela, tragédia etc. etc.

A relação texto/género é de extrema importância. Será da parte de cada um - do

aprendido e do oferecido de novo - que os juízos críticos normalmente se definem

havendo mesmo casos de textos particulares que, pela sua especificidade mais adiante se

instituem como verdadeiros géneros e modelos para outros.

Aspecto importante é considerarmos os vários tipos de sobredeterminações

arquitextuais portanto também a noção de género, e não as limitarmos apenas a certas

características formais ou estruturais. Assim, num plano de abstracção teórica é possível

considerar diversas forças arquitextuais. Efectivamente, ao abordarmos o problema dos

géneros, considerando as inúmeras propostas que historicamente tanto a prática como a

teoria literária têm vindo a apresentar, apenas podemos concluir que tudo se resume a a

uma classificação do todo literário segundo critérios:

- temáticos

- discursivos

- formais

7

Muitas vezes acontece até que apenas um destes critério ser dominante e não

exclusivo em certo texto.

Ex: Livro do Desassossego

É, aliás, na conjugação destes factores que historicamente se tem privilegiado a

tripartição entre narrativa, lírica e drama; e respectivos géneros. É assim que várias

propostas têm considerado factores e categorias classificativas tão variadas como as

seguintes:

- a forma em verso

- temas

- estilos (grotesco - W. Kaiser)

- mitos (ex: Prometeu) etc.

A existência de modos/géneros justifica-se, desde logo porque é credível que

em volta do fenómeno literário se registem factores mais ou menos universais e invariantes,

pois um idealismo anti-histórico dificilmente seria defensável quando aplicado a assuntos,

apesar de tudo humanos. Não é provável tudo pôr em causa em certo momento histórico.

A própria comunicação linguística só é possível porque decorre do respeito por um código

comum. De igual modo, a comunicação literária, no âmbito do sistema semiótico literário,

decorre sobre certas codificações propiciadoras da comunicação. Note-se que pertencer a

um género é já um passo decisivo para se poder possuir literariedade.

O fenómeno literário vive inevitavelmente rodeado de convenções que tanto

podem decorrer de atitudes universais do escritor face ao mundo e à vida como de

particulares condicionalismos histórico-sociais. Por esta razão podemos falar em modos e

géneros (Todorov, refere-se a géneros históricos e a géneros teóricos) enquanto duas realidades

diversas.

De um modo geral podemos afirmar que por detrás da noção de géneros está a

ideia da impossibilidade de um discurso singular, como se toda a “parole” não

escapasse à sujeição de uma qualquer “langue”. Tem-se associado esta condição interhumana de todo o discurso para justificar, pertinentemente, o género ao problema mais

geral dos géneros do discurso, entendidos na sua dinâmina linguística e não só literária,

notando como os intercâmbios discursivos têm sido uma constante histórica. É esta a

convição de Todorov ao se referir à questão da origem dos géneros.

Assim, num plano literário, falamos, no contexto da crítica literária ocidental, em

três níveis diferentes de sobredeterminação arquitextual:

. Géneros naturais e géneros não-naturais.

* Leitura e comentário do ensaio “La loi du genre”, de Jacques Derrida.

. “A lei da lei do género” (J. Derrida)

. Os géneros mistos;

. As marcas de género: participação e exclusão em simultâneo;

8

1.2. História;

. A institucionalização dos géneros;

. A tradição e o discurso sobre os géneros;

. O papel dos géneros na produção e na recepção artísticas;

* Leitura e comentário de «El origen de los géneros” (1987) de T. Todorov

9

1.3. Crítica

. Géneros e sub-géneros:

a) Género

Os diversos textos literários além de se filiarem em determinado modo inserem-se

em géneros propriamente ditos. Estes são categorias históricas e culturais, de carácter

instável e variável, que, mediante a pressão de factores endógenos (aparecimento

cumulativo de novos textos que promovam a evolução / transformação dos géneros) e de

factores exógenos (a acção do meio, transformações sócio-culturais, perdas de público por

parte de um género etc.)

Por outro lado, os géneros resultam já de uma codificação concreta ao nível

estilístico e semântico, embora o género 'romance' e Os Maias de Eça não existam num

mesmo plano, eles relacionam-se na medida em que um se poderia caracterizar como um

código regulador e o segundo como uma actualização prática desse código ainda devedor

de certa abstracção.

Outros aspectos importantes:

- os géneros e o cânone1: o género desempenha papel essencial na fixação do

cânone, pois a escolha das obras a considerar, estudar e a ler dependem grandemente do

impacto/recepção positivo ou negativo do género no público leitor e crítico. A própria

evolução literária deve-se também a esta relação do género com os receptores,

principalmente num tempo de indústria cultural acentuada, onde, como no texto de

Fialho, as modas se ditam ao mês.

Ex :

- hierarquias: devir do género desde o nascimento à 'morte' - o

'drama histórico' / o prestígio da epopeia etc.

- epopeia # romance ( contra-género )

- A origem dos géneros: eles têm como limite as possibilidades criadoras dos

homens, e são geralmente a institucionalização de práticas discursivas comuns. O género

resulta sempre da transformação de géneros anteriores. A sua historicidade deve ser

realçada:

Ex: drama - seu espaço significado modal e em termos de história cultural.

- Em termos semióticos o conceito de género revela-se ainda mais útil, pois a

comunicação literária, tanto na instância emissora (modelo de escrita) como na instância

receptora (horizonte de expectativas), é facilitada pela mediação do género.

- Os géneros são afinal mais um modo de classificar o todo, só aparentemente

indiferenciada, dos textos produzidos, eles são classes de textos. Fala-se mesmo numa

hierarquia de géneros, da acordo com a questão da sua valoração.

- Podemos distinguir os géneros literários predominantemente segundo princípios

de natureza semântico-pragmática (écloga: associa-se à utopia, melancolia, idade mítica

do ouro) e de natureza técnico-compositiva (soneto: duas quadras e dois tercetos ).

1

Alastair Fowler, " Genre and the literary canon" in: NLH , XI, I (1979), 97-119.

10

- Do que se disse resulta que o critério verso/prosa é insuficiente para a

classificação modal, embora seja um dado muito relevante em temos de história literária,

certa naturalização dos discuros (drama, romance/novela). Contudo, como vimos em

relação a fenómenos de intensificação pelo verso, é compreensível a preferência da lírica

pelo verso.

b) Sub-Géneros:

Como o nome deixa antever são unidades menores. No interior do código do

género a que pertencem acentuam certos traços formais ou semântico-pragmáticos. São

entidades ainda mais volúveis do que os géneros e geralmente de menor resistência

temporal, embora o 'soneto' se tenha vindo a afirmar como um sub-género de grande

vitalidade.

Ex :

- romance (picaresco, histórico, de formação, epistolar )

- écloga (pastoril, piscatória)

Concluindo, poderemos alertar para a profunda relação de interdependência entre

os géneros teatrais e a História do Teatro ou estilos de época, eles são sinais

privilegiados para o anunciar de mudanças.

Assim, o género não pode mais ser encarado numa perspectiva essencialista,

nominalista (o nome cria a coisa) ou autoreferencial2, mas como mero princípio operatório,

numa época pós-romântica que veio separar a história literária da crítica literária,

deixando o género de ser uma norma para avaliar da adequação ou desvio das obras, bem

como da sua composição. Sendo a evolução literária uma história de descontinuidades, o

género deverá ser visto como um conceito aberto, similar ao conceito Wittgensteiniano de

«semelhanças de família», rentável apenas no seu valor interpretativo, porque não

podemos deixar de considerar relevante as opções deliberadas por certas formas

comunicação literária.

Acresce o questionamento actual (pós-romântico) de toda a normatividade

criadora. Ainda assim, mesmo que se veja o momento actual como uma parodização

incessante (Linda Hutcheon), interessa-nos conhecer o objecto da paródia.

Ex: contínuas reescritas actuais de textos anteriores

2

Jean Marie Schaeffer, «Literary Genres» , in Ralph Cohen

11

2. Mediações

2.1. Género e teatralidade;

. Os géneros teatrais: a questão da teatralidade;

. Os conceitos de “drama”, “teatro”, “script” e “performance” (R. Schechner);

. A emergência da escrita como subjectivação do “script”.

2.2. Género e autoria;

. O género como programa

. Regras e criatividade

2.3. Género e ideologia;

. A historicidade dos géneros teatrais;

. ex: Tragédia - drama

. ex: Épica - romance

2.4. Formas teatrais e evolução tecnológica.

To understand the evolution in genres over time it helps to know the historical antecedent,

or what came before.

• As technology evolves, new forms of storytelling evolve.

• Oral cultures became print cultures after Gutenberg's invention of the printing

press.

• The advent of electrical conduction in the nineteenth century gave rise to what

we now call media,

• Print cultures are now electronic cultures.

• A Galáxia de Guttenberg, de Marshall McLuhan, Canadian communications theorist

• McLuhan spawned such common terms as the global village, mass media, and

most famously, the medium is the message and it's closely associated deriviative

the medium is the massage.

* Comentário de excertos de Simulacros e Simulação de J. Baudrillard.

* Ex: Canadian Institute for Theatre Technology http://www.citt.org

12

* Ex: Theatre Technology

The Foothill College Theatre Technology program prepares the theatre student for entrylevel positions in professional and community theatre. A comprehensive and intensive twoyear program, Theatre Technology offers the first-year student the opportunity to explore

fundamentals of a wide variety of practical career opportunities.

Students interested in stage management, theatre design of sets, props, costumes, lights,

sound, and scene painting are able to participate in both daytime lecture and laboratory

classes and evening production experiences. Foothill Drama department offers four to six

major productions during the academic year. Technical theatre students participate in the

hands-on experience of creating all of the technical elements of the productions. During

the summer quarter, technical theatre students participate in the production of a major

musical in conjunction with the Foothill Music Theatre. At the end of their first year,

students will be asked to choose a specific area to specialize in during the internship phase

of their second year.

CORE COURSES (19.5 Units)

DRAM 1 Theatre Arts Appreciation (4.5 Units)

DRAM 21A Fundamentals of Theatre Production (4 Units)

DRAM 72 Drafting for the Theatre, Film & Television (4 Units)

DRAM 49 Rehearsal & Performance (3 Units)

GRDS 56 Introduction to Computer Graphics (4 units)

SUPPORT COURSES (24 Units)

Choose 24 units from one of the areas of emphasis below:

Stage Management Emphasis

DRAM 8 The Multicultural Mosaic of Performing Arts in America (4 Units)

DRAM 21B, C Fundamentals of Theatre Production (4-4 Units)

DRAM 49X or 49Y Rehearsal & Performance (4-5.5 Units&Mac226;)

DRAM 71 Fundamentals of Stage Management (4 Units)

DRAM 72 Drafting for the Theatre, Film & Television (4 Units)

CWE 51 or 52 Internship in Stage Management (1-8 Units)

Stage & Shop Technology Emphasis

DRAM 8 The Multicultural Mosaic of Performing Arts in America (4 Units)

DRAM 21B, C Fundamentals of Theatre Production (4-4 Units)

DRAM 42A Introduction to Scene Design (4 Units)

DRAM 72 Drafting for Theatre, Film & Television (4 Units)

DRAM 73 Technology in Wood & Fabric (4 Units)

DRAM 78 Technology in Steel & Related Materials (4 Units)

CWE 51 or 52 Internship in Stage & Shop Technology (1-8 Units)

Costume Technology Emphasis

DRAM 8 The Multicultural Mosaic of Performing Arts in America (4 Units)

DRAM 21B, C Fundamentals of Theatre Production (4-4 Units)

DRAM 42A Introduction to Scene Design (4 Units)

13

DRAM 75 Introduction to Costume Technology (4 Units)

DRAM 76 Introduction to Costume Design (4 Units)

CWE 51 or 52 Internship in Costume Technology (1-8 Units)

Stage Lighting Technology Emphasis

DRAM 8 The Multicultural Mosaic of Performing Arts in America (4 Units)

DRAM 21B, C Fundamentals of Theatre Production (4-4 Units)

DRAM 42A Introduction to Scene Design & Painting (4 Units)

DRAM 72 Drafting for Theatre, Film & Television (4 Units)

DRAM 77 Introduction to Lighting Design & Technology (4 Units)

CWE 51 or 52 Internship in Lighting Technology (1-8 Units)

Scenic Design & Painting Assistant Emphasis

DRAM 8 the Multicultural Mosaic of Performing Arts in America (4 Units)

DRAM 21B, C Fundamentals of Theatre Production (4-4 Units)

DRAM 42A Introduction to Scene Design & Painting (4 Units)

DRAM 72 Drafting for Theatre, Film & Television (4 Units)

DRAM 73 Technology in Wood & Fabric (3 Units)

DRAM 79 Model Building for the Theatre, Film & Television (4 Units)

CWE 51 or 52 Internship in Stage Design (1-8 Units)

* Comentário de Johannes Birringer intitulado «Postmodern Performance and

Technology», in Theatre, Theory, Postmodernism, Bloomington/Indianapolis, Indiana

University Press, 1991, pp. 169-181 [or.: Performing Arts Journal, 1985, Nº 26/27]

14

3 - Tipologias

3.1. Géneros Antigos

Das procissões dionisíacas ao palco das tragédias

As procissões dionisíacas contavam a história da vida do deus Dioniso, de um modo

análogo às procissões da Semana Santa cristã, em que a vida, paixão, morte e ressurreição

de Jesus Cristo é relembrada.

Na vida de Dioniso (dê uma olhada no artigo que publicamos em março), há dois

momentos bastante diferentes: quando ele é destruído pelos Titãs (morte, tensão) e quando

ele renasce (alegria, extroversão). Já sabemos que estes dois momentos têm significados

relacionados ao ciclo da natureza, no qual a semente fica enterrada por alguns meses, para

enfim, surgir, germinada. No momento da morte de Dioniso eram entoados cantos, tristes

e solenes, chamados ditirambos. A tragédia é uma forma dramática surgida na Grécia, no

século V a.C., originada do ditirambro (canto em louvor a Dioniso). Etimologia (origem) da

palavra tragédia: tragos (bode) + oide (canto) = canto do bode, animal que relembra um

dos "disfarces" usados por Dioniso.

O desenvolvimento do pensamento grego apresenta dois momentos fundamentais: século

XVI a.C. até o século IX a.C., quando a sociedade e o pensamento apoiavam-se no mito

para encontrar explicações para os fenómenos na natureza e para a vida em geral. E a partir

do século VIII a.C. quando surge a pólis, o pensamento filosófico e a valorização do

racional, que vão recusar a visão de mundo anterior (baseada no pensamento mítico).

O teatro surge como novidade artística, na Grécia do século V a.C., trazendo normas

estéticas, temas e convenções próprias. Pode-se dizer que o teatro explica o contexto

histórico de século V, da mesma forma que o contexto daquele momento se apreende

melhor através das peças então produzidas, demonstrando a profunda interrelação entre

sociedade e teatro.

Os festivais de Teatro

O teatro grego nasceu da religião e mesmo após todas as transformações pelas quais passou

não perdeu de vista as suas origens. As representações dramáticas em Atenas realizavam-se

três vezes por ano, por ocasião das festas dionisíacas:

Dionísias Urbanas ou Grandes Dionísias - eram celebradas na primavera (fins de março) e

freqüentadas por toda a população grega, além de embaixadores estrangeiros. A festa

durava seis dias. O primeiro era consagrado a uma solene procissão, em que toda a cidade

tomava parte. Nesta procissão se levava a estátua do Deus Dioniso que era finalmente

colocada na orquestra do Teatro de Dioniso. Nos dois dias seguintes celebravam-se os

concursos de dez coros ditirâmbicos. Os concursos dramáticos ocupavam os três últimos

dias. Eram escolhidos três poetas trágicos, que representavam, cada um deles, sua obra

inteira, num mesmo dia. Ou seja, três tragédias e um drama satírico (tetralogia).

Leneanas - tinham um caráter mais local. Celebravam-se no inverno, fins de janeiro e

duravam de três a quatro dias. Uma procissão, de cunho extremamente licencioso e um

duplo concurso e comédias e tragédias, eram as atrações da festa.

15

Dionísias Rurais - celebravam-se apenas nos "demos" (povoados) nos fins de dezembro e

eram as mais antigas festas de Dioniso, dependendo o brilho de tais festejos dos recursos

do demos.

A preparação das "Grandes Dionísias" ficava sob a responsabilidade de um funcionário do

governo que recrutava os coregos (cidadãos ricos que patrocinavam os coros) e com isso,

garantia a produção do espetáculo. A coregia era um dos serviços públicos impostos pelo

Estado ateniense aos cidadãos ricos. Com financiamento garantido, tanto para os ensaios

quanto para as representações teatrais, que se realizavam obrigatoriamente três vezes ao

ano, o corego recrutava atores, profissionalizava-os, selecionava os poetas competidores,

encarregava-se da parte organizacional do espetáculo, garantia o acesso de todos os

cidadãos aos espetáculos, com direito a uma ajuda de custo para o pagamento dos ingressos

e das refeições nos dias de festivais, para os mais pobres.

A especialização das atividades teatrais atinge tal nível na Atenas clássica que o Estado

estabelece uma legislação sobre o fazer teatral, estipulando critérios de seleção dos actores

para os principais papéis e seus substitutos, distribuição dos personagens e recrutamento

dos coreutas (integrantes do coro que contracenavam com os atores).

No final dos concursos dramáticos realizava-se um julgamento, de onde resultava a

classificação final dos concorrentes. Eram três categorias premiadas: poetas, coregos e

protagonistas. Essa classificação era votada por um júri, que dava seu veredicto sob forma

de voto secreto.

As representações em Atenas começavam pela manhã. E se assistia ao espectáculo

com uma coroa na cabeça, como nas cerimónias religiosas. As mulheres atenienses, embora

não pudessem participar da cena, podiam assisti-la como espectadoras, pelo menos da

tragédia. Quanto à comédia, devido a certas liberdades inerentes ao género, não era

freqüentada pelas atenienses mais "sérias".

Os géneros antigos

. Tragédia

. Comédia

16

3.2. Géneros Medievais

3.2.1. Recursos:

- http://www.hottopos.com/videtur22/jean_teatro_mediev.htm

- http://web.ccr.jussieu.fr/urfist/menestrel/theatre/textes.htm

- Vídeo da “Escola da Noite” com encenação vicentina Uma visitação;

- Vídeo com a Festa D’Elx;

3.2.2. A teatralidade medieval: introdução

A questão dos géneros é de difícil enquadramento na Idade Média, pois estamos sobretudo

perante práticas espectaculares que nem sempre partem de uma textualidade prévia. A

noção clássica/moderna de um texto + encenação não é aplicável a grande parte do

espectáculo medieval de teor porfano ou religioso.

Não há continuidades evidentes entre o teatro clássico e o teatro medieval, com excepções

das comédias da monja Rosvita de Gandersheim (c. 935-973)

O teatro como que foi ‘reinventado’ na Idade média;

O jogral é a figura que na IM protagoniza o espectáculo, conjugando dança, o jogo, a

acrobacia, a mímica e a música. É uma actividade exercida em regime nómada. Acolhe um

amplo número de temas: gesta, matéria da Bretanha, mitologia, hagiografias, falbiaux, etc. É

ainda uma cultura predominantemente oral; a cultura jogralesca é também aproveitada pela

igreja.

Os momos estavam mais ligados à diversão aristocrata e não representavam textos, antes

assumindo a animação lúdica e acrobática da corte.

O território do teatro medieval pode ser esquematicamente resumido ao seguinte de [cf.

Francesc Massip, 1992]:

3.2.2.1. Teatro de diversão

a) A tradição clássica:

Muito escassa e só verdadeiramente desenvolvida ao longo do renascimento Quinhentista;

b) A tradição popular:

A festa representa um encontro entre as tradições pagãs/agrícolas e as tradições religiosas.

Os géneros cómicos. A festividade medieval organiza-se em ciclos relacionados com o

Solstício de Inverno, o solstício de Verão (associado ao Pentecostes), o Corpus Christi e a

festa de Todos os Santos. Assiste-se a uma progressiva cristianização destas práticas

festivas. A Igreja responde com a celebração do Nascimento, desde logo adulteradas pelas

17

figuras admissíveis dos loucos e crianças, em paródias litúrgicas como os officium

stultorum, officium asinorum, etc. Ressaltam as seguintes festividades, as quais acolhem o

encontro da teatralidade pagã com o mundo cristão, em espectáculos de rua de vária índole:

. Carnaval

. Semana Santa / Páscoa – Paixão, Morte e Ressurreição de Cristo

. Dança da morte - risus paschallis

. Festas primaveris

c) Os géneros cómicos:

Os géneros cómicos eram dominantes neste espaço.

* Sermão bufo

Versão paródica da textualidade litúrgica; monólogo de tema e composição livres;

* Sottie

Peça cómica, representada pelo Carnaval, a cargo de associações de confrades ou sots. O

sot é define-se pela calvice, assume a carapuça do louco, vestido com jubão curto e calça

apertada; cor amarela simboliza a alegria e a loucura. A sottie integra-se em espectáculos

mais alargados, nela participam vários elementos.

É parte dos géneros cómicos do séc. XV em França: Au XIVe siècle, il y a une

véritable éclipse du théâtre comique, alors qu’il triomphe au milieu du siècle suivant grâce à

des confréreries de clercs et d’étudiants (les clercs de la Bazoche ; les Enfants sans souci).

Coexistent quatre genres :

- La sotie ou sottie : jouée par des «sots» ou «fous» : scènes bouffonnes,

mais toujours satiriques.

- Le monologue : un seul personnage dont les discours révèlent les travers.

- La moralité : genre didactique, par l’emploi abondant des allégories, et

assez ennuyeux...

- La farce : le genre comique le plus durable. Recours aux thèmes et

situations les plus universelles pour faire rire le plus vaste public : l’adultère,

la filouterie etc. Ex. La farce du Cuvier ; La farce de Maître Pathelin (1464).

Danièle Buchler, Le bouffon et le carnavalesque dans le theatre français, Univ. Florida, 2003

http://www.phys.ufl.edu/~daniele/Thesisshort.pdf

. Recueil général des sotties.

http://web.ccr.jussieu.fr/urfist/menestrel/theatre/textes.htm

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/Visualiseur?Destination=Gallica&O=NUMM-5086

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sotie

* Entremez

Representações episódicas de carácter jocoso, muitas vezes inseridas em unidades

dramáticas ou espectaculares de maior dimensão; poderiam ser protagonizados por

momos, como nos surge no cap. 127 de Vida e feitos de D. João II, de Garcia de Resende:

18

«E veo outro entrmês muito grande em que vinham muitos momos em ~ua fortaleza antre

~ua rocha, e mata de muitas …»

Estamos perante um quadro sem acção estruturada, baseado em elementos

narrativos/actanciais elementares, como a luta entre o cavaleiro e os selvagens etc.

Ex: Floresta de Enganos de Gil Vicente: uma comédia, dois entremezes e intróito

* Fabliau français

Le terme, d'origine picarde, correspond à l'ancien français fableau et a été introduit dans

l'usage critique par J. Bédier à la fin du XIXe s. Il apparaît dans cinquante-six textes que

l'on a qualifiés pour cette raison de fabliaux certifiés : par extension, il sert aujourd'hui

d'appellation générique à près de cent cinquante oeuvres brèves en octosyllabes (à une

exception près) qui présentent des caractères analogues. [...] Le fabliau voisine avec

plusieurs genres auxquels il peut emprunter çà et là plusieurs traits : le lai, le conte

moral, l' exemplum , le dit, la fable, quelquefois le débat ou la nouvelle courtoise.

Tous ces genres ont en commun la brièveté, et la terminologie médiévale les confond

parfois derrière l'usage de termes comme « conte », « dit » ou « essample ». Peut-être le

critère stylistique est-il en fait le plus pertinent eu égard à la grande variété des thèmes et

des tons : style bas, prédominance narrative, thématique triviale. Ces critères peuvent

cependant s'accommoder, dans les meilleurs fabliaux, d'ornements rhétoriques à

caractère ludique (paronomases, jeux de sonorités, jeux sur le rythme, rejets insolites). [...]

La production des fabliaux est limitée à la France du Nord, de langue d'oïl. La Picardie,

l'Artois et la Normandie sont les régions les mieux représentées ; viennent ensuite les

provinces du centre (Bourgogne, Champagne, Orléanais) ; quelques fabliaux pourraient

provenir de l'Ouest. La plupart sont anonymes, d'autres sont dus à des auteurs dont nous

ne connaissons que le nom : Drouin de Lavesne, Eustache d'Amiens, Hugues Piaucele,

Gautier le Leu, Huon de Cambrai, Croulebarbe... . Quelques-uns enfin sont signés par des

auteurs bien connus par ailleurs : Jean Bodel, Rutebeuf, et, au XIVe s., Jacques de Baisieux,

Jean de Condé ou Watriquet de Couvins. Relativement circonscrit dans l'espace, le fabliau

l'est aussi dans le temps : les premiers textes apparaissent vers la fin du XIIe s., les derniers

ne franchissent pas les années 1340. [...]

L'audience des fabliaux (dont la diffusion était mi-écrite, mi-orale) ne se limite pas à un

public bourgeois ou aristocratique. Il existe d'ailleurs parfois des versions différentes d'un

même fabliau qui témoignent de références sociales distinctes (ainsi des Tresses , d'esprit

plus aristocratique que son semblable, La femme qui fit entendre à son mari qu'il sonjoit ). La

question du public destinataire a longtemps divisé la critique: c'est souvent une fausse

question, les fabliaux prennent généralement le parti de la jeunesse contre les gens établis

(paysans riches, prêtres ruraux ou chevaliers). [...]

L'illusion joue ainsi à tous les niveaux : les fabliaux, ou du moins les meilleurs d'entre eux,

sont des jeux de masques. Daí a sua configuração paródica, com mais de um actor.

La ruse, l'un des pivots des intrigues, appartient donc à l'esthétique autant qu'à la narration.

Elle triomphe d'autant plus qu'elle est toujours ici un signe de vitalité : lorsqu'elle ne l'est

pas, elle tourne court au profit de contre-ruses plus virtuoses. C'est un point commun

important avec le Roman de Renart : tous deux s'intéressent d'ailleurs à tous les types de

19

décalages entre les comportements et la norme et de falsification du réel. Le jeu et la

dimension morale sont donc, paradoxalement, in-séparables. [...] - Dominique Boutet,

professeur, Paris X-Nanterre

* Farsa

Suporte narrativo; pequeno número de personagens; texto curto; personagens ‘realistas’;

presença de enganos ou burlas, elementos centrais; com um ou mais núcleos actanciais;

pode decorrer de forma autónoma em palcos profanos, nas feiras, acompanhada por

gestualidade exagerada etc. Temas em torno da autoridade, das funções naturais, do

aspecto físico e do carácter.

On distingue traditionnellement ces pièces - pour lesquelles le qualificatif ancien de

« joyeuses » semble le plus approprié - des autres formes comiques brèves: le sermon

joyeux, à une voix, essentiellement parodique ; la sottie, à plusieurs acteurs, mais dont

l'incidence est plutôt parodique.

Pièce généralement courte (autour de 500 v. : le texte qui sert d'archétype, la Farce de

maistre Pathelin , est atypique), en octosyllabes à rimes plates surtout, la farce développe une

action dramatique simple aux rôles schématiques et stéréotypés. Le rythme, le jeu des

acteurs y tiennent une place considérable ; les échanges verbaux empruntent volontiers aux

procédés du rire les plus immédiats, scatologie et obscénité.

La représentation se fait sur un « échafaud », une petite estrade de 2 x 3 m, à 2 m.

du sol, entouré de public sur trois côtés et limité sur le quatrième par une tenture ; les

acteurs sont tous des hommes et les rôles sont codifiés (le badin au visage enfariné,

avec un bonnet d'enfant et souvent bossu, encore vivant chez Marot et Rabelais). Les gags

visuels, le jeu physique des acteurs, la manipulation d'objets facétieux (flacons d'urine,

braies d'une propreté douteuse) tiennent une place importante : c'est la tradition que

prolonge la commedia dell'arte . Le scénario va de la simple parade (Les femmes qui font

rembourrer leur bas exposant le procédé sans détours sur la scène ; l' Obstination des femmes est

une simple dispute sans issue) à la construction d'une intrigue sophistiquée. Le trait

déterminant de la farce est alors l'extériorité de l'action, la priorité de la structure : le

personnage est une sorte de pantin, soumis aux règles implacables d'une mécanique - la «

machine à rire ».

3.2.2.2. Teatro de edificação

No século IX o drama voltou aos palcos desta vez na Igreja. Normalmente

eram histórias bíblicas e eram representadas por padres. Estas representações na Igreja

eram uma forma de estabelecer uma ligação com a comunidade, uma comunidade ainda

assente nos rituais e superstições pagãos. Assim a Igreja utilizou-se do drama de modo a

ilustrar as histórias bíblicas, histórias que explicavam as festas católicas (que antes haviam

sido festas pagãs). Reforçava assim a sua conotação religiosa e conseguia melhor comunicar

com uma congregação na sua maioria iletrada.

É irónico pensar que tenha sido a Igreja a acabar com o Teatro e ao mesmo tempo o tenha

mantido vivo ao longo dos anos.

A popularidade dos dramas começou a crescer, passando das Igrejas para o ar livre,

normalmente em frente aos templos.

20

* A missa

Cerimónia central do Cristianismo, segundo J. Genet «o drama mais perfeito do mundo

ocidental».

* O drama litúrgico

O teatro medieval - como a literatura e outras produções artísticas da época - comporta,

tipicamente, um outro objectivo: o de instruir. Indissociável da Idade Média é, também, o

elemento religioso: o teatro medieval surge - como que naturalmente - da liturgia,

principalmente da liturgia da Páscoa.

Com o tempo, verifica-se uma complexificação do ritual litúrgico. Assim, em

algumas abadias beneditinas, a liturgia passa também a representar episódios da vida de

Cristo, sobretudo os da Ressurreição (as antífonas [refrão] são já uma plataforma de

lançamento para o teatro): Há toda um a teatralidade que se desdobra a partir do ritual

(Massip, 1992), incluindo já cerimónias dialogadas:

. Visitatio Sepulchri (recolhidas em 970 pelo bispo de Winchester)

. Officium Peregrinorum

. De Tribus Mariis (Catedral de Vic, séc. XII)

O drama litúrgico é cantado em latim. Um texto inglês do séc. IX descreve o

acompanhamento da leitura litúrgica do Evangelho*:

ORDO

(Durante a terceira leitura, quatro irmãos mudam de veste. O primeiro, com trajes brancos, entra com ar

de quem está preocupado com uma tarefa, penetra no sepulcro e senta-se em silêncio, segurando uma palma

na mão. Depois, enquanto se recita o terceiro responsório, entram os outros três irmãos, revestidos com

capas, trazendo nas mãos turíbulos com incenso e, lentamente, como quem procura algo, dirigem-se ao

sepulcro. Com esta cena, representa-se o anjo sentado sobre o sepulcro e as mulheres que chegam com aromas

para ungir o corpo de Jesus. Mal o irmão sentado vê aproximarem-se os outros três - com ar titubeante, de

quem está procurando alguma coisa -, começa a cantar suavemente, a meia-voz:)

- Que buscais no sepulcro, ó cristãos?

(Ao que os três respondem, cantando em uníssono:)

- A Jesus Nazareno crucificado, ó habitante do Céu.

- Não está aqui, ressuscitou como tinha predito! Ide e anunciai que Ele superou a morte!

(Os três dirigem-se ao coro, cantando:)

- Aleluia, o Senhor ressuscitou, hoje o leão forte ressuscitou, o Cristo, Filho de Deus.

(Depois destas palavras, o irmão torna a se sentar e, como que chamando-os, entoa a antífona:)

- Ressuscitou do sepulcro o Senhor que, por nós, esteve na Cruz. Aleluia.

21

(Estendem o sudário sobre o altar. Terminada a antífona, o prior, para expressar a alegria pelo triunfo de

nosso rei, ressuscitado depois de ter vencido a morte, ecoa o ‘Te Deum laudamus’ e todos os sinos tocam

juntos.) (*) Cit. por Nilda GUGLIELMI, El teatro medieval, Edit. Universitaria de Buenos

Aires, 1980, pp.12-13.

. Cf. «Liturgia y drama», in Massip, 1002 :35-36.

22

* O mistério :

Maior acessibilidade enquanto narrativa da humanidade sacrificial de Cristo.

. Ludus de Passione, in Carmina Burana (séc. XIII) : enfatiza a dor da Paixão

. Ordo Representacionis Ade,

. Le miracle de Théophile, mistério mariano, do jogral Rutbeuf

. Miracles de Nôtre Dame par personnages; 4º mistérios

. Miracle plays do Ciclo de York

A partir dos Séc- XIV começam a surgir mistérios celebrados nas línguas vulgares, com

base em poemas narrativos da Paixão, recitados por jograis. Verifica-se uma humanização

temática.

As festividades do Corpus Christi começam a ser acompanhadas de composições de

índole pagã, fundindo várias tradições espectaculares;

[Mystere dou jour dou jugement]

Besançon, Bibliothèque Municipale ms. [M] 579

http://www.byu.edu/~hurlbut/dscriptorium/jugement/jugement.html

The manuscript of the 14th-century mystery play 'The Day of Judgment,' includes roles for

94 characters, 89 miniatures depicting the action of the play and three neumed musical

pieces. Grace Frank gives this plot summary in The Medieval French Drama, (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1954), pp. 132-33:

"After an introductory sermon by Le Prescheur we find Satan and his devils preparing to

send one of them, disguised as an elegant youth, to seduce a woman of the tribe of Dan in

Babylon. This devil, Angignars, speedily accomplishes his purpose and Antichrist is born of

the union. The devils now begin instructing Antichrist in all their arts, and presently he is

able to make the blind to see, to cure the leprous, rivive the dead, and heap riches upon the

poor. He readily wins over the Jews and grows so powerful that even kings and cardinals

pay him homage. Only the Pope himself and Enoch and Elijah who have been sent by

God to wage war against the enemy are able to resist the magic of Antichrist.

[. . .] Antichrist is overthrown, Enoch and Elijah who have been killed by his orders are

resurrected, and the damned, as in so many poems concerned with the Harrowing of Hell

or the Dance of Death, pass in review before us. Here they include an abbess and bishop

who have sinned together, a king, bailiff, provost, lawyer, adulterous queen, erring prioress,

a usurer, his wife, his servant, and even his small child. Although eight pages of the

manuscript are missing, it is obvious that the God of our author was especially

condemnatory of all who lived on the fruits of usury and was especially concerned with

those who were kind or unkind to the poor . . . . In the final reckoning angels pour out

vials of wrath, apostles and saints aid in the task of separating saved from damned, and

eventually the just are duly rewarded and the wicked driven to hell by menacing devils. The

play ends with a few unique lines of seven syllables spoken by St. Paul, who says that the

damned have been taken to hell for eternal torment."

23

The images in this directory are scans from color photographic enlargements made from

35mm negatives. In most cases, the miniatures occupy less than .5 square cm of negative

space and the resulting scans are, therefore, somewhat blurred. Many of the original

miniatures are also either dark or damaged. Each of the scanned images has been enhanced

to reduce the blur and in some cases lightened. The trade-off is a slight graininess which

may be detected on higher resolution monitors. The file en-sampl.jpg includes samples of

an image before and after enhancement. All enhancements were made using TIFFany on a

NeXT Dimension workstation.

The Music

jdj-101 - Fols. 8v(d)9r(a) / Angels singing to Enoc and Elias.

The Miniatures

Descriptions of each miniature are from the most recent edition of the play by Emile Roy

(Paris: Emile Bouillon, 1902). [Enhancements listed in brackets]:

24

Fol. 2v / Le Jugement dernier

Fol. 3r - Le sermon du Prêcheur

25

Fol. 6r / Le diable Engignart et le Matan en vue

d'un buisson

26

* A moralidade

Pièce de théâtre non religieuse, mais fondamentalement didactique, où l'allégorie

régit les figures et l'action. Personagens são abstractos e personificam vícios e virtudes

(cf. Gil vicente). Le terme « moralité » apparaît en 1427-1428 (deux pièces jouées au

collège de Navarre, où il est question de « choses par exemples monstrées », de

«personnages, exemples et figures »). Il est assez difficile de circonscrire le corpus (les

limites entre moralité et sottie sont floues), mais on peut définir le type : une moyenne de 1

500 vers, une volonté didactique affichée. Avec l'exemplarité de l'intrigue et la fixité des

acteurs, les fondements aristotéliciens de la pratique théâtrale antique sont abandonnés : la

vraisemblance psychologique, la notion de « caractères moyens », l'historicité de l'action, la

contingence des événements dramatiques, créatrice de tension, tout cela n'a pas cours. La

Moralité ne connaît pas le hasard ou le suspense : aucune incertitude sur le dénouement,

inscrit dans le canevas, expliqué par le prologue, marqué dans le nom et dans le discours

des acteurs, ressassé par des anticipations systématiques ; nous sommes ici dans la

répétition, dans la représentation de l'ordre. Elle repose sur l'emploi massif de la figure

de personnification. Le spectre des réalités est plus large que dans la tradition littéraire :

notions morales (Vices et Vertus), parties du corps, maladies, argent, temps, pouvoir,

entités métaphysiques, etc. L'une des inventions du genre est le personnage incarnant

l'homme dans la société : Homme, Chacun, Tout le Monde, Gens ou le Groupe, comme

Petit et Grand, Marchandise et Métier, Pauvre Commun...

Les schémas d'action manifestent peu d'indépendance par rapport à la tradition

allégorique. On y trouve tous les canevas familiers sur les deux grandes métaphores de

l'itinéraire et du conflit. Le voyage est actualisé dans les déplacements sur l'aire de jeu, avec

des stations dans des « mansions », selon une logique de l'ascension ou de la déchéance,

elle-même matérialisée (degrés, étages, chutes) ; batailles, procès et altercations sont les

variantes de l'antagonisme, qui peut être une véritable Psychomachia (Langue envenimée,

Homme juste et Homme mondain).

Le procès rencontre autant de succès que dans les livres ( L'Homme pécheur , Le Gouvert

d'humanité , Le Nouveau Monde ), mais on se contente parfois d'une simple querelle de

préséance ( Pèlerinage de vie humaine , Ventre et les jambes et tout , qui s'inspire de la fable de

Ménennius Agrippa, Rien et chacun ). En arrière-plan de tous ces schémas, le choix entre

Bien et Mal, ou la critique politico-sociale sur les abus du temps présent : l'allégorie sert

alors de masque commode pour la polémique. [Armand Strubel]

27

3.2.2.3. Teatro de rito civil e espectáculos de poder

* Banquetes

* Entradas régias

* Torneios

3.2.3. O Espaço da representação medieval

Não há reflexão explícita, apenas esboços e desenhos.

Mas temos espaço estruturado cenicamente;

Os espaços ‘teatrais’ resultam da transfiguração do espaço quotidiano/religioso

O palco italiano será futuramente uma imposição do olhar privilegiado do príncipe…

Não há ainda espacialidade autónoma

Espaço povoado de adereços e objectos identificadores, em contiguidade com o..

A Igreja como encenação cósmica:

. nave – procissões

. presbitério/capela-mor – ritos diários

. coro –

. altar-mor –

.

Pórtico es una galería cubierta al aire libre. Logia es el conjunto que está formado

por un entablamento sostenido por dos columnas, en medio de las cuales hay una

arcada. Atrio (Roma) es el patio interior de una casa, hacia el cual se orientaban las

habitaciones, en el Bizancio el atrio es un patio que precede a un monumento y en

el cristianismo es el emplazamiento anterior a las iglesias cristianas. Nave es la parte

de la iglesia que se extiende desde el altar mayor a la portada Principal. Crucero es

el espacio comprendido en el cruce de la nave mayor con otra. El Transepto es la

nave que cruza con la central cerca del altar mayor. Cripta es la capilla o iglesia

subterránea. Abside es la extremidad de una iglesia situada detrás del coro. Girola es

una nave circular con capillas en el ábside. Triforio es la galería superior que corre

sobre las naves laterales de las iglesias.

O nascimento do espaço urbano

A ideia da praça/centro

Espaço teatral é habitado

A cena medieval é simultânea: várias acções na processão

A cena central

. espaço circular

. espaço ortogonal, mais fácil no espaço urbano

A cena integrada – dentro da igreja

. horizontal

. vertical (importante)

. linear (desfiles, entradas régias)

28

A procissão do Corpus Christi

A progressiva estabilização/frontalização cénica na Igreja

3.2.4. As técnicas da representação medieval

Cenografia medieval

Decoração

Vestuário

As máquinas de cena (cordas,

Truques e artifícios (tintas, fumos…)

Máscaras (Diabo …)

Efeitos especiais: sobretudo nas cenas sobrenaturais

Música instrumental ou vocal

A direcção de cena (maestro, diácono, a figura do director de cena…)

O actor

3.2.5. A recepção do teatro medieval

O teatro medieval é um evento sócio-artístico

Muito centrado na audiência (dif. estética conceptual moderna)

Bibliografia:

Bernardes, José Cardoso

(1996) Sátira e Lirismo. Modelos de Síntese no Teatro de Gil Vicente, Coimbra, Imprensa da Univ.

de Coimbra.

Knight, Alain

(1983) Aspects of Genre in Late Medieval Drama. Manchester, UP of Manchester.

Massip, Francesc

(1992) El Teatro medieval. Voz de la divindad cuerpo de histrion, Madrid, Montesinos.

29

3.3. Géneros Clássicos e Neo-clássicos

3.3.1. Recursos

- Vídeo com representação de Mandrágora/Maquiavel, pela Escola da Noite

- El generro teatral en la Antiguidad: http://club2.telepolis.com/mandragora1/genero.htm

3.3.2. O teatro renascentista: introdução

Uma tradição erudita (# teatro popular)

A linha vitruviana

. Tradução para o inglês de Morris Hicky Morgan – Vitruvius: The Ten Books On

Architecture. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1960. (Tradução para o português: prof.

Frederico Flósculo Pinheiro Barreto – Depto. de Projeto, Expressão e Representação da FAUUnB)

. Apresentamos para os estudantes de Arquitetura e Urbanismo este interessante

texto "fundador" da teoria da arquitetura ocidental (isto é, da matriz européia de nossa

formação), escrito pelo arquiteto e engenheiro Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, que viveu no século

I d.C., e que faz parte do trabalho que intitulou De architectura (datado aproximadamente do

ano 40 d.C.). Este foi o único tratado europeu da antiguidade grego-romana que sobreviveu

até os dias de hoje, e constituiu-se numa fonte de enorme importância para os estudiosos,

sobretudo desde o chamado "Renascimento" (desde a herança grego-romana nas artes,

ciências, política, etc.). Sua redescoberta pelos arquitetos e teóricos da arquitetura

renascentistas deu vida ao classicismo dos períodos históricos subseqüentes – em toda a

Europa, e daí para o mundo, através de suas colônias. Os mais importantes tratados dos

mestres europeus sobre arquitetura, desde o século XV basearam-se nessa fonte,

inspiradora e perturbadora. Perturbadora porque muitos dos principais "nós" conceituais

da teoria classicista da arquitetura foram inaugurados justamente por Vitrúvio, desde sua

concepção dos padrões canônicos, da sua teoria das proporções, até (em especial) seus

princípios arquiteturais de utilitas, venustas e firmitas.

. Para nós interessa, aqui, sua primeira visão acerca dos conhecimentos que

qualificariam o arquiteto, em seu tempo. É desconcertante a amplidão das áreas das

ciências, das humanidades, das atividades administrativas e práticas que Vitrúvio coloca

como necessárias à formação do arquiteto – bem como sua atualidade, no que tange ao

caráter articulador de conhecimentos que até hoje imprimimos à estrutura de nossos cursos

de graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Espero que vocês apreciem e reconheçam algo

do por quê somos, até hoje, um tanto vitruvianos.

A linha aristotélica

. A Poética de Aristóteles

. A sobrevivência da Poética: de Horácio a

* A tragédia

A questão das origens

Aristóteles: Tragedia derivada del Ditirambo, Comedia derivada de los Himnos

Fálicos.

30

. A “superioridade”/ prestígio da tragédia

. As partes da tragédia:

El gran momento de la tragedia griega, su siglo de Oro, pues duró eso, un siglo, tiene lugar

en el siglo V a.C. Se supone que el primer gran autor habría sido Tespis, pero los datos

acerca de él son frágiles, así que avanzaré 60 años hasta llegar a Esquilo quien en 590 a.C.

habría logrado su primer gran éxito. No es todavía el momento de hablar de manera

extensa de ellos, pero sí mencionaré a modo de introducción que los tres grandes valedores

de la tragedia ática son, cronológicamente, Esquilo, Sófocles y Eurípides.

Pero antes de nada, detengámonos un momento en el género teatral denominado Tragedia:

ðqué es la tragedia? Según Aristóteles, es la imitación (mímesis) de una acción noble y

eminente, cuyos personajes actúan y no sólo se nos cuenta y que por medio de la piedad y

el temor realiza la purificación (catarsis) de tales pasiones. Quiero subrayar la palabra

imitación, acción, piedad, temor, purificación. Esos son las piedras angulares de la tragedia

griega. Como afirma Silvio D'Amico, su fin didáctico y político es innegable, ya que los

espectadores ven objetivamente fuera de sí las mismas tórridas pasiones que se agitan

dentro de ellos. Contemplándolas de forma objetiva, se liberan de ellas. [Alumnos: como

vemos el fin del teatro y del cine no es meramente divertir, no seamos ingenuos, ðquién no

se ha identificado con las peripecias de un personaje, ha aprendido resultados de acciones e

incluso ha experimentado sentimientos muy reales en las salas de un cine o de un teatro?].

Pero ojo, D'Amico nos advierte que la tragedia no era de consumo privado, formaba parte

de una trilogía (no cuento ahora el drama satírico) trágica que se llevaba a certamen, y la

catarsis sólo se producía después de la tercera.

Cuál era el desarrollo estructural de la tragedia?

- Prólogo: escena prelimina que incluso puede faltar.

- Párodos: o canto del coro que entra al ritmo de la danza.

- Episódios: los actos, que se separan unos de otros a través de un estásimo.

- Estásimos: cantos que el coro levanta en los intermedios mientras permanece en la

orchestra.

- Êxodo: canto coral de salida, o escena final.

Aristóteles estableció asimismo los elementos trágicos esenciales, que son 6 y que él

organiza jerárquicamente: fábula, caracteres, elocución, pensamiento, espectáculo, y

melopeia. Como vemos, para Aristóteles, la fábula, esto es, la trama, la organización de los

hechos, es lo más importante en opinión de nuestro filósofo. Y es que la estructura es para

él lo más importante. Incluso llegó a establecer una serie de condiciones para que la obra

pueda considerarse bien confeccionada: ha de tener un principio, un desarrollo y un fin; las

obras de terminar con un suceso que sirve a la idea que se quiere expresar; que no se pueda

eliminar un suceso sin que la totalidad se vea afectada; su extensión debe permitir su

completa rememoración; la acción debe tener lugar en una vuelta de sol.

Y vemos asimismo que la elocución, esto es, la forma, está por encima del pensamiento,

esto es, el fondo. Toda obra trágica de teatro helénico se configura a las denominada

"normas clásicas" por haber sido utilizadas, precisamente, en la Grecia Clásica. Estas

normas clásicas son: unidad de tiempo, unidad de acción, unidad de espacio.

31

En lo que respecta a los caracteres constituyen el segundo elemento en importancia, ya que

Aristóteles opina que si la acción debe ser verosímil, más aún han de serlo los personajes.

El poeta deberá mediante el diálogo y la acción trazar una línea de conducta verosímil.

Aquí dejaremos a Aristóteles, ya que otras afirmaciones de su Poética nos parecen más

dirigidas a regular las producciones de los epígonos de la gran tragedia ática, que a recoger

las características de ésta. El profesor Festugière, en La esencia de la tragedia griega, nos dice

que sólo existe una tragedia en el mundo: la que tiene lugar en Atenas, en el siglo V, y es

escrita por Esquilo, Sófocles y Eurípides. Nietzsche dijo que con éste se había originado la

decadencia de la tragedia. En opinión del pensador alemán, la tragedia sólo tenía sentido

como resultado de pulsiones estéticas divergentes, pero complementarias, relacionadas con

las fuerzas expresivas y las representativas de la naturaleza, con lo dionisíaco y lo apolíneo.

Nietzsche afirmó que Eurípides había hecho que los dioses abandonaran la escena; había

desvirtuado la esencia misma de lo trágico.

Festugière admite que ciertamente, la esencia de la tragedia es la exposición de la creencia

de que las catástrofes humanas están originadas en potencias sobrenaturales ocultas, en el

misterio. Esto es, su esencia es la fatalidad. Si se elimina la fatalidad, ya no hay verdadera

tragedia. ðPodríamos considerar a Eurípides un verdadero trágico? Dado que las tesis de

Festugière a mí me han convencido, adelantaré que sí, pero no es el momento ahora de

justificar tal afirmación. [Aquí, podría plantear a los alumnos: supuestamente la fe en Cristo

elimina la fatalidad, pero imaginemos a un trágico ateo, ðsería un verdadero trágico o

escribiría dramas burgueses? ðNo son pajas mentales todo esto? ðNo está por encima de

todo nuestro deseo de hallar una justificación a nuestras jodiendas? ðNo es la tragedia

humana la que da existencia a los dioses en lugar de ser los dioses la esencia de la tragedia?

ðNo acudimos a los dioses en la tragedia, mimetizando nuestros dioses extraliterarios?].

Hybris − Sentimento que conduz os heróis da tragédia à violação da ordem estabelecida

através de uma acção ou comportamento que se assume como um desafio aos poderes

instituídos (leis dos deuses, leis da cidade, leis da família, leis da natureza).

Pathos − Sofrimento, progressivo, do(s) protagonista(s), imposto pelo Destino (Anankê) e

executado pelas Parcas (Cloto, que presidia ao nascimento e sustinha o fuso na mão;

Láquesis, que fiava os dias da vida e os seus acontecimentos; Átropos, a mais velha das

três irmãs, que, com a sua tesoura fatal, cortava o fio da vida), como consequência da sua

ousadia.

Ágon − Conflito (a alma da tragédia) que decorre da hybris desencadeada pelo(s)

protagonista(s) e que se manifesta na luta contra os que zelam pela ordem estabelecida.

Anankê − É o Destino. Preside às Parcas e encontra-se acima dos próprios deuses, aos

quais não é permitido desobedecer-lhe.

Peripécia − Segundo Aristóteles, "Peripécia é a mutação dos sucessos no contrário".

Assim, poderemos considerar um acontecimento imprevisível que altera o normal rumo

dos acontecimentos da acção dramática, ao contrário do que a situação até então poderia

fazer esperar.

Anagnórise (Reconhecimento) − Segundo Aristóteles, "o reconhecimento, como indica o

próprio significado da palavra, é a passagem do ignorar ao conhecer, que se faz para a

amizade ou inimizade das personagens que estão destinadas para a dita ou a desdita."

32

Aristóteles acrescenta: "A mais bela de todas as formas de reconhecimento é a que se dá

juntamente com a peripécia, como, por exemplo, no Édipo." O reconhecimento pode ser a

constatação de acontecimentos acidentais, trágicos, mas, quase sempre, se traduz na

identificação de uma nova personagem, como acontece com a figura do Romeiro no Frei

Luís de Sousa.

Catástrofe − Desenlace trágico, que deve ser indiciado desde o início, uma vez que resulta

do conflito entre a hybris (desafio da personagem) e a anankê (destino), conflito que se

desenvolve num crescendo de sofrimento (pathos) até ao clímax (ponto culminante).

Segundo Aristóteles, a catástrofe " é uma acção perniciosa e dolorosa, como o são as mortes

em cena, as dores veementes, os ferimentos e mais casos semelhantes."

Katharsis (Catarse) − Purificação das emoções e paixões (idênticas às das personagens),

efeito que se pretende da tragédia, através do terror (phobos) e da piedade (eleos) que deve

provocar nos espectadores.

Esto viene a significar que una obra no debe sobrepasar un día (en los hechos que narra);

no debe tener acciones secundarias, sino una sola y principal; y un sólo espacio, es decir, el

escenario sólo puede representar un espacio físico concreto (un palacio, o un jardín...) pero

nunca varios (no se permite convertir el escenario, por ejemplo, de los exteriores de un

palacio, a los interiores).

. Hegel e a dissolução da Tragédia

. A tragédia torna-se História

. EX: Domenach «Metamorfoses da tragédia”

. O trágico em Nietzsche

. A vida só é suportável pelo sonho (Apolo) ou embriaguez (Dioniso)

. A esteticização da vida e a tragédia da história

. A modernidade e a dialéctica do trágico: a tradição do retorno

. A centralidade da tragédia na tradição teatral antiga e moderna

. História e autoria:

a) Tragédias e comédias do Renascimento Português

Autores de ‘transição’:

. Anrique da Mota

. Gil Vicente

b) O teatro neolatino

Alguns autores nacionais

. Camões

. J. F. Vasconcelos

. António Ferreira

c) O teatro neo-clássico/iluminista: introdução

Teorização

Autores:

Cruz e Silva

Correia Garção

33

Manuel de Figueiredo

34

* A comédia

. Menos teorizada

. Oposição relativamente ao trágico

El término Comedia provendría del griego "comos" que no es ni más ni menos que

aquellas injurias y dichos que el pueblo griego lanzaría en las fiestas dionisíacas como

elemento satírico y humorístico. La comedia es, ante todo y sobre todo, una crítica

endulzada con el humor que gustosamente tomaba el público griego poco después de

haber visto representarse las tragedias en los concursos.

En la tragedia, el espectador sabía qué es lo que iba a ver, conocía el tema, sin embargo, en

la comedia, el argumento se ignora totalmente: se encuentra el espectador ante una trama

desconocida y unos personajes también desconocidos. El comediógrafo tiene que llevar a

cabo una gran labor creadora y debe ser original. Todo es materia para la temática de la

comedia, pero sobre todo, temas cotidianos, de la misma calle y del mismo tiempo en que

los espectadores vivían, así vemos que, Aristófanes llevará a escena la política de la

época, las innovaciones de la Atenas que le es contemporánea, la filosofía, las nuevas ideas

sobre la educación de la juventud (sofistas), coge a los mismos personajes que pasean por el

ágora y los caricaturiza y satiriza. ¡El mismo Sócrates aparecerá ridiculizado por Aristófanes

La vida cotidiana es un espectáculo cómico, es el hecho de reírse "de uno mismo".

Con todo esto, la tragedia no es un retrato "realista", ni mucho menos, los temas y los

personajes son reales (o al menos tomados de la realidad) pero la trama resulta a veces

inverosímil y disparatada, casi rozando lo absurdo. Es una explosiva mezcla de

realidad y la fantasía más disparatada. Para Aristófanes la risa es un fin, así que todo tiene

cabida en su teatro. La comedia es un desahogo de alegría, de hecho, filósofos de

épocas anteriores habían definido al hombre como el único ser capaz de reír.

La comedia, que cuenta con una alternancia entre coro y personajes parecida a la de la

tragedia, se diferencia, principalmente de ésta en dos puntos:

Agón o combate. Es el primer episodio de la comedia en el que hay una lucha en la cual, el

vencedor, es el personaje que representa las ideas del comediógrafo. Disputa e triunfo de

um actor que assume as ideias do poeta, distanciação e metateatro;

Parábasis: o coro muda de função (não se dirige a personagens fictícias), interpreta o

espectáculo e dirige-se ao público. O recurso à parábase nas comédias de Aristófanes é

frequente. N'Os Pássaros, por exemplo, o coro ameaça a audiência, caso esta não lhe atribua

o primeiro prémio. Durante un momento de la representación cuando la escena ha

quedado vacía y los actores han salido, el coro se quita sus máscaras y mantos y avanza

hacia el público. Esta parábasis tiene siete partes, a saber: Commation: un canto muy breve

Anapestos: discursos al público lanzados por el corifeo (dirigente del coro); Pnigos: es un

parlamento largo sin interrupción; Cuatro trozos de estructura estrófica.

. O Tratactus Coislinianus (séc- X)

. A teatralidade da comédia (enfatiza o conceito de “espectáculo” em Aristótles)

. A incongruência: cómico # princípio do real

. Personagens médios, ambientes cotidianos e linguagem informal;

35

Excurso:

. «A comédia», de Gilles Girard et. al., in Universos do Teatro, almedian, Coimbra

. Uma tradição com vários momentos:

. comédia grega

. comédia latina

. comédia medieval

. comédia burguesa

. etc.

Excurso:

. Lo comico y la regla» de U. Eco, in La estrutura de la ilusion, Barcelona, Lumen, 1986, pp.

368-78.

Excurso: Mandrágora

Encenação: Ricardo Pais

Actores: António Jorge, Carlos Borges, Carlos Gomes, Carlos Sousa, Isabel Leitão, José

Neves, José Vaz Simão, Rosário Romão e Sílvia Brito

“Maquiavel e o Teatro”, por Rita Marnoto

- Que nenhum homem com menos de trinta anos possa pertencer à dita companhia; as

mulheres podem ter qualquer idade.

- Que a dita companhia tenha um chefe, homem ou mulher que seja, durante oito dias; háde ser primeiro chefe, dos homens, pela devida ordem, o que tiver o nariz maior, e das

mulheres a que tiver, pela devida ordem, o pé mais pequeno.

- Quem não criticar, durante um dia, o que se fizer na dita companhia, homem ou mulher

que seja, será punido do seguinte modo: se fôr mulher, devem-se pendurar as suas chinelas

num sítio onde toda a gente as veja; se fôr homem, penduram-se as suas calças do avesso,

num lugar alto, visto por todos.

- Que digam sempre mal uns dos outros; e dos de fora que lá venham parar, dizer todos os

seus pecados, e dizê-los em público, sem nenhum respeito.

- Que ninguém da dita companhia, homem ou mulher, se confesse noutra ocasião que não

seja a Semana Santa; e quem desobedecer seja obrigado, se é mulher, a carregar, e se é

homem a ser carregado, pelo chefe da companhia como ele bem entender, para confessor

deve escolher-se um cego; se for surdo tanto melhor.

- Que ninguém possa nunca, em qualquer circunstância, dizer bem de outrem; e se alguém

desobedecer, seja punido da mesma maneira.

Nicolau Maquiavel,

(Capítulos Para Uma Companhia de Divertimento,

Tutte le Opera, Firenze, 1971)

Como nasce o Maquiavel homem de teatro? Apesar de esta ser uma faceta da sua

personalidade pouco conhecida, Maquiavel é, por essência, um homem de teatro que não

esperou pelo ano de 1518 para o revelar. Quando, restaurado o poder dos Médicis, o

funcionário da república foi forçado ao exílio, o ócio de S. Casciano, onde escreve a

Mandrágora, apenas lhe oferece a oportunidade de pôr de pé projectos literários que há

muito vinha matutando. O prólogo desta comédia poderia ser, aliás, o prólogo e o epílogo

36

de toda a sua vida. Nele se reflecte uma concepção amarga da existência e uma vontade de

domínio assente na perfeita consciência do que é o espectáculo ou o engano.

Ainda muito jovem, além de traduzir Andria de Terêncio, compõe uma peça, hoje perdida,

intitulada La Maschere, que se supõe inspirada em Aristófanes, e, nos últimos anos de vida,

escreve ainda uma outra comédia, Clizia. Mas os seus escritos políticos dão mostras de uma

vivacidade narrativa a que subjaz a facilidade com que interpreta gestos e movimentos de

actores que trabalham sobre um palco. No Diálogo intorno alla nostra lingua, entrevista o

próprio Dante, que dá as devidas explicações sobre as suas opções estilísticas. O tratado

Dell'arte della guerra, por sua vez, é escrito sob a forma de diálogo. São muitas as cartas em

que, ao responder a amigos, começa por fazer a reconstituição dramatizada da situação que

lhe havia sido apresentada, para depois a comentar. Ao diplomata que trabalhou para o

governo da república, para os Médicis, ou para o papado, será dado conhecer como a

poucos dramaturgos do século XVI a arte da representação e da dissimulação, a máscara do

anjo ou do Diabo. Tanto nos seus escritos políticos, como na sua actividade profissional,

ele é o encenador que, depois de ter dado as devidas instruções às personagens que põe em

cena, as deixa agir aos olhos do público.

Se Maquiavel sabe bem que o sucesso do espectáculo de corte é indissociável, no seu

tempo, da imitação da espectacularidade dos antigos, a sua vasta cultura oferece-lhe um

bom conhecimento do teatro dos clássicos. A estrutura da Mandrágora segue de perto a

regra aristotélica das três unidades, e da boca das suas personagens saem, a cada momento,

expressões que encontram a sua correspondente em Andria. Esta comédia distingue-se,

porém, dos seus antecedentes mais directos, o Formione (1506), a Cassaria (1513), por um

maior desprendimento em relação às convenções do género, o que é indissociável do lugar

ocupado pela tradição dramática florentina no âmbito da produção teatral de Maquiavel.

Os empréstimos de Andria são adaptados às inflexões do falar de Florença. A unidade de

acção é enfatizada pela complexidade da sintaxe da intriga, dotada de um ritmo rapidíssimo

que em nada afecta o seu perfeito geometrismo. A unidade de tempo, lugar e acção é

reforçada pela função agregadora de que se revestem os intermezzi cantados entre cada

acto, onde são inseridas figuras que pagam o seu tributo ao idilismo do imaginário

renascentista, jovens e ninfas. Desta feita, porém, não é propriamente um quadro de

harmonia perfeita, semelhante ao simbolizado pelas ninfas de Botticelli, que esta " brigata"

vem apresentar. Nos versos que canta, acumulam-se tópicos stilnovistas e petrarquistas,

mas o amor de Calímaco é uma paixão bem diferente, desenfreada, que quer ver o desejo

satisfeito a todo o custo.

A tradição do teatro florentino era tão familiar a Maquiavel, que ele mesmo escreveu os

estatutos de uma "compagnia", dos quais foi transcrito um excerto. Apesar de o seu texto

não ter sido acabado, bem poderia tratar-se da paródia dos regulamentos de uma dessas

associações festivas. A Mandrágora termina com um ofício matinal, mas Frei Timóteo

dispensa a alegre companhia das "laudes", para que os "anti-laudesi" vão saciar a fome do

corpo. Particularmente contundentes são as críticas desferidas contra o materialismo e falta

de ética do clero, simbolizados por Frei Timóteo, e contra a estultícia dos homens de leis,

representada pelo Doutor Nícias, quando enquadradas no clima de uma comédia clássica.

Mas se atentarmos na abertura do "Canto dei diavoli" entoado por um grupo de diabos que

coroa um carro triunfal onde vão Plutão e Proserpina, poderemos compreender melhor a

acerbidade do secretário florentino:

Já fomos, agora já não somos ,

Espíritos beatos;

37

pela soberba nossa,

fomos todos do céu expulsos;

e desta cidade vossa

tomámos o governo, pois aqui se mostra

confissão e dor mais que no inferno

(Tutte le Opere, pag. 988)

Maquiavel sempre se manteve distanciado dos círculos neoplatónicos, bem como das suas

tendências orientalistas e ocultistas. O homem de Renascimento é mais fascinado pela

imagem de um império romano feito força e acção, do que por um helenismo

espiritualizante. No Príncipe, faz a apologia do centauro, metade inteligência humana,

metade astúcia animal. Na comédia, a mandrágora é a planta que fascina pelo que tem de

misterioso e de maléfico, sem que nunca seja efectivamente utilizada, valendo apenas como

arma de persuasão. A troca, o disfarce, ou a máscara, revestem-se de um sentido

absolutamente perverso, o que os aproxima mais de um jogo de máscaras carnavalesco, do

que dos fáceis efeitos de troca de identidades de uma dupla de personagens, estereótipo

que toda a comédia, a partir do séc. XVI, há-de repetir até à saciedade. É que a

mandrágora, tal como os diabos das festas renascentistas que atacam os peregrinos, ou

como a coca-cola, cuja fórmula secreta é a alma do negócio, fundamentam a sua força de

atracção no mistério que os envolve. Por isso, se, no prólogo, quando se diz que a cena

podia passar-se em Florença, Roma ou Pisa, se prevê a adaptação da representação a outras

cidades, também o texto se abre à representação noutros tempos e de outros tempos. O

abstracionismo figurativo da rampa, da mesma feita pódium e esconderijo, pode então

levar para além do proscénio o Siro a que Ricardo Pais deu um game-boy, ou o Nícias a

quem deu um chapéu de coco.

38

* A tragicomédia

. O termo tem origem no Anfitrião de Plauto.

. Desenvolve-se mais consistentemente a partir do século XVI e até séc. XVIII, quando

aparecem termos concorrentes: tragédia cómica, comédia séria, comédie larmoyante, drama

etc.

. O conceito põe em causa o temor clássico perante as misturas de géneros,

. O cristianismo foi o primeiro a pôr em causa o fim trágico, pois a Paixão origina a

felicidade;

. Aparecimento de textos híbridos como:

. La Celestina. A partir da edição 1502 designa-se: Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea

nuevamente revista y emendada con addición de los argumentos de cada un auto en principio. La qual

contiene demás de su agradable y dulce estilo muchas sentencias filosofales y avisos muy

necessarios para mancebos mostrándoles los engaños que están encerrados en sirvientes y

alcahuetas. Texto de Fernando de Rojas.

. Pastor fido (1590) de Guarani, tb. contrasta o destino trágico das figuras com o

espaço campestre;

. El arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609) de Lope de Vega é um dos textos

teóricos que cuestiona das divisões aristotélicas. El dramaturgo amaba la vida y concebía el

teatro como una manera de representarla, por ello mezcló la comedia con la tragedia, lo

aristocrático y lo plebeyo, lo divino y lo humano. Para captar la atención del público trata

temas heróicos, religiosos, pastoriles, de costumbres y utiliza personajes representativos de

la sociedad española del siglo XVI, portadores de cualidades genéricas humanas (el joven,

el viejo, la dama, el gracioso, la criada ...) Asimismo acomoda sus versos a los temas,

usando toda clase de rimas métricas. Lope de Vega se inspiraba en la historia, la literatura,

las vidas de los santos, el mundo fantástico y su vida y experiencia personal para redactar

sus obras de teatro.

. Le Cid (1638), que Corneille designa como tragedia com final feliz

. King Lear (1605) de Shakespeare

. A comédie larmoyante concorre com o género a partir de XVIII: comédia que suscita

lágrimas em lugar de riso.

. Sobrevivência da tragicomédia em Chekov e Valle Inclán (Esperpentos), e em autores

relacionáveis com o absurdo, como Dürrenmatt ou Ionesco.

. Definição: mistura figuras, espaços e enredos das tradições cómicas e trágicas. Mistura até

o verso e a prosa. Contra o precieto ciceroniano: «et in tragedia comicum vitiosum est et in

comoedia turpe tragicum…»; a tragicomédia enfatiza a convertibilidade entre o trágico e o

cómico: algo que começa como cómico pode redundar em trágico (cf. Teatro absurdo)

ex: A Cantora Careca de Ionesco situa-se neste ponto intermédio